Skeptics have sometimes compared the Book of Mormon to the work of J.R.R. Tolkien, including his epic trilogy The Lord of the Rings. If, they reason, Tolkien could create an entire imaginary world, with a large and detailed geography and a complex history that involves multiple ethnic groups, wars, and intricate subplots, it’s surely not impossible to imagine that Joseph Smith might have done the same.

Of course, there are some differences between them. For example, Joseph Smith was a marginally literate frontier farmer who dictated the Book of Mormon in less than three months and always insisted that it represented genuinely ancient history. By contrast, Tolkien, who created his Middle Earth over the course of many decades and never claimed it was other than fiction, was an accomplished philologist and translator. He taught at Oxford University as the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon and then as the Merton Professor of English Language and Literature.

However, a new comparison of the Book of Mormon to the works of Tolkien is well worth considering. In their intriguing article “Comparing Book of Mormon Names with Those Found in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Works: An Exploratory Study,” four Brigham Young University professors — Brad Wilcox (ancient scripture), Wendy Baker-Smemoe (linguistics), Bruce L. Brown (psychology, with specialization in the psychology of language), and Sharon Black (education, with a focus on writing and editing) — look specifically at the unusual names found within both Tolkien’s books and the Book of Mormon. (It's published on mormoninterpreter.com, of which I am the chairman and president.)

They focus on “phonemes,” the smallest units of sound, using a hypothetical construct that they term a “sound print” or “phonoprint.” This is a pattern of sound that — rather like the individual “wordprint” seems to characterize different writers or like the fingerprints that are used to identify and specify the perpetrators of criminal acts — appears to be distinctively characteristic of individual authors and could, therefore, serve to differentiate one writer from another.

“Traditionally,” say the authors of this new study, “words have been seen as the smallest building blocks over which authors have some freedom to choose. This new line of research expands the fundamental unit of text into phonemes and proposes the possibility that we could produce a phonoprint that would differ from author to author. Despite that authors have fewer sounds with which to create words than they have words with which to create prose and poetry, there is some evidence that authors favor certain sounds over others when choosing or inventing names.”

Using this fresh and unusual research approach in an “exploratory” fashion, the authors examine the dwarf, elvish, hobbit, and human names created by Tolkien, as well as the Jaredite, Nephite, Mulekite, and Lamanite names found in the Book of Mormon. Although Joseph Smith always maintained that he had translated the Book of Mormon from an ancient record, his critics have frequently claimed that he wrote it himself, just as any ordinary writer composes a fictional narrative. Presumably, if those critics are right, he would have chosen the names for his imaginary world, or created them, just as other writers of fiction do.

Their summary of their findings is worth quoting:

“Results suggest that Tolkien had a phonoprint he was unable to entirely escape when creating character names, even when he claimed he based them on distinct languages. In contrast, in Book of Mormon names, a single author’s phonoprint did not emerge. Names varied by group in the way one would expect authentic names from different cultures to vary. . . . Thus the Book of Mormon name groups were significantly more diverse than Tolkien’s. . . . If the Book of Mormon names were created by an individual, they were created by a very different process or based on languages more different from each other and consistent within themselves than those created by Tolkien.”

For Tolkien, the invention of fictional languages was a lifelong hobby that contributed substantially to his creation of Middle Earth. He began developing “Elvish” in his late teens, for example, and was still working on its history and grammar at age 81 when he died in 1973.

It seems highly unlikely that Joseph Smith was better at inventing fictional languages than Tolkien was.

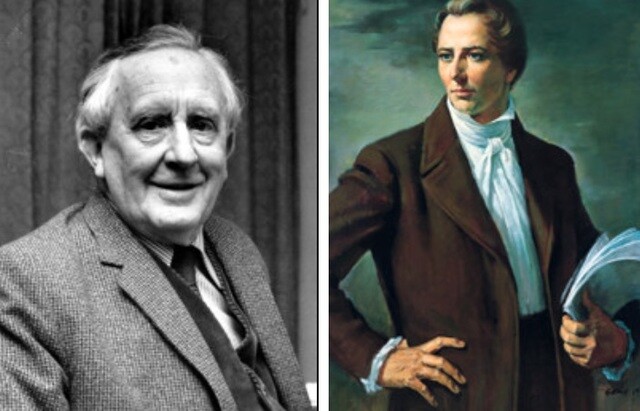

Lead images of J.R.R. Tolkien (Associated Press) and Joseph Smith (Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Daniel Peterson teaches Arabic studies, founded BYU’s Middle Eastern Texts Initiative, directs MormonScholarsTestify.org, chairs mormoninterpreter.com, blogs daily at patheos.com/blogs/danpeterson, and speaks only for himself.