Iosepa, Utah. Though it now stands abandoned at the base of the Rocky Mountains, it was once a thriving town—a Hawaiian colony in the desert where settlers spoke their native language and maintained their culture. One of its early inhabitants was an LDS convert from Hawaii named Makaopiopio. Raised in an oral society, Makaopiopio’s history was recorded by author Marianne Monson, as it was shared with her by those who knew Makaopiopio.

In 1850, missionaries from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints arrived in the islands. Initially, they planned to proselytize only among the haole (white) inhabitants since none of the missionaries spoke Hawaiian, but they did not receive a warm welcome: already existing Christian groups protested new competition, sailors showed little interest, and the Hawaiian government refused to grant permission for the group to publicly gather. Many of the missionaries became discouraged and decided to head back to the states. A few, however, including George Q. Cannon and Joseph F. Smith, decided to learn Hawaiian and preach to the native population. Surprisingly, they began to have success. Makaopiopio’s husband was baptized in 1854, and records indicate that Makaopiopio joined him in 1862. The delay may have been due to opposition from her family or perhaps her own reluctance to convert again.

Photo of Hukilau Beach from Getty Images

Makaopiopio and her husband purchased land near several other members of the Church in Laie, on the north shore of Oahu, where they worked on a Church-owned ranch, growing cotton, coffee, potatoes, and taro. A beautiful and vibrant community developed in the area, encompassed by lush green mountains on one side and the sparkling waves of Hukilau Bay on the other. Makaopiopio raised her children in Laie, sending them to a school established by Latter-day Saint missionaries.

► You'll also like: 5 Ways the Church Is More Fun in Hawaii

About this time, one of the earliest LDS converts and most prominent Hawaiian leaders, Joseph Napela, visited Salt Lake City and returned to Laie with a positive report about the city. Though other Hawaiians hoped to visit Utah and possibly settle there, King Kamehameha IV watched the declining native population with alarm and did not want to lose more of his people to emigration, so he forbade the practice with few exceptions.

Makaopiopio’s daughter Likabeka grew up with a young man named J.W. Kaulainamoku in Laie. In his teens, J.W. became close friends with one of the LDS missionaries from Utah, who invited J.W. to return to Utah with him at the conclusion of his mission. The King granted permission, and J.W. worked as a stonecutter on the Salt Lake Temple. Though Likabeka was a teenager when he left, a few years later, J.W. wrote requesting her hand in marriage, and Likabeka accepted. Joyfully, Makaopiopio and her husband planned to accompany their daughter to Utah for the wedding.

Photo from Wikimedia Commons

On the day they planned to sail, however, Makaopiopio and her husband arrived at the ship, only to learn that they had been denied passage. The reasons for the last-minute reversal are unclear, but it must have been discouraging for Makaopiopio to send her daughter off without the support of her parents. Fortunately, a close friend from Laie agreed to accompany Likabeka, which comforted Makaopiopio, though it hardly compensated for missing her daughter’s wedding. Likabeka and J.W. were married in Salt Lake City in 1876.

A short five months after her husband’s death in 1879, Makaopiopio, now in her sixties, sailed for San Francisco and traveled overland through the frigid Sierra Nevadas to Utah, arriving at Christmastime. Deeply grieving the loss of her husband, Makaopiopio’s journey was motivated in part by a desire to reunite with her family and to visit the LDS temple. She received a joyful welcome from her daughters and son-in-law after the family’s long separation.

Seven years after Makaopiopio’s arrival, however, her daughter Likabeka passed away from the dreaded disease leprosy.

► You'll also like: Mormons, Leprosy, and the Remarkable Story of Kalaupapa

Though leprosy is curable today, it was a malady frequently associated with the Hawaiian islands, which only increased prejudice against Polynesian immigrants. Leprosy arrived in the islands in the 1830s, most certainly carried on ships from Europe, where it was fairly common; the prevalence of the disease led to the creation of the leper colony on the island of Molokai. The highly feared illness took years to manifest, and the method of contagion remained a mystery.

Ostracism from the surrounding community must have been difficult, as several local newspapers carried notice of Likabeka’s progressing illness. After Likabeka’s death, Makaopiopio stayed close to Maria, her grandchildren, and sons-in-law, as well as a network of extended family members and friends. Concerned about the community, religious leaders broached the possibility of starting a separate Hawaiian colony, like many of the other LDS satellite colonies established around the western United States and Canada.

The Hawaiian community responded positively, and they chose leaders, including J.W., to identify possible sites. In 1889, the LDS Church purchased 1,920 acres, and the Hawaiian Saints named their settlement Iosepa, which is Hawaiian for Joseph, in honor of Joseph F. Smith, their beloved missionary.

J.W. built one of the first homes, separated from the rest of the community because Makaopiopio had now become ill with the same disease that had taken her daughter. Over time, the Hawaiian Saints would build houses, a general store, a school, a chapel, fire hydrants, and an irrigation system. They would cultivate crops, plant trees, raise livestock, and even experiment with growing seaweed.

Though they often adopted new practices, many of the traditional ways remained. Records note the marketing of flower leis and poi bowls, and Hawaiian remained the dominant language, though English was commonly spoken as well. Settlers created their own currency usable at the town store, and nearly all contemporary sources comment on the beauty of streets lined with poplar trees and yellow rose bushes. Makaopiopio, however, would not live to see these developments. Three weeks after her arrival, she succumbed to leprosy, becoming the first settler to die in Iosepa colony. Her death necessitated the choosing of a burial site, and community members selected a secluded area to serve as a graveyard. Here she was laid to rest, mourned by family and friends both nearby and an ocean away. Though her gravesite was marked, the headstone may have been made from wood or other delicate material. A few years later, a brush fire destroyed many of the markers in the cemetery, and today the exact location of her grave remains unknown. J.W. was also buried there.

Photo from Wikimedia Commons

The Iosepa colony would continue for another twenty-eight years until Joseph F. Smith announced a temple would be built in Laie, at which time a few families withdrew to Salt Lake City, while most chose to return to the islands. Returning pioneers built homes on a street in Laie designated in their honor—to this day it is named Iosepa Street. The buildings and cultivation efforts in Iosepa, Utah, crumbled with passing years and returned to the earth. At this time, you can find remaining brick foundations and the cemetery with a memorial to the Hawaiian settlers. A separate monument honors Makaopiopio, the first one laid to rest there.

Her descendants in Laie explain that she is their beloved tutu (grandparent) and that part of her legacy was her choice to always go forward. On the marker they erected in Iosepa, they wrote: “from the highlands of Waimea, to the brackish lowlands of Laie, up to the Rockies of Utah, and finally, to the desolation of Iosepa. Blessed by the voyages of her faith, we . . . pay honor and tribute to tutu Makaopiopio.”

Every Memorial Day, the ghost town of Iosepa comes to life as descendants of settlers from the islands and the valley gather for a luau celebration. With speeches, music, dance, and food, Iosepa lives again, evidence of the legacy that connects a ghost town on Utah’s frontier with the islands of Hawaii. I wish Makaopiopio could see the integrated cultures paying tribute to her stalwart journey, to her ability to navigate enormous changes, and to the fascinating events underlying her life.

Lead image from billiongraves.com

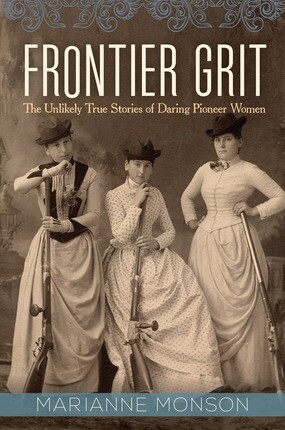

For more fascinating stories about pioneer women in Church history, check out Marianne Monson's Frontier Grit: The Unlikely True Stories of Daring Pioneer Women, available at Deseret Book stores and deseretbook.com.