When the coast-to-coast telegraph was completed in Salt Lake City in October 1861, Brigham Young sent a clear signal to President Abraham Lincoln: “Utah has not seceded but is firm for the Constitution and laws of our once happy country.” Less than eight years later, on May 10, 1869, hundreds gathered at Promontory, Utah, to witness another coast-to-coast completion. The driving of the last spike of the transcontinental railroad reverberated continuity to a once broken nation.1

Railroad enthusiast Asa Whitney had strongly asserted that the Union Pacific Railroad would bring the nation “all together as one family, but with one interest—the common good of all.”2 Promontory was selected as the place of convergence, ending an intense rivalry between the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific railroads.

An Era of New Prosperity

The moment the final spike was struck, telegraph wires transmitted the simple but momentous communication, “D-O-N-E.” Instantly, news of the completion of the railroad spread across a nation that erupted in celebration. Cannons boomed in cities from the Atlantic to the Pacific. In Salt Lake City, 7,000 gathered in the tabernacle for the celebration. Promontory enjoyed bands from Fort Douglas and the Salt Lake City 10th Ward.3

As the nationwide celebrations faded, America entered an era of new prosperity with the expansion of commercial ventures. The uniting of the rails from the Pacific to the Atlantic suddenly brought the world much closer. Soon, the first transcontinental freight train left California bound for the East Coast, transporting Asian teas as well as passengers. Travelers could now cross the continent in a week instead of six months. Previously exorbitant overland travel costs were reduced to a mere $70 for emigrant rail passage.4

The impact of Utah’s contribution in building the transcontinental railroad and the state’s subsequent territorial benefits is a subject that merits attention. In 1869, Latter-day Saints made up 98 percent of Utah’s total population.5 In the same year, Samuel Bowles, editor and publisher of the Springfield, Massachusetts, Republican observed, “But for the pioneership of the Mormons, discovering the pathway, and feeding those who came out upon it, all this central region of our great West would now be many years behind its present development, and the railroad instead of being finished would hardly be begun.”6

A Peculiar People

Not only was the work the Latter-day Saints did for the railroad superior but Latter-day Saint construction camps were conducted in stark contrast to other “hell on wheels” encampments. Instead of boisterousness induced by whiskey, gambling, and prostitution, the Latter-day Saint campsites operated under orderly and peaceful religious governance. “Twice daily, workers and their families assembled for prayers and on Sundays they attended religious services. . . . Neither swearing nor drunkenness characterized their construction camps.”7 Clarence Reeder summarized the Latter-day Saint efforts to construct the railroad: “A people working together in harmony under the guidance of their religious leaders to accomplish a temporal task which they treated as though it were divinely inspired.”8

Music in the Latter-day Saint camps along the Union Pacific was sometimes provided by the Rocky Mountain Glee Club, comprised of the laborers. Homespun songs were sung by Latter-day Saints around the campfires, including this one written by Church member and grader James Crane:

At the head of great Echo

The railway’s begun

The Mormons are cutting

And grading like fun.

They say they’ll stick to it

Till it is complete,

When friends and relations

They’re longing to meet.9

Another favorite song was:

Hurrah, hurrah, the railroad’s begun.

Three cheers for the contractor, his name Brigham Young.

Hurrah, hurrah, we are faithful and true

And if we stick to it, it’s bound to go through.10

From Isolated to Insulated

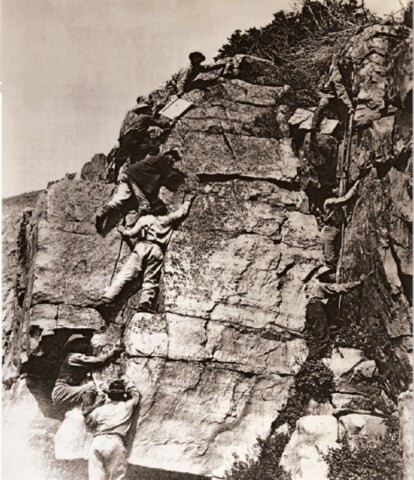

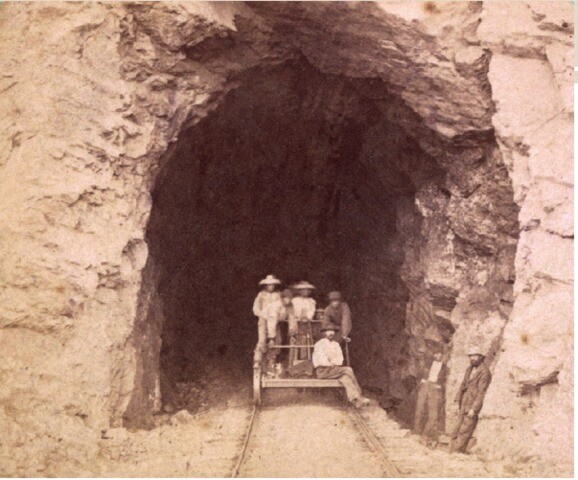

An estimated 5,000 Utahans did “stick to it,” laboring for both the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific, whose supervisors were complimentary of the grading, trestlework, bridge building, tunneling, and furnishing of ties completed in Utah.11

John J. Stewart wrote:

No state nor people figures more prominently in the story of the Pacific Railroad than do Utah and Utahans, particularly the Mormons. Mormon pioneers blazed the trail for much of the route of the railroad. The Mormon empire in the Great Basin provided much of the incentive for construction of the railroad. Mormons were among the first to petition Congress to construct the railroad. Brigham Young was one of the very first to subscribe to Union Pacific stock. Mormons provided much of the labor and capital in construction of the railroad, doing some of the surveying on Union Pacific and the grading on both Central Pacific and Union Pacific through Utah. . . . And Utah was to a peculiar degree both benefactor and beneficiary of the railroad, both as to passenger service and freight, for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints utilized the railroad greatly with its missionary and immigration programs, and the mining industry could be developed extensively only with the aid of railroad facilities.12

Some argued that Latter-day Saints did not want a railroad coming into Utah, as it would disturb their cultural isolation. According to Bowles, however, Brigham Young was quick to respond to that argument: “It must indeed be a damned poor religion if it cannot stand one railroad.”13

John Taylor likewise stated:

It has been thought and charged by some that we are averse to improvements, and that we disliked the approach of the railroad. Never was a greater mistake. We have been cradled in the cities of the new and old worlds, where we have built locomotives, steamboats, gas works, and telegraph lines. . . . We have always been the advocates of improvement of the arts, science, literature, and general progress; and whilst we abjure evils, the follies, the crimes, and many of the lamentable adjuncts of civilization, we are always first and foremost in everything that tends to ennoble and exalt mankind. . . . We meet in friendly conclave with distinguished gentlemen connected with the eastern and western divisions of the railroad. . . . We hail these gentlemen as brothers in art, science, progress and civilization. . . . We will bare our arms and nerve our muscles to aid in the completion of this great cord of brotherhood which is already reaching our borders.14

Utah’s consensus was that the benefits would outweigh the potential challenges. Utah’s citizens recognized they would no longer be isolated, so they created programs to insulate their people: a School of the Prophets, the re-emerged women’s Relief Society, and agricultural and manufacturing cooperatives. In addition, the Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution (ZCMI) was established to handle the purchase and distribution of wholesale items to shore up the city of the Saints.15

Blazing the Trail

During their journey to the West, Latter-day Saint pioneers laid the groundwork for a future railroad.

George A. Smith noted:

We started from Nauvoo in February, 1846, to make a road to the Rocky Mountains. A portion of our work was to hunt for the railroad. We located a road to Council Bluffs, bridging the streams, and I believe it has been pretty nearly followed by the railroad. In April 1847, President Young and one hundred and forty-three pioneers left Council Bluffs, and located and made the road to the site of this City [Salt Lake City]. A portion of our labor was to seek out the way for a railroad across the continent, and every place we found that seemed difficult for laying the rails we searched out a way for the road to go around or through it.16

Brigham Young also stated:

I do not suppose we traveled one day from the Missouri here, but what we looked for a track where the rails could be laid with success, for a railroad through this Territory to the Pacific Ocean. This was long before the gold was found, when this Territory belonged to Mexico. We never went through the canyons or worked our way over the dividing ridges without asking where the rails could be laid. When we came here over the hills and plains in 1847 we made our calculations for a railroad across the country. . . . We want the benefits of the railroad for our emigrants so that after they land in New York they may get on board the cars and never leave them again until they reach this city.17

The Blessings of the Railroad

The transcontinental railroad brought blessings to the Saints in a number of ways. For example, thousands of European converts were now able to gather to an American Zion in weeks rather than months, with passage across the Atlantic reduced to 11 days by improved steam-powered boats and travel across the US reduced to one week by rail. Employment on the railroad also provided Latter-day Saints in Utah with an immediate solution to a devastating problem. In 1868, Church members first contracted to work for the Union Pacific Railroad at a time when an insect infestation had brought the Saints to their knees. Crops were ruined, farmers were out of work, families needed to be fed, and there was a shortage of cash. Work on the railroad was a godsend.

Lewis Barney wrote:

The grasshoppers put in their appearance and destroyed our Crops it seemed that every avenue was Closed And the saints Cut off from supplies But the Lord who had brought them safe through all their troubles had not forsaken them For at this Critical time President Young was requested to take a heavy contract on the union pacific Railroad which he accepted this gave the Saints Labor for which they got Cash Clothing and provisions.18

In late May of 1868, Orson Pratt, writing to Brigham Young, also stated, “Much of our wheat in this settlement is eaten off by the grasshoppers; consequently, several are ready to go to work on the railroad.”19

Along with employment, there was also the hope of an expanded market to transport local goods to a national market. Further, steel tracks could carry large granite stones for the Latter-day Saint temple—a distance of 20 miles from Little Cottonwood Canyon to Salt Lake City. Instead of taking several days to carry a load of stone from the quarry by ox team, it took about an hour by rail. In addition, with increased visitors to Utah, Church members hoped that prejudices would soften toward the city of the Saints.20

This hope was realized when Mrs. Frank Leslie (wife of the famed New York publisher) took a trip by rail to Utah in the 1870s. Author Leonard J. Arrington records that Leslie perceived the impressive industry of the Saints that made the desert blossom as the rose and observed that Utah’s citizens were “‘better fed, better dressed, and better mannered’ than other Westerners, and lived in neater cottages, amid flowers and garden produce in profusion.”21

But the transcontinental railroad was more than a window to the Latter-day Saint mecca or a benefit to Utah’s inhabitants alone. It was built with the aim of producing more opportunities for all Americans to profit thereby and with the hope of generating greater national unity. Providentially, the words engraved upon the golden spike read: “May God continue the unity of our country as this railroad unites the two great oceans of the world.”

On the day of the railroad’s dedication, Reverend J. Todd of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, offered a prayer:

Our Father and God,. . . we have assembled here, this day, upon the height of the continent from varied sections of our country, to do homage to Thy wonderful name, in that Thou hast brought this mighty enterprise, combining the commerce of the east with the gold of the west to so glorious a completion. . . . We here consecrate this great highway for the good of Thy people. O God, we implore Thy blessing upon it, . . . that this mighty enterprise may be unto us as the Atlantic of Thy strength and the Pacific of Thy love.22

May we remember the immense price paid by those who completed this enormous undertaking—the calloused hands, aching arms, strained backs, and blistered feet of those who leveled the path and laid the rails under unrelenting circumstances. Regardless of size or strength, these diverse human beings linked rails that tied the nation together and prospered the whole. As we walk in the diversity of our daily lives, may we too leave tracks and form ties with the aim of benefiting the greater whole. Remembering our common humanity will keep our nation united and lay the rails for generations to come.

Lead image from wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Golden_Spike_ceremony,_Promontory,_Utah,_May_10,_1869.jpg

Notes

1. Stephen E. Ambrose, Nothing Like It in the World: The Men Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad 1863–1869 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000),368, notes coincidentally that Theodore Judah, the railroad visionary, and his wife, Ann Ferona, commenced their wedding union on this same day.

2. David Howard Bain, Empire Express: Building the Transcontinental Railroad (New York: Penguin Books, 1999), 14.

3. Ambrose, Nothing Like It in the World, 363, 366.

4. Ambrose, Nothing Like It in the World, 369.

5. http://www.city-data.com/states/Utah-History.html, Leonard J. Arrington, “The Transcontinental Railroad and the Mormon Economic Policy,” Pacific Historical Review, vol. 20, no. 2 (May 1951), 157, put the Latter-day Saint population for the year 1869 at about 75,000.

6. John J. Stewart, The Iron Trail to the Golden Spike (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1969), 176.

7. http://npshistory.com/series/archeology/rmr/16/clr2d.htm

8. Clarence Reeder, “A History of Utah’s Railroads,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Utah (1959), cited in Ambrose, Nothing Like It in the World, 287.

9. Wesley S. A. Griswold, A Work of Giants: Building the First Transcontinental Railroad (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1962), 270.

10. Cited in Ambrose, Nothing Like It in the World, 286.

11. Leonard J. Arrington, “The Transcontinental Railroad and the Development of the West,” Utah Historical Quarterly, vol. 37, no. 1 (Winter 1969), 10.

12. Stewart, The Iron Trail to the Golden Spike (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1969), 175.

13. Samuel Bowles, Our New West (Hartford, CT, 1869), 260.

14. Stewart, The Iron Trail to the Golden Spike (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1969), 184.

15. Orson F. Whitney, History of Utah, vol. 2, 238-39.

16. Whitney, History of Utah, vol. 2, 239.

17. Whitney, History of Utah, vol. 2, 240-41.

18. Autobiography and Diary of Lewis Barney.

19. Letter of Orson Hyde to Brigham Young, May 27, 1868, CR 1234/1, Reel 53, box 40, fd 6, Church History Library.

20. http://emp.byui.edu/PyperL/New%20EM%20Lessons/EM_8.htm

21. Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, paperback ed. 1966), 239.

22. “The Proceedings at Promontory Summit,” Deseret News, May 10, 1869.