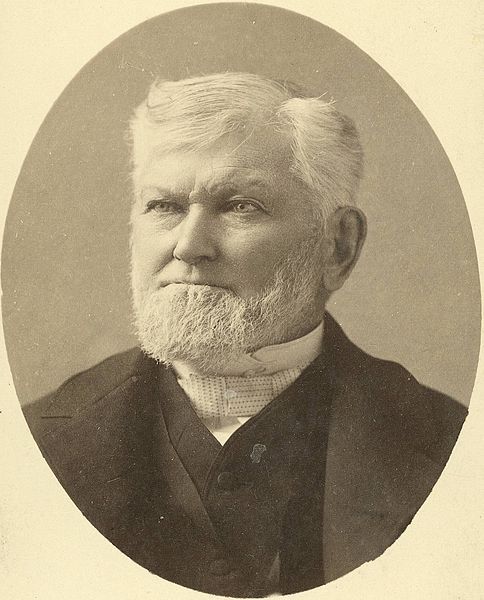

Many Mormons are familiar with the story of how then-apostle Wilford Woodruff had a vision of the Founding Fathers in the St. George Temple and how they asked him to do their temple work. Some Mormons may also be vaguely aware that when Woodruff did the Founding Fathers' work that he also performed the ordinances for about 45 “other eminent men” from history.

Few, however, know that for more than a century, there were a few historical mysteries in the story of Woodruff’s vision—missing eminent men and women hiding in the events surrounding what Woodruff was inspired to do in St. George, Utah.

The Vision

In August 1877, Woodruff had what he called two “night visions,” a scriptural way of describing dreams. But these were more than just ordinary dreams—he recognized them as inspired visions. The experience was so vivid that he spoke about them as if they were visits. In them, he said, the Signers of the Declaration of Independence gathered around him and “demanded” and “argued” that he get their temple work completed. He later said George Washington was also present in that request.

“You have had the use of the Endowment House for a number of years,” the Signers said to him, “and yet nothing has ever been done for us.”

In other words, the sticking point in this accusation wasn’t baptisms for the dead, but endowments—the higher temple ordinances.

In fact, the proxy baptisms for the Signers had been completed in stages by various people starting in Nauvoo and ending in 1876. John D. T. McAllister, who helped Woodruff in the temple, had even participated in doing some of the Signers’ work six years earlier.

Even though there were no temples in Utah until the 1877 dedication of the St. George Temple, members of the Church were able to have their own, live endowments in the temporary “Endowment House” on Temple Square in Salt Lake City. Endowments for the dead were only first performed in St. George beginning on Jan. 11, 1877.

By August 1877, endowments for the dead had been going on for months, yet nothing had been done to complete the Signers’ temple work. Woodruff determined to do it himself.

A Hundred Men

Woodruff discovered that all of the temple work for Signers John Hancock and William Floyd had already been performed in the St. George Temple prior to the vision. This left 54 Signers who still needed to have their temple endowments completed.

He decided he would inaugurate their temple work by redoing their baptisms. (It was standard practice at the time for people to be re-baptized before they went through the temple for their endowments.) He also decided that he would choose 46 other men to make it an even 100.

The plan was to have McAllister baptize Woodruff for the 100 men. Then Woodruff would baptize McAllister for Washington, Washington’s relatives, and other deceased presidents of the United States. McAllister then would baptize Lucy Bigelow Young for 70 eminent women.

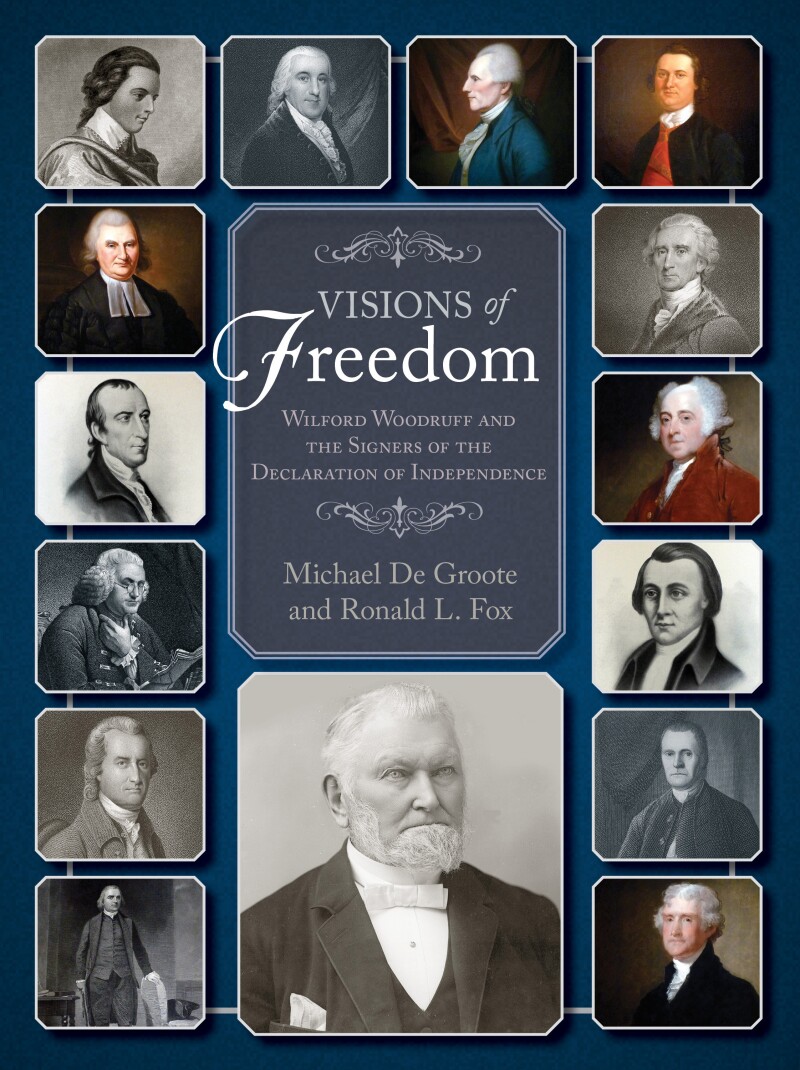

Learn more about this fascinating piece of Church history in Visions of Freedom: Wilford Woodruff and the Signers of the Declaration of Independence

Visions of Freedom will bring readers face-to-face with the signers of the Declaration of Independence, where they can look at the lives of the eminent men and remember not just the things they achieved in life but also their final request for true freedom as they came to a sleeping Apostle in a white temple among red rocks.

-->Get your copy of Visions of Freedom now

Eminent Men and Women

Woodruff was very clear in his accounts of the vision that only the Signers and Washington appeared to him. To find the extra 46 men, Woodruff turned to a set of books titled Portrait Gallery of Eminent Men and Women of Europe and America by Evert A. Duyckinck. The popular two-volume set was a compilation of biographies of famous people.

With only a few exceptions, Woodruff took the names of the 46 from these books. The biographies are in the same non-alphabetical order in the books as they are in his listing of names in his journal. Most of the eminent women are also either in the books under their own biographies or are wives of those men he copied from the books. Christopher Columbus and John Wesley are two examples, however, of the few names that he chose not from these books.

The Missing Man

Scholars have scratched their heads over Woodruff saying he was baptized for 100 men, because his journal listed only 99. Some have searched the St. George Temple records to see if there was another famous man baptized around that same time. Others saw that he had crossed out one name he had written twice, Francis Lightfoot Lee, and assumed he had just counted Lee twice. Others thought he just miscounted.

And even though a whole book was written on the eminent men and other researchers and historians have looked closely at Woodruff’s journal, the mystery of the 99 eminent men and the missing man remained.

The solution, however, was quite simple. The popular published version of Woodruff’s journal made a transcription error—missing one person.

The result was that the man who ran the first commercially successful steamboat, Robert Fulton, was omitted from the journal transcript. Woodruff didn’t make a mistake. The 100 men he was baptized for were all written and accounted for in his own handwriting in his original journal.

Skipping Other Men and Women

Woodruff most likely knew when he was browsing through the biographies that he had more than 46 eminent people to choose from. As he skimmed the names, he had to make choices. Inevitably, he had to skip some names.

Some of the names he skipped over, for whatever reason, were Edmund Burke, Napoleon Bonaparte, William Wilberforce, Thomas Moore, Samuel Morse, Charles Dickens, and Robert E. Lee. Other names he skipped, such as Benjamin Disraeli, Florence Nightingale, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow were logical to pass over since they were still alive in 1877.

The Missing Wife

Woodruff’s vision of the Signers and his own inauguration of the temple work for them and the other eminent men has also overshadowed the fact that he prepared a list of eminent women as well, including people such as Marie Antoinette, Jane Austen, Dolley Madison, and Charlotte Bronte.

However, one of the eminent women Woodruff compiled was a mistake. After he chose Benito Juárez for one of the 100 men, he skimmed Juárez’s biography for his wife’s name. On page 125, he saw the phrase, “He had been for some years married to the Princess Charlotte, daughter of King Leopold of Belgium” and assumed this was Juárez’s wife.

She was not.

The paragraph was about Juárez’s enemy, Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico. Princess Charlotte was Maximilian’s wife and went by the name “Carlota of Mexico.”

Princess Charlotte died in 1927, and since she was alive in 1877, she was a poor candidate for proxy temple work.

Juárez’s real wife was Margarita Maza Juárez, whose temple work was done correctly in the Salt Lake Temple in 1921.

An expanding scope

The visit of the Signers to Woodruff began a process of changing the way Latter-day Saints thought about the scope of temple work. Not only did they begin to understand the necessity of performing all ordinances of the gospel for those who were dead, but also they began to see that the temple and its ordinances were meant for all people.

Today, the Church strongly discourages Mormons from doing similar "celebrity" baptisms, but the legacy of Woodruff’s experiences shows the importance of reaching out to all God’s children.

Visions of Freedom: Wilford Woodruff and the Signers of the Declaration of Independenceis by former Deseret News journalist Michael De Groote and photo historian Ronald L. Fox. It is available at Deseret Book in paperback, e-book, and audio book. The book examines Woodruff’s vision and its impact on temple attitudes and practice and includes appendixes of all known accounts of his vision—including a possible forgery. The bulk of the book features biographies for each of the 56 Signers of the Declaration of Independence.