Editor’s note: This article was originally published on LDSLiving.com in July 2022.

Latter-day Saints are known for our somewhat inventive cuisine: Funeral potatoes galore, every variation on Jell-O yet known to man, and copious soda combinations. But did you know there is another special food with Latter-day Saint roots? I’ll give you a few hints as to what delectable snack I’m talking about:

Small.

Thumb shaped.

Can be either baked or fried (delicious either way).

Often dipped in ketchup, but fry sauce is ideal.

Can often be found in Napoleon Dynamite’s pocket.

That’s right, folks: We have a Latter-day Saint to thank for the beloved Tater Tot. The inventor extraordinaire’s name is F. Nephi Grigg, and his story to potato fame is as inspiring as it is entertaining.

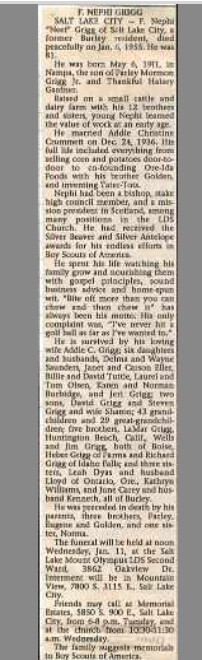

F. Nephi Grigg, or “Neef” as he liked to be called, was born in Nampa, Idaho, in 1913 and was the great-grandson of the apostle Parley P. Pratt. According to a Deseret News article, by age 12 little Neef was already an entrepreneur, selling produce from the family garden door to door around the neighborhood.

▶ You may also like: Shrimp, onions, and mayo in Jell-O? One Latter-day Saint turns it into art

He later dropped out of high school and joined his 12 brothers and sisters working on the family’s small cattle and dairy farm. In 1936, he married Addie Christine Crummett on a car lot on Christmas Eve. Why a car lot? The dealer had promised to give a car to the first person married on his lot on Christmas Eve, and Neef was never one to pass up a good deal. In relating the story to his grandchildren years later, he told them that when “opportunity passes by, you have to grab it by the forelock because it’s bald behind.”

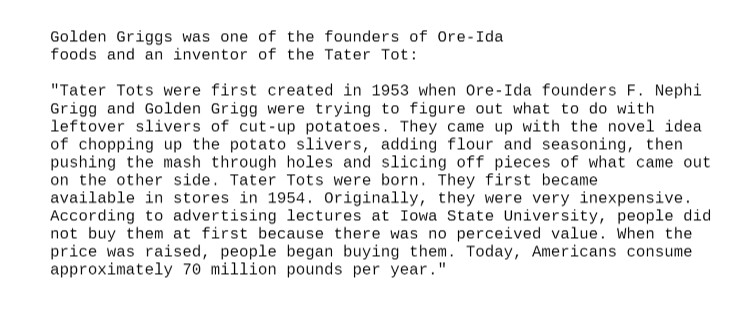

Another opportunity would later pass Neef’s way, and all of us Tot lovers are eternally indebted to him for taking it. After World War II, a frozen-food craze swept the US: Americans bought 800 million pounds of frozen food between 1945 and 1946—and Neef wanted in on the business. So he and his brother Golden and several other men, including Ross Erin Butler who would become the corporate secretary, mortgaged their farms so they could afford a down payment on a flash-freezing plant in Northeastern Oregon. They paid $500,000 for it (over $4.5 million today) and named their new company Ore-Ida because Neef and Butler had a passion for Boy Scouts and had been part of the Ore-Ida Scout Council. It was a bold move, but Neef was one who never seemed to lack in confidence. Records say his motto was always “Bite off more than you can chew, and then chew it”—a motto that makes a lot of sense when you consider he was surrounded by delicious Idaho potatoes his whole life.1

By 1951, Ore-Ida was the largest supplier of frozen sweet corn in the US, but Neef knew the real money was in French fries. As French fry production picked up, however, Neef was frustrated by all the scraps that were discarded after the potatoes had been cut down into fries. Those scraps were sold for a pittance and fed to cattle, but Neef was determined to find a way to feed them to people. So he decided to boil ’em, mash ’em, and stick ’em in a … totally new kind of frozen food.

The potato scraps were mashed together, seasoned, and baked, and a creative member of Ore-Ida’s marketing team came up with an all-too-cute and perfect name for the new product: Tater Tots.

Neef came up with quite the plan to launch Tater Tots into stardom. He and Golden traveled all the way to the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami. The brand-new hotel was on Millionaire’s Row right next to the sparkling white sands of Miami Beach. The Fontainebleau was posh, luxurious, and, most importantly, home to the 1954 National Potato Convention. According to Eater.com, Nephi brought 15 pounds of Tater Tots and somehow convinced the chef at the hotel to cook them up and serve them in small saucers as samples to the convention attendees. “These were all gobbled up faster than a dead cat could wag its tail,” Neef would later write.

▶ You may also like: 14 Things you didn’t know a Latter-day Saint invented

The little potato snack became available in grocery stores that same year, but according to one record, they were very inexpensive at first and did not sell well because of their low price point. Buyers didn’t understand the value or see a use for such a cheap, relatively unknown product. But once the price was raised, people began buying them—and they didn’t stop.2 Thanks to Tater Tots, Ore-Ida gained 25 percent of the frozen potato market in the 1950s. A second plant was opened in 1961, and Grigg sold the company to H.J. Heinz Company in 1965 for $30 million, which would be about $411 million today.

Tater Tots’ reign has carried on with style: Americans consume approximately 70 million pounds of Tater Tots a year, which breaks down to about 3.7 billion individual little tots. The snack has spread around the world, too. In Australia, for example, tots are widely called “potato gems,” and other brands have come up with their own names: “tater treats,” “tasti taters,” “potato crunchies,” and “spud puppies”—all of which Ore-Ida’s website calls imposters or “imi-taters.” (Ore-Ida owns the copyright to the name “Tater Tots” and is pretty proud of it, as they should be.)

And we can’t talk about Tater Tots without mentioning their cultural impact. What would the classic BYU-alumni produced film Napoleon Dynamite be without them? If you don’t know what I’m talking about, treat yourself to the iconic clip of Napoleon getting his trusty pocket tots crushed:

Napoleon’s love for tots was so memorable that years later Burger King hired the two original stars of the movie to film a commercial for their cheesy tots:

And in 2018, Y Magazine hired an artist to create an image of Napoleon entirely out of Tater Tots for the cover of their spring issue:

And while Tater Tots may have turned into a bit of a phenomena, they’re not the only hallmark of Neef Grigg’s life. In addition to running his business, Neef served as a bishop, a stake high councilor, and even a mission president in Scotland. He also received the prestigious Silver Beaver and Silver Antelope awards for his service to the Boy Scouts of America.

He and his wife had six daughters and two sons, and at the time of his death, Neef had 43 grandchildren and 29 great grandchildren. His obituary says that “he spent his life watching his family grow and nourishing them with gospel principles, sound business advice, and home-spun wit.” Ross Erin Butler, corporate secretary of Ore-Ida Foods wrote of him, “One of the greatest blessings of my life is the fine group of associates that I enjoy in church, business, and civic life. Foremost of these is F. Nephi Grigg, who I consider [a man] of God.”3

Natalie Grigg Brown is a returned missionary living in Provo and descendant of Neef who has heard tales of him since she was a little girl.

“Growing up, my parents would mention the story from time to time, and it always won me major bragging rights in the elementary school cafeteria!” she told LDS Living. “I wish I could say that we had Tater Tots front and center at every family reunion, but alas it was never really a huge deal.”

Alas indeed! If you, however, would like to pay your respects to the Tater Tot king, he is buried in the Mountain View Memorial Estates in Cottonwood Heights, Utah.

If this brief history of the Tater Tot hasn’t satisfied your appetite, Neef left us the gift of a five-and-a-half page personal account of how Tots came to be, which he called “History of the Tot.” You can find it safely housed at the J. Willard Marriot Library at the University of Utah.4

Now my only question is whether or not Neef had any spiritual impressions to help him create these bites of potato heaven. I suppose we’ll never know for sure, but as we learn in Sunday School, all good things come from above, right?

▶ You may also like: Quilting sensation Jenny Doan on faith, creativity, and accidentally building an empire

Notes

1. See Grigg’s obituary:

2. See source from Grigg’s profile on Family Search:

3. See document from Grigg’s profile on Family Search:

4. You can also read more about the Ore-Ida company in Isle of View, a biography about Ross Erin Butler written by MaryAnne Butler Ashton. Isle of View was published by BYU Press in Provo in 2013. A copy is available at the Church History Library.

Editor's note: Additional information was added February 2023.