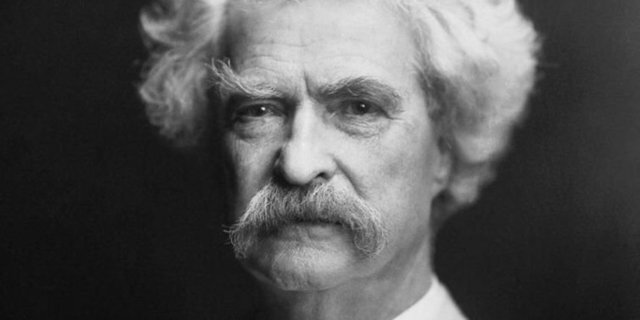

Mark Twain—author of popular classics like The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn—was celebrated in his New York Time obituary as the “greatest American humorist of his age.”

On June 8, 1867, the “father of American literature” set sail on the pleasure cruiser Quaker City for a five month trip through Europe and the Middle East. His record of that trip turned into one of his earliest works, a lampoon of the people and customs of the region titled The Innocents Abroad or The New Pilgrim’s Progress—proof that he was an equal-opportunity satirist who could find humor in just about everything (and everyone).

The Saints had gathered to Zion partly so they could be in a location remote enough that they could be left in peace to practice their religion. But that remoteness also encouraged the area to become “a gathering place and focal point for a myriad of jokes, myths, and distortions which would long go uncorrected.” As former LDS Church Historian Leonard J. Arrington believed, the well-attended public lectures and writings of eminent 19th century humorists—among them, Mark Twain—probably did much to influence national attitudes and, consequently, national policies regarding the Mormons.

However, Mark Twain's writings about Mormons were based on a single trip to the Nevada Territory, where Mark Twain crossed paths with the Mormons when his entourage stopped in Salt Lake City for two days.

What was meant to be funny quickly became biting, but it seems Twain didn’t start out to be antagonistic towards the Church. “When I first began to lecture, and in my earlier writings,” he explained, “my sole idea was to make comic capital out of everything I saw and heard.” And that included the Mormons, whom he saw as a “popular, humorous topic capable of yielding a great deal of low-grade ore, which he had the ability to mine effectively.”

Twain’s sarcastic recounting of his two days in Salt Lake ended up as several chapters in the diary of his journey to Nevada and his life in the American West—a book originally titled The Innocents at Home, and eventually renamed Roughing It. Anyone today who reads his reflections on the Mormons must keep in mind that his exposure to them was limited to only two days. And that he didn’t write his account for more than a decade after his stopover in Salt Lake City. In fact, when he started to put pen to paper in an attempt to write the “Mormon chapters,” he wrote to his brother, Orion, “Do you remember any of the scenes, names, incidences or adventures of the coach trip?—for I remember next to nothing about the matter.” He then asked Orion to jot down some things he remembered about the trip.

Between them, they were able to remember enough to weave a few chapters dripping with sarcasm about everything from “Mormon booze” and the stature of Brigham Young to polygamy and the Book of Mormon. Of course, the missionary-minded Saints in Salt Lake had made sure Twain didn’t conclude his visit without his own copy of the ancient record, and somebody obviously took some time to explain what it was—because Twain’s reflections about the Book of Mormon were peppered with lots of authentic detail.

His musings suggest that he must have read parts of it—or, at the very least, tried to read it. “All men have heard of the Mormon Bible, but few [have] taken the trouble to read it,” he wrote. Admitting that he left Salt Lake with one of the books, he summarized, “The book is a curiosity to me. It is such a pretentious affair and yet so slow, so sleepy…”

In reporting on some Book of Mormon accounts, he goes into startling detail. The Book of Ether seemed to particularly capture his imagination. Again, his witty interpretation of events is woven through his accurate report of events, causing us to wonder exactly where Twain stands. Here, for example, is his report of the negotiations between Coriantumr and Shiz, which almost qualifies as an "Ether for Dummies" account:

Coriantumr, upon making a calculation of his losses, found that “there had been slain two millions of mighty men and also all of their wives and all of their children.” Say, five or six million in all. “And he began to sorrow in his heart. . . .” Unquestionably it was time. So he wrote to Shiz asking for a cessation of hostilities and offering to give up his kingdom to save his people. Shiz declined except on the condition that Coriantumr would come and let him cut his head off first. A thing which Coriantumr would not let him do.

But by far, Mark Twain’s favorite subject about the Mormons was polygamy. Twain seized the opportunity to “excite wide reading and listening audiences by speaking with poker-faced solemnity about the perils of going, unattached, among the marrying Mormons.” According to Twain, he offered a sage piece of advice to one man, urging him not “to encumber yourself with a large family . . . Take my word for it, ten or eleven wives is all you need—never go over it.”

Twain’s conclusion about Utah, summed up in Roughing It, pretty much says it all:

All our information had three sides to it and so I gave up the idea that I could settle the Mormon question in two days. Still, I have seen newspaper correspondents do it in one. I left Great Salt Lake a good deal confused as to what state of things existed there and sometimes even questioning in my own mind whether a state of things existed there at all or not.