To most of us, leprosy is a disease that only existed in Biblical times and meant misery and exile. But to Latter-day Saints in a small Hawaiian leprosy settlement known as Kalaupapa, the disease meant a community of unity, coupled with a faith in God that neither they nor their neighbors would trade for anything.

One Catholic priest, while reflecting on his life’s experiences, remarked that the two holiest places on earth were Jerusalem and Kalaupapa. This bold statement resonates with the thousands of people from a variety of faiths who have been deeply touched by Kalaupapa—a peaceful settlement lying quietly on a four-mile peninsula beneath the sheer, breathtaking cliffs on the Hawaiian island of Molokai. This smooth, beautiful peninsula seems appropriate to symbolize the universal love of a Supreme Being that embraces all four corners of the earth. Structures that have stood in this region for over a century include places of worship for Protestants, Catholics, Buddhists, and Latter-day Saints. All these religions worked together to make Kalaupapa a place of unconditional love—something desperately needed in our world today.

It was over a decade ago when I first encountered this sacred space where a community of exiled sufferers of leprosy once found solace. Reflecting back on it, it seems I experienced something similar to what Elder Matthew Cowley felt. (Elder Cowley was an apostle who then presided over the Pacific region.)

After Elder Cowley’s visit to Kalaupapa in the mid-20th century, he said, “I went there apprehending that I would be depressed. I left knowing that I had been exalted. I had expected that my heart, which is not too strong, would be torn with sympathy, but I went away feeling that it had been healed.” Elder Cowley added, “I [left] . . . appreciating my friends, loving my enemies, worshiping God, and with a heart purged of all pettiness. This is a transformation for me, and for it, I am indebted to the . . . Saints of Kalaupapa.”

CREATING THE LEPROSY SETTLEMENT

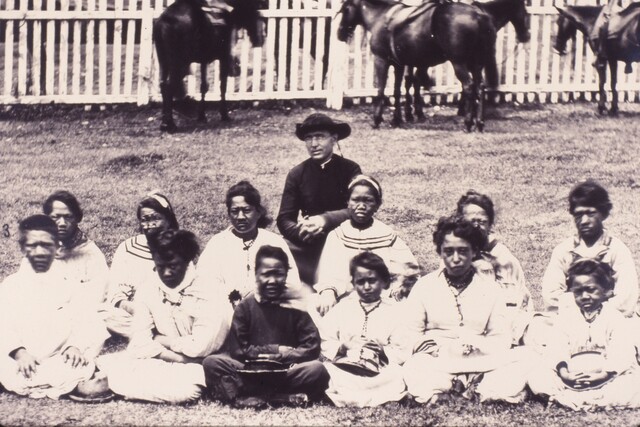

Photo courtesy of the LDS Church History Library

In January of 1865, the Hawaiian monarchy’s deep concern over the threat of leprosy, now known in the medical field as “Hansen’s disease,” caused King Kamehameha V to sign a document intended to prevent the spread of this malicious malady. Therefore, the Makanalua Peninsula (later commonly known as Kalaupapa), situated on the northern shores of Molokai, became a unique fortress with natural borders for victims who were viewed as inmates. As the new year dawned, a dozen patients were exiled there, the first of over 8,000 who would be separated from loved ones from 1866 to 1969.

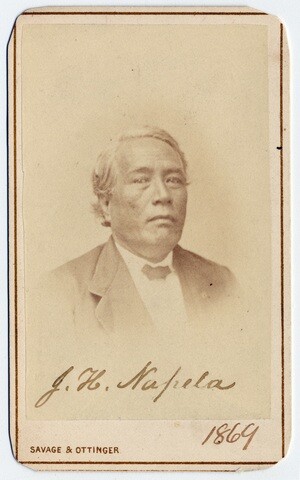

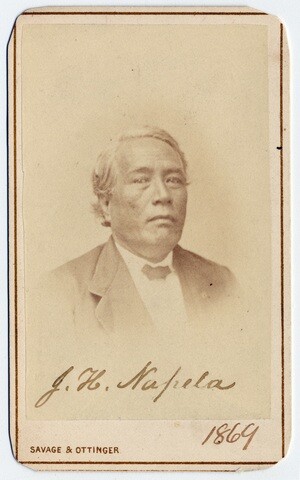

In 1873, two ecclesiastical leaders from different faiths came to the Kalaupapa peninsula. The first was a Latter-day Saint named Jonathan Hawaii Napela. The other was a Belgian Catholic priest, Joseph De Veuster, known better as Father Damien.

Napela had become a district judge in 1848 on Maui and converted to the Church four years later at age 39. He was a tremendous aid to early LDS missionary work on the Hawaiian Islands, where he assisted Elder George Q. Cannon with the translation of the Book of Mormon into Hawaiian. But one of his greatest legacies was his example as a devoted husband.

When his wife, Kitty, contracted the disease, Napela wanted to remain with her. Consequently, he wrote a letter in his native Hawaiian language, pleading with the Board of Health to allow him to remain with her at the settlement. He wrote, “I vowed before God to care for my wife in health and sickness. . . . I want to be with my wife . . . but with this disease, it will quickly shorten her life. Such is the reason for this petition.” His heartfelt petition was granted. He remained with her for the duration of his life in Kalaupapa (1873–1879), where he was also the acting branch president. Sadly, Napela also contracted the disease and died about two weeks before his wife did.

But Napela was not the only religious figure watching after those in the settlement. Father Damien arrived at the Kalaupapa peninsula about the same time Napela did, though he outlived his LDS counterpart by a decade. This loving, fearless man had an attitude of selfless service best captured by his own words: “Suppose the disease does get my body. God will give me another one on Resurrection Day.” From the day of his arrival in 1873 until his death at age 49 in 1889, his concern was for all, regardless of race or religion.

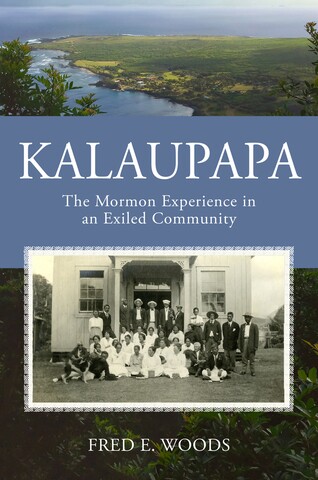

Learn more with Fred E. Woods' new book, Kalaupapa: The Mormon Experience in an Exiled Community.

In the 19th century, Hansen's disease, more commonly known as leprosy, spread through the Hawaiian Islands, causing the king of Hawaii to sanction an act that exiled all people afflicted with this disease to Kalaupapa, a peninsula on the island of Moloka'i. Kalaupapa was separated from the rest of the world, with sheer cliffs on one side, the ocean on the other three, and limited contact with anyone, even loved ones. In Kalaupapa, the author delves into the untold history of Kalaupapa and its inhabitants, recounting the patients' experience on the peninsula and emphasizing the Mormon connection to it. By so doing, he brings to light inspiring stories of love, courage, sacrifice, and community.

Soon after their arrival at the settlement, Napela and Father Damien became acquainted. The two men became dear friends, despite the fact that Father Damien was 27 years younger than Napela, from a very different cultural background, and a committed leader of a different faith. In fact, one of their contemporaries who lived at Kalaupapa wrote, “After Father Damien arrived in the Leper Settlement . . . Mr. J. Napela . . . and Father Damien were the best of friends.”

What makes this particularly unusual is that at this time in Hawaii, heated rivalries existed between faiths as they vied for island converts. But at Kalaupapa, there seems to have developed a different kind of spiritual terrain, nourished by the relationship between these two great men and their commitment to improve the deprived conditions they encountered upon their arrival at the settlement. Both had come to Kalaupapa to serve, and in the end, both contracted leprosy as a result of their intimate service and charity.

FINDING HEAVEN IN AN EARTHLY HELL

It appears that through the influence of Napela, Father Damien, and a number of other devoted Christians, the community began to be transformed. Over the years, Kalaupapa softened under the strain of shared suffering. Bernard, a former patient, noted that Kalaupapa used to be viewed as “a devil’s island, a gateway to hell, worse than a prison.” Yet he added, “It is a gateway to heaven. There is a spirituality to the place. All the suffering of those whose blood has touched the land—the effect is so powerful even the rain cannot wash it away.” LDS patient Makia Malo noted, “They called it hell, and we called it heaven.”

Some patients related how their testimonies of prayer were strengthened as a result of their experience at Kalaupapa. For example, Protestant member Nancy Talino related, “We were nurtured. . . . Not just by a Protestant or a Mormon or even Catholic nuns. Everyone worked together. . . . Everyone needed prayers; there were prayers. And I was thankful that I was very close, very close to God.” A Catholic patient who came to Kalaupapa at age 14 in 1936 also shared her experience of prayer and the importance of expressing gratitude to God, even in times of adversity: “God knows best for us. . . . You must keep your faith no matter what comes into your life. . . . I feel religion is not thanking God when everything is good; religion is thanking God when everything isn’t going right.”

This relationship with the heavens seems to have also affected the relationships among the patients themselves. Several people who have had contact with the Kalaupapa patients have been amazed by the unifying effects of suffering from the same disease. For example, in his book Travels to Hawaii, Robert Louis Stevenson wrote of his visit to Kalaupapa, explaining, “They were strangers to each other, collected by common calamity.” Protestant writer Ethel H. Damon noted, “Surely the isolation of suffering has tended toward obliterating the barriers in religious observance.” Reverend James Drew observed, “They are brothers and sisters here. . . .Leprosy has made sure of that.”

Asian patient Paul Harada echoed this same theme: “The more suffering, the closer we are together. . . . We are all friends here.”

FINDING UNITY AT KALAUPAPA

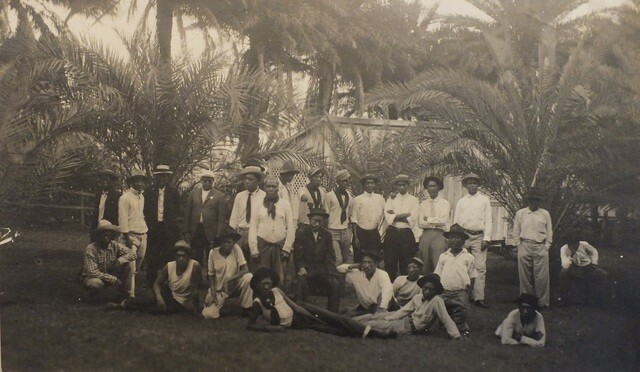

In a number of interviews conducted over the past years, signs of the unifying culture of Kalaupapa abound.

Latter-day Saint Kuulei Bell related that several times she was recruited to sing in the Catholic choir.

Richard Marks—a former patient, a Catholic, and sheriff of Kalaupapa for nearly two decades—boasted of his unusual record of having made no arrests in his time as sheriff. In describing the Catholic mass in Kalaupapa at Christmastime, Marks recalled, “The Protestants and the Mormons came early, and they took the back seats so we had to sit up front.” Another Catholic patient noted, “When we had a function going on, the whole community just comes together.”

Apparently this kind of inclusive attitude ran throughout the 20th century at Kalaupapa. Latter-day Saint convert Mary Sing recalled, “When I came [to Kalaupapa in 1917], everybody was living just like a family. Nobody says anything bad about the other religions. Everybody was together. They respected each church.” Sing added, “If the Catholics had a party . . . they [would] wait for the Mormon people to get through with their service. . . . And so [it] is with the Protestant; everybody was happy.” One Protestant patient, Edwin Lelepali, known affectionately as “Pali,” recalled, “Us and the Catholic Church and the Mormon Church, we’re always getting together.”

A particularly memorable multi-faith service occurred soon after a cross was erected at the Kauhako Crater, shortly before Easter of 1948. One author wrote of the assemblage of different Christian faiths: “The two Mormon elders [assigned to the area] assisted Pastor Alice in the service; many Roman Catholics were present. . . . The people sang as never before, their joyous message carrying on the wind even to the sufferers in the hospital at Kalaupapa.”

Perhaps the most impressive piece of Kalaupapa’s interfaith collaborative work was in the construction of various places of worship. Members of all faiths throughout the settlement joined in 1966 to help restore the Protestant Siloama Chapel at the time of the centennial anniversary of the incorporation of the Protestant church at the settlement. Said Lelepali of the occasion, “We had the Protestants, we had the Catholics, we had the Mormons all chip in to build this church. . . . They wanted to help this church. . . . When you came here, you could feel the spirit of love. It was special working with them. . . . It was just beautiful.”

When asked on another occasion if this same support occurred when a 20th century Catholic church was erected in the settlement, he observed that everyone joined in “to help raise some funds for the church. . . . Everybody would help out, and that’s how it was in Kalaupapa. That’s what’s so different about Kalaupapa. . . . When somebody needs help, everybody’s there.” Finally, this patient explained, “This is our family. . . . I don’t care what religion. . . . That’s how we felt. When they need help, we [are] there.”

This same spirit of love and collaboration in building the Catholic and Protestant churches was also strongly evident in 1965 when a new LDS chapel was constructed to replace an older chapel, which had deteriorated. When the building was dedicated at the close of the year and the work hours were tallied, it was discovered that those of other faiths had actually donated more hours in its construction than Latter-day Saints had. “All worked hard, and some of those with disabilities had their hands wired to the wheelbarrows that they might do their share.” The entire settlement joined in a celebration of joy knowing that their LDS friends had a new chapel to worship in.

BECOMING CHARITY ITSELF

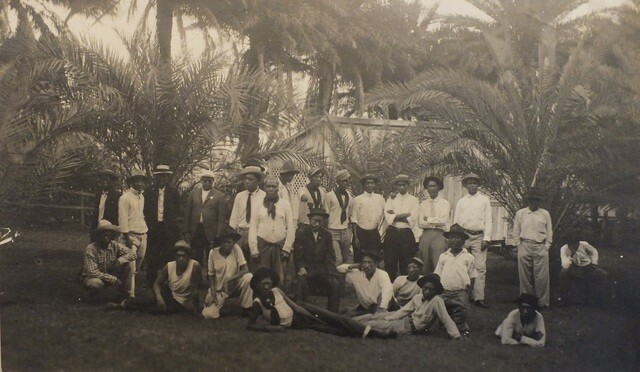

Photo courtesy of Damien Collection Leuven

The charity and uncommon service rendered at Kalaupapa is a reminder of the importance of building bridges instead of barriers, finding common ground instead of battleground, and valuing one another regardless of differences.

Elder Orson F. Whitney noted in a general conference address that God “is using not only his covenant people, but other peoples as well, to consummate a work, stupendous, magnificent, and altogether too arduous for this little handful of Saints to accomplish by and of themselves. . . . Other good and great men have been sent by the Almighty into many nations to give them . . . that portion of truth that they were able to receive and wisely use.”

The story of Kalaupapa also reminds us to look outside our religious circles into the faces of those of other faiths and to seek after the greatest spiritual gift: charity. This unique settlement of years past urges us today to apply the ever-pertinent Latin maxim: “In the essentials, unity; in non-essentials, liberty; and in all things, charity.”

Kalaupapa translated means “flat plain” or “flat leaf,” and coming to Kalaupapa was surely a leveling experience for all—a way to cross the boundaries of professed belief and ethnicity into a larger realm of endless brotherhood and compassion. For it was here that religious denominations and cultural divides dissolved; it was here that the love of God was manifested in a magnificent way.

Learn more with Fred E. Woods' new book, Kalaupapa: The Mormon Experience in an Exiled Community.

In the 19th century, Hansen's disease, more commonly known as leprosy, spread through the Hawaiian Islands, causing the king of Hawaii to sanction an act that exiled all people afflicted with this disease to Kalaupapa, a peninsula on the island of Moloka'i. Kalaupapa was separated from the rest of the world, with sheer cliffs on one side, the ocean on the other three, and limited contact with anyone, even loved ones. In Kalaupapa, the author delves into the untold history of Kalaupapa and its inhabitants, recounting the patients' experience on the peninsula and emphasizing the Mormon connection to it. By so doing, he brings to light inspiring stories of love, courage, sacrifice, and community.