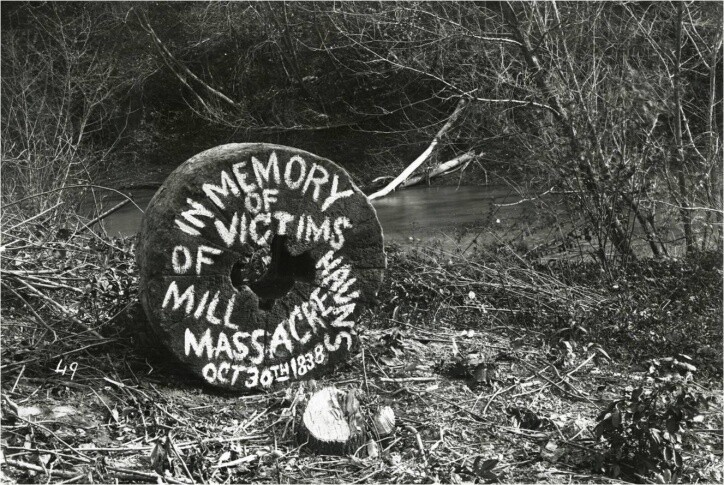

George Edward Anderson 1907 photograph of original Haun's Mill millstone. Church Archives, via Juvenile Instructor.

On October 30, 1838, more than 200 Missouri militiamen attacked the Hawn’s Mill settlement located on Shoal Creek in Caldwell County, Missouri, where dozens of Mormon families lived. On that day, the Missouri militia opened fire on the small community, shooting into the small crevices of the blacksmith’s shop where several Mormon men and boys had taken refuge.

The organized Missouri militia then entered the building to execute more. At the end of the horrific slaughter, 17 Mormons lay dead in pooled blood, more than a dozen others were wounded, some Latter-day Saint women were assaulted, and many Mormon men, women, and children had fled or hid in the woods. It was the violent crescendo of the 1838 Mormon War in Missouri.

In the days preceding the attack, Missouri militia visited Jacob Hawn’s Mill. (Hawn, whose name has historically been misspelled as Haun, was an early settler in Caldwell County and established a milling business there prior to the Mormons’ settling in that location. He was not a church member and never joined the LDS Church.) The militiamen threatened and disarmed the Mormon residents. These pre-massacre initiatives suggest that the militia planned to act before Missouri Governor Lilburn W. Boggs issued the Extermination Order on October 27, 1838.

Hawn appears to have been a major reason why Mormons at the mill did not follow Joseph Smith’s counsel to move away from the settlement and in closer to Far West for safety. Due to the growing threat of the militia, Smith informed Hawn that they should abandon the mill so as to not risk the lives of the Saints living there.

However, when Hawn returned to the settlement, he reported that Smith said the Mormons could stay and maintain the mill. Hawn may have been motivated by the fact that he stood to lose his livelihood if the Mormons were to abandon the settlement.

The Missouri militiamen disdained church members. Nathan Kinsman Knight, an observer to the massacre, stated, “At the Blacksmith shop they had killed Bro. Warren Smith and one of his sons and wounded the other. The boys were under the bellows pleading for their lives. The mob put their guns thru between the logs and fired.”

The Missouri militiamen who indiscriminately shot at church members demonstrated their vitriol towards and desire to exterminate all Mormons at Hawn’s Mill by shouting the phrase, “Kill them … Nits make lice.”

The Hawn’s Mill victims clearly felt that their suffering was because of their religious convictions. “In this boasted land of liberty,” wrote Amanda Smith, the Missouri militiamen demanded that she and her fellow religionists “deny [their] faith or die.” Amanda, whose husband and son were killed and who had another son seriously wounded in the blacksmith’s shop at Hawn’s Mill as described above, did not renounce her beliefs. She led what remained of her family through the cold, sleeping outdoors the whole way to Quincy, Illinois.

Without access to horses or wagons, many of the Saints walked in wintry conditions from Missouri to Quincy. John Hammer, who was just 9-years-old at the time, vividly remembered the stark conditions of the forced exodus from Missouri. In a stirring account he recalled:

When night approached we would hunt for a log or fallen tree and if lucky enough to find one, we would build fires by the sides of it. Those who had blankets or bedding camped down near enough to enjoy the warmth of the fire, which was kept burning through the entire night. Our family, as well as many others, were almost barefooted, and some had to wrap their feet in cloths in order to keep them from freezing and protect them from the sharp points of the frozen ground. This, at best, was very imperfect protection, and often the blood from our feet marked the frozen earth.

In the months and years following the massacre, in hopes of gaining redress and justice for the crimes committed against them in Missouri generally and at Hawn’s Mill specifically, Latter-day Saints later wrote nearly a thousand petitions and affidavits detailing their suffering. Many of those texts documented the incidents of violence and abuse at Hawn’s Mill. Taken together, they comprise some incredibly significant texts in Mormon history.

Along with narrative pamphlets and other histories of the Missouri difficulties, these writings, and the associated efforts to obtain redress and justice from government at all levels, helped create a shared memory for the Latter-day Saint people, who were willing to suffer inequality and endure intense trials for their faith and belief. Men, women, and children demonstrated their faith when they did not deny their religious convictions to save themselves from cruelty and deprivation in the aftermath of the Hawn’s Mill massacre. Their sacrifices, in addition to the sacrifices experienced by all the Latter-day Saints who endured the Missouri violence, should be remembered, understood, and memorialized with compassion and charity.

Tragedy and Truth: What Happened at Hawn’s Mill is the first historical narrative exclusively devoted to explaining why and how the massacre happened and what measures church members took in its aftermath.

But why did the attack occur? Who was involved? And did the Saints at Hawn's Mill disobey Joseph Smith's counsel? These and other telling questions are explained and clarified by four top LDS Church history scholars in this fascinating book devoted exclusively to helping readers understand why and how the massacre at Hawn's Mill happened.