As the father of six, grandfather of twenty-nine, and great-grandfather of more than sixty, Dallin H. Oaks loves the family. This has been one of the most frequent themes of his apostolic ministry. In his first year as an Apostle, he spoke at a fireside for parents on “parental leadership in the home.” “We cannot overstate the importance of parenthood and the family,” he said. “The basis of the government of God is the eternal family.” He affirmed “that the gospel plan originated in the council of an eternal family, it is implemented through our earthly families, and it has its destiny in our eternal families.”1 These principles were reflected in his family teachings, priorities, and practices.

After his father’s death, young Dallin Oaks spent two years on his grandparents’ farm. “In my boyhood on a farm,” he explained, “every evening was a family home evening, and there was no television to distract us from family activities. Aside from brief hours at school, whatever happened during the day happened under the direction of the family.” Now, he recognized, with urban living, “very few of our youth experience the consistent family-centered activities of earlier times.”2 Consequently, he and June sought every opportunity for their children to work together under their leadership.

Elder Oaks working in his yard

June taught the daughters, and Dallin tried to find meaningful home and yard work and part-time employment for the sons. He practiced what he preached. After the children married, Dallin took over cutting the lawn, which amazed and amused the neighbors. They marveled to see him dressed in old overalls and a baseball cap.

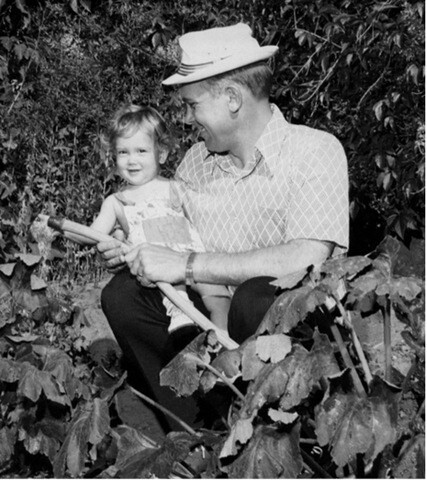

Gardening lent itself easily to teaching gospel principles. “Dad wanted us to know about the principle of sowing and reaping,” Lloyd said, “that when we did specific things, . . . there were specific rewards or consequences attached. If we wanted the fruits of labor, we had to labor. . . . He saw the principle of planting and sowing as a general life lesson, and one consistent with eternal principles.” Stories of working with Grandpa became legendary.

Elder Oaks’s policy had long been to “work first and play later.” Even while on a family vacation at a friend’s ranch, he had grandsons help cut Canadian thistles to leave the place better than they found it. Working together was not just toil—it was a time to bond, to achieve goals, to accomplish good, and to experience service. As much as some family members complained at the time, they retained memories of family work projects and remained proud of what they did together.

With Jenny in the garden, about 1978

Daughter TruAnn said her father’s motto sometimes seemed like “work first and play never,” but it had a positive influence on family members. “He has the most impressive work ethic and gets more done than anyone else I know,” she said. “Both he and Mom kept themselves busy working on projects, and many of us follow their examples and take projects with us wherever we go.”

Other family activities included trips together (camping when the children were younger and family income was limited), walks in wooded areas, and reading together. They traveled over much of the United States, often stopping at historical markers. “I love that Dad had us stop and read all the historical markers that we encountered, even though sighs could be heard from the back seat,” TruAnn said. “He passed to me a real love of learning. He was always eager to learn something new.”

Family scripture reading was supplemented by reading from the classic Hurlbut’s Stories of the Bible, which Dallin had read as a boy on the farm. Dallin and June frequently told stories from their early experiences and their ancestors’ histories. Other favorites during family gatherings were selections from the published poems of James Whitcomb Riley, especially his “Bear Story,” which Dallin’s mother had read to him when he was a child.

“President Oaks’s children adore and respect him and desire to be with him whenever possible,” Kristen observed. “They love their daddy. He focuses on their welfare and is very proud of their accomplishments. They often call for advice or to report. They respect his wisdom and impressions. They appreciate his work ethic, his love and loyalty to their mother, and his devotion to the Lord. They saw him put the Lord first in his life. Having tasted the joys of the gospel, material things are not important to him. He was still using a fishing pole and waders from the 1980s until fishing friends bought him new ones. Pioneer-like, his motto is ‘Use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without.’”

► You may also like: Matchmaking by a fellow Apostle, an unexpected job resignation, and a baseball cap: The story behind President and Sister Oaks’s first date

“Dad was thrifty and frugal because of lessons from his mother and his grandfather Harris while on the farm in Payson,” son Lloyd explained. “Dad told me that his grandfather Harris . . . one day tasked him to remove nails from some boards, stack the boards, and straighten the nails for reuse. Dad complained to his grandpa, stating that he should just spend fifteen cents on new nails. Grandpa Harris replied, ‘I have never had fifteen cents to spend on nails.’”

Son Dallin D. also remembered that their father created projects for them to instill the work ethic he learned as a youth. “Dad would work alongside of us. He wasn’t just saying go out and do all this work. He’d work alongside of us.” He wanted his boys to experience the benefits of working with their hands. “We wanted to be with Dad,” Dallin said, “and we wanted to have that time with him. . . . I liked being with him, but I didn’t necessarily like doing some of that kind of work.”

Elder Oaks taught that parents should avoid overscheduling their children with things that were good but not essential. Instead, they should preserve time for a kneeling family prayer every morning and personal prayers every evening, family scripture study, family home evening, and the one-on-one time that binds a family together and fixes children’s values on things of eternal worth. He sought to live by those principles in his own home.

In the Oaks family, a meal with Father or Grandfather Oaks became a time of laughter when he could relax and laugh heartily, engage in friendly banter, and offer words of wisdom. “In small groups,” son Lloyd said, “he is engaging and funny and has an amazing sense of humor. You don’t get to see that from the pulpit when he is talking about weighty things.” Son Dallin agreed: “My dad’s pretty funny, if you get to know him. He doesn’t show that side so much from the pulpit in general conference. But he has a great sense of humor. He loves telling funny stories.”

Once when a grandson had a disastrous period in grade school, his distressed parents showed Elder Oaks the boy’s report card showing four F grades and one C. Eager for solutions from the wise grandfather, the parents listened intently as he immediately reached a conclusion. Referring to the C, Elder Oaks jested, “He must have concentrated too much on one subject.”

One thing that made dinnertime conversation—or any conversation—meaningful for Elder Oaks’s family members was that he accorded their opinions great respect. All were expected to speak up, and no one was belittled. By example, Elder Oaks taught that God loves all His children. As a man who grew up with a strong mother and married young to a strong wife, “he was used to very strong women,” TruAnn said, “and women being in charge, and women being able to preside and fulfill responsibilities without the aid of a man.”

“What your children really want for dinner,” Elder Oaks taught in a talk, “is you.”3 As he said in another address, “There is abundant secular evidence that there is no substitute for the traditional family as a means to increase the likelihood of health, happiness, longevity, and prosperity in the parents and the total well-being of children. The family, as someone once said, is the only department of health, education, and welfare that really works.”4

Over dinner, Dallin and June Oaks naturally blended secular and spiritual topics, teaching by example the importance of being educated about both. “Our dinner conversations were about ideas,” daughter Sharmon recalled. “They were about the gospel. The conversations between my mother and father modeled knowing what’s going on in the world around you and dealing with it and how the Lord would deal with it.”

► You may also like: Nearly 37 years ago, President Oaks was called as an Apostle. Here's the behind-the-scenes story of that life-changing moment

As busy as he was outside dinner, Elder Oaks gave family members his time when they needed it. During their youth or childhood, if they had minor problems, they would take them to their mother. Major problems were different; those often went to Dad. “You could go in anytime with something that was important,” Sharmon remembered, “and he would put down his work and talk.”

When serving in the stake presidency in Chicago, he often had to travel long distances to visit local Church units. “When he is not here, . . . you can be proud of that,” their mother taught them, explaining that “he will be a better father because of that priesthood service.” Besides, just as Elder Oaks’s father seemed present in his life after he died, Elder Oaks’s children felt his presence even when he was gone.

When family members were away from him, they sometimes wished he were near. “I remember many times on my mission thinking, ‘I wish my dad were here, because he’d know what to do,’” son Dallin D. said. “He always seemed to know what to do. He always seemed to be able to make good decisions and act with great wisdom.”

This engaging biography by noted historian Richard E. Turley, Jr. takes the reader on a fascinating journey through the life of an extraordinary leader. It is filled with stories and photographs detailing his boyhood, his family life, his education and military experiences, and his distinguished academic and law career. Available now in Deseret Book stores and at DeseretBook.com.

- Dallin H. Oaks, “Parental Leadership in the Family,” Ensign, June 1985, 7.

- Oaks, “Parental Leadership in the Family,” 9.

- Dallin H. Oaks, “Good, Better, Best,” Ensign, Nov. 2007, 104–8.

- Dallin H. Oaks, “Values,” BYU Management Society, Dec. 17, 1998.