I was in England when President Monson called me on the phone and asked me to write his biography. It was June 18, 2008, a Thursday, and the experience is forever imprinted in my heart and mind.

“I know you’re on a mission,” President Monson said. “I called you. But you’re not that busy, are you? I have decided I want you to write my biography.” He suggested I could get a good start on the biography and be halfway done before coming home the next year.

How do you write about the life of a prophet? “Daunting” is a good word to describe the task. Overwhelming. All-consuming. Humbling. So humbling to realize, in some ways, his life was in my hands. I read, researched, outlined, and pondered what I would write, and it was almost like any other project of putting words on a page. Yet there came a spiritual dimension like no other writing project, a sensitivity that was a constant reminder of whose work I was doing.

I never imagined what would come from that preparation.

The following video was filmed at a Time Out for Women eventand shows Heidi S. Swinton sharing lessons learned and memories shared while writing President Monson's biography:

Starting Out

After that momentous call, I devoted six hours a day to studying President Monson while maintaining a full schedule of teaching with the missionaries, accompanying my husband to meetings, and speaking at conferences and trainings. I read all of President Monson’s talks from 1963 to 2010—that took months.

I studied materials relating to President Monson’s life—the pioneer church in Scotland and Sweden, the Depression, World War II and its aftermath, life in Germany behind the Iron Curtain. I read his limited-edition autobiography from 1985 and studied family records sent from his office. I read the biographies of every prophet of the Church. I interviewed European leaders who worked with him and members who were touched by his service. I read the scriptures, particularly the four gospels recording the ministry of the Master.

The most significant contributions to my research were probably regular video conferences with President Monson. I discovered President Monson’s philosophy on love and service during that time. I loved those hours with him. He was open and candid, thoughtful and dignified, cheerful and charming. Our conversations were not fact and date driven. Rather, he shared personal accounts, which are more than just stories.

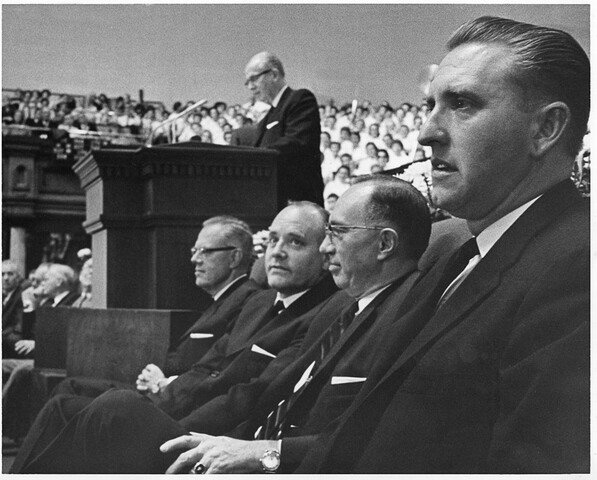

He talked of his childhood and his family, of his call as an Apostle and his treasured experiences with mentors like J. Reuben Clark, Harold B. Lee, and Mark E. Peterson. He spoke of committees and travels and the people he met in remote Australian airports and behind the Iron Curtain in East Germany. I was mesmerized by everything he said.

Most importantly, I learned that he doesn’t measure his life in momentous events but in memories of people—and what he learned from them.

As I wrote about his life, as I reviewed the scores of personal accounts that reflect his great heart and sincere soul, I found I was changing. Put simply, I wanted to be better.

The German Connection

Suddenly it came time for my husband, Jeff, and I to complete our assignment in England and go home. Before returning to the states, we made an important stop in Germany so that we could walk the ground and meet the people who had played such an important part in President Monson’s 20 years of supervising the Church behind the Iron Curtain. To understand the ministry of this leader, I needed to meet those remarkable Saints sequestered behind the Wall who had worked so closely with him. Hearty priesthood holders wept as they expressed their profound love for President Monson.

While attending church services in Görlitz at the dilapidated factory-turned-chapel, I imagined the huddled Saints and their surprise when the young, bold Elder Monson stood at the podium and promised them that all the blessings that the Lord had for his children would be theirs. The East Germans never forgot the promise, and for two decades, under the direction of the First Presidency, he carefully helped fulfill those promises. Jeff and I took the opportunity to stand on the overlook above the Elbe River where President Monson had blessed the communist country that there would be “the dawning of a new beginning” of the Lord’s work in the land—another promise that would find joyous fulfillment on June 29, 1985, when a temple was dedicated in Freiberg, Germany, behind the Iron Curtain. President Monson described the day as a “highlight in his life.” Not long after, the Berlin Wall came down. The members of the Eastern Bloc countries had indeed witnessed great drama as the blessings of the kingdom of God came to them.

The Home Stretch

When I came home to Utah from the mission, I read all of President Monson’s journals. The volumes, kept since 1963, are letter size, single spaced, with almost-daily entries. His journals sometimes indicate what happened in the Appropriations Committee or the Board of Education Committee, the Missionary Committee or the Correlation Committee—all of which he chaired. But for the most part, President Monson’s notes are filled with his interactions with people. He frequently acknowledges the work and efforts of so many, those whose service, as he says, “often goes unthanked and unacknowledged.”

When I sat at a desk in his outer office reading and making notes, he would regularly pass by with a box of chocolates, select one for me, set it down, and with a twinkle in his eye say, “Be nice to me.”

I spent the next year researching, reviewing, and writing, writing, writing.

During all this time I found a consistency to President Monson’s life—he loves people. He shows that love at the conclusion of a meeting when he makes time to talk with people; he extends that love when he visits, gives blessings, pursues someone who has fallen away or just smiles to a crowd, and each person feels that smile is just for them. I worked tirelessly to adequately reflect that love throughout his biography.

A Prophet for All

Mention President Monson’s name in a gathering—Church or community—and people line up to tell their stories about him. He has left an imprint in every home, ward, state, and nation he has visited. There are too many stories to even record.

The Canadians think he is “theirs” and so do the East Germans and the Pacific Islanders and the Australians. Essentially he has made lasting friends everywhere he has gone, and even where he has not.

I have watched as he reached out to those in the community, heads of state, ambassadors and political leaders with the same trademark familiarity. He has joined many community leaders of various faiths in helping with community causes. I love the story of him watching the news one night when the announcement was made that the shelves of a local food bank were nearly bare. He acted immediately, calling the Presiding Bishop and suggesting it was time to rotate some of the food stuffs at Welfare Square and send the supply to the food bank for the needy.

When he says to find “joy in the journey,” he is not suggesting a day at an amusement park or a quiet afternoon with a good book, (though he does read every evening, often a book from the era of World War II). “Joy in the journey” is found in lifting the burden of another, he says. He puts in this way: “To measure the goodness of life by its delights and pleasures and safety is to apply a false standard. The abundant life does not consist of a glut of luxury. It does not make itself content with commercially produced pleasure, the night club idea of what is a good time, mistaking it for joy and happiness.” His standards of an abundant life are rigorous: obedience to law, respect for others, mastery of self, and joy in service of the Lord.

We can all live up to that standard. A prophet of God has called us to it. And, in doing so, there is no question, we will be better.

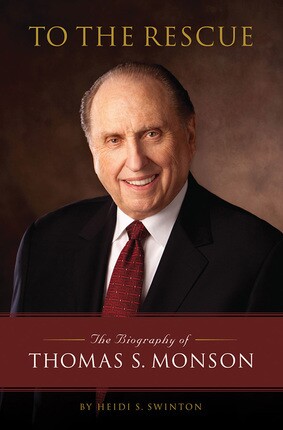

To the Rescue chronicles the life and ministry of our beloved prophet President Thomas S. Monson. It is filled with the heartwarming personal accounts so typical of him— some that have become favorites over time and many others that have not been told before. Readers will be transported to his childhood, where he learned his first lessons about reaching out to others. They will glimpse his school experiences, his hobbies (especially his prize Birmingham roller pigeons), his military service in the navy, and his courtship with Frances Johnson, who would become his eternal companion and greatest support.

Most important, readers will observe Thomas S. Monson going “to the rescue” in his decades of devoted Church service. Called as a bishop at age twenty-two, as a counselor in a stake presidency at age twenty-seven, as a mission president at age thirty-one, and as a member of a Quorum of the Twelve Apostles at age thirty-six, he became early on a skilled administrator and a tireless servant of the Lord. He oversaw the work of the Church in East Germany for more than twenty years, beginning with hushed meetings held in automobiles to avoid listening devices and culminating in the dedication of a temple behind the Iron Curtain. He played key roles in landmark programs in the Church, from correlation to welfare to the publication of the LDS editions of the scriptures. And through it all, he recognized people as individuals and ministered to their need in personal ways.