Warren Smith and his wife, Amanda Barnes Smith, were among the first to hear and accept the gospel after The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was organized. They were baptized in 1831 and moved to Kirtland, Ohio, the following year. There they were privileged to participate in many of the early events of Church history, including the building of the Kirtland Temple and the marvelous events surrounding its dedication.

In 1838, the Smiths, along with many other Saints, were forced to leave Kirtland by the enemies of the Church, including many who were former members turned apostate. The exiles became part of the “Kirtland Camp,” a group of just over a hundred families and more than five hundred individuals. The Smiths and their five children left Kirtland in July 1838 and headed west for Adam-ondi-Ahman, Missouri, a distance of more than eight hundred miles.

Unfortunately, although they were hoping to find peace and safety, the Kirtland Camp moved from the proverbial frying pan directly into the fire. By the time the Smiths approached Far West, all of Missouri was in an uproar. As they neared their destination, the Smiths and a few other families were delayed, and the main camp moved on without them.

On October 27, 1838, the situation in Missouri exploded. Governor Lilburn W. Boggs issued his famous order to drive the [Latter-day Saints] from the state or exterminate them. On receiving word of the governor’s order, the Prophet Joseph sent messages to the outlying [Latter-day Saint] settlements and told them to come into Far West for protection.

October 30, 1838

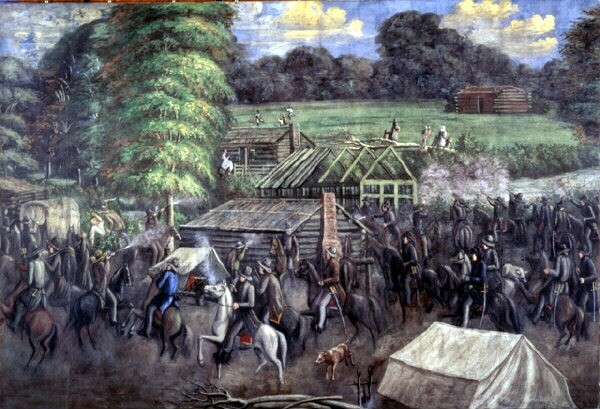

The day after the extermination order was issued, a band of Missourians stopped the small party that included the Smiths and confiscated all their firearms. The following day, October 29, the group stopped at a small settlement just 12 miles east of Far West to rest and repair their equipment. Stopping there proved to be a fateful decision. The town had been founded by a man named Jacob Haun and was called Haun’s Mill. One of those in the Smiths’ group later recorded what happened the next day:

"More than three-fourths of the day had passed in tranquility. . . . The banks of Shoal creek on either side teemed with children sporting and playing, while their mothers were engaged in domestic employments, and their fathers employed in guarding the mills and other property, while others were engaged in gathering in their crops for their winter consumption. The weather was very pleasant, the sun shone clear, all was tranquil, and no one expressed any apprehension of the awful crisis that was near us—even at our doors."1

At about 4:00 p.m., the settlers heard what sounded like distant thunder. Suddenly they saw a band of about 250 men riding hard toward them. As mothers screamed for their children and husbands and fathers came running from the fields, a fusillade of rifle shots erupted. In an instant, all was pandemonium. The women and children ran for the woods, while the men raced for the protection of the blacksmith shop with its thick log walls and heavy door.

Screaming for his three boys to join him, Warren Smith also darted into the blacksmith shop. Alma and Sardius followed. But Willard, the oldest, was thrown back by some invisible force when he tried to pass through the door. He tried again and again, but with the same result, before he raced to a woodpile and dove behind it with bullets flying around him.

The blacksmith shop proved to be a death trap. Although the logs were heavy and thick, there were great cracks between them. The mob dismounted and surrounded the building, then put the muzzles of their guns to the openings and unleashed a withering fire.

Warren went down immediately, gravely wounded. Alma and Sardius crawled beneath the blacksmith’s bellows to escape the gunfire. When the mob broke in, they found Warren Smith crawling toward his boys. They stripped him of his boots, then killed him.

One mob member shoved his rifle under the bellows and fired. The bullet hit Sardius in the head, killing him instantly. Another mobber heard Alma whimpering in terror. He jammed the muzzle of his rifle against the boy’s body and blew the entire hip joint away.

Nor were the women and children spared. As Amanda grabbed her two girls and sprinted for the trees along with the other women, volley after volley was sent in their direction.

When the mob finally retreated, a pall hung over the village. Slowly people began appearing—weeping, dazed, deep in shock. Willard Smith was the first to enter the blacksmith shop. What a terrible thing for a young boy to see. In addition to several other bodies, he found both his father and his brother Sardius dead. Alma, his youngest brother, was nearly unconscious and in terrible agony. He picked him up and took him outside.

“Heavenly Father, What Shall I Do?”

Here is Amanda Smith’s account of what happened that terrible day:

"When the firing had ceased I went back to the scene of the massacre, for there were my husband and three sons, of whose fate I as yet knew nothing. . . . Passing on I came to a scene more terrible still to the mother and wife. Emerging from the blacksmith shop was my eldest son, bearing on his shoulders his little brother Alma. 'Oh! my Alma is dead!' I cried, in anguish. "'No, mother; I think Alma is not dead. But father and brother Sardius are killed!' "What an answer was this to appal me! My husband and son murdered; another little son seemingly mortally wounded; and perhaps before the dreadful night should pass the murderers would return and complete their work! But I could not weep then. The fountain of tears was dry; the heart overburdened with its calamity, and all the mother’s sense absorbed in its anxiety for the precious boy which God alone could save by his miraculous aid. "The entire hip joint of my wounded boy had been shot away. Flesh, hip bone, joint and all had been ploughed out from the muzzle of the gun, which the ruffian placed to the child’s hip through the logs of the shop and deliberately fired. We laid little Alma on a bed in our tent and I examined the wound. It was a ghastly sight. I knew not what to do. It was night now. . . . Yet was I there, all that long, dreadful night, with my dead and my wounded, and none but God as our physician and help. "'Oh my Heavenly Father,' I cried, 'what shall I do? Thou seest my poor wounded boy and knowest my inexperience. Oh, Heavenly Father, direct me what to do!' And then I was directed as by a voice speaking to me. The ashes of our fire was still smouldering. We had been burning the bark of the shag-bark hickory. I was directed to take those ashes and make a lye and put a cloth saturated with it right into the wound. It hurt, but little Alma was too near dead to heed it much. Again and again I saturated the cloth and put it into the hole from which the hip joint had been ploughed, and each time mashed flesh and splinters of bone came away with the cloth; and the wound became as white as chicken’s flesh. "Having done as directed I again prayed to the Lord and was again instructed as distinctly as though a physician had been standing by speaking to me. Near by was a slippery-elm tree. From this I was told to make a slippery-elm poultice and fill the wound with it. My eldest boy was sent to get the slippery-elm from the roots, the poultice was made, and the wound, which took fully a quarter of a yard of linen to cover, so large was it, was properly dressed. It was then I found vent to my feelings in tears, and resigned myself to the anguish of the hour."

Still greatly fearing a return of the mob, the next morning the Saints quickly took stock. The exact number is not known, but there were at least seventeen dead. There was no time to dig graves, so the survivors carried the bodies to a dry hole that was being dug for a well. They hastily threw dirt over the bodies and prepared to leave Haun’s Mill.

“I’ll Never Forsake”

But Alma Smith was not going anywhere. Amanda continues her account:

"I removed the wounded boy to a house, some distance off, the next day, and dressed his hip; the Lord directing me as before. I was reminded that in my husband’s trunk there was a bottle of balsam. This I poured into the wound, greatly soothing Alma’s pain. 'Alma, my child,' I said, 'you believe that the Lord made your hip?' “'Yes, mother.' "'Well, the Lord can make something there in the place of your hip, don’t you believe he can, Alma?' "'Do you think that the Lord can, mother?' inquired the child, in his simplicity. "'Yes, my son,' I replied, 'he has showed it all to me in a vision.'"

That interchange between mother and son is quite astonishing. Her husband and two sons are dead, yet Amanda has not turned bitter. In fact, she teaches her son about the attribute of God’s power. This is a powerful example of how a correct idea of God’s character and attributes strengthens faith.

"Then I laid him comfortably on his face and said: 'Now you lay like that, and don’t move, and the Lord will make you another hip.'

"So Alma laid on his face for five weeks, until he was entirely recovered—a flexible gristle having grown in place of the missing joint and socket, which remains to this day a marvel to physicians. On the day that he walked again I was out of the house fetching a bucket of water, when I heard screams from the children. Running back, in affright, I entered, and there was Alma on the floor, dancing around, and the children screaming in astonishment and joy. "It is now nearly forty years ago, but Alma has never been the least crippled during his life, and he has traveled quite a long period of the time as a missionary of the gospel and a living miracle of the power of God."

During the five weeks in which Alma was recovering, the persecution continued. Far West fell and was ravaged. Joseph and other leaders were dragged off to jail. The Saints were forced to leave. The surviving women of the Haun’s Mill massacre were threatened by the militia who said they would come back and kill them if they didn’t stop praying to God for help.

Amanda describes her reaction to this further difficulty:

"This godless silence was more intolerable than had been that night of the massacre. I could bear it no longer. I pined to hear once more my own voice in petition to my Heaven[ly] Father. I stole down to a corn field, and crawled into a stalk of corn. It was as the temple of the Lord to me at that moment. I prayed aloud and most fervently. When I emerged from the corn a voice spoke to me. It was a voice as plain as I ever hear[d] one. It was no silent, strong impression of the spirit, but a voice, repeating a verse of the Saint’s hymn: "That soul who on Jesus hath leaned for repose, "I cannot, I will not, desert to its foes; "That soul, though all hell shou2ld endeavor to shake, "I’ll never, no never, no never forsake! "From that moment I had no more fear. I felt that nothing could hurt me."

“If God is a loving God as you say,” some might ask, “why did he allow Amanda’s husband and two of her boys to be killed in the first place? Why didn’t he warn them not to stop at Haun’s Mill?”

Those are difficult questions, and we don’t have easy answers for them except to say that the Lord does not always reveal His purposes to us. As He has said, “For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways” (Isaiah 55:8).

The better question is this: Where did Amanda Smith find such astonishing faith and courage? It came directly from her unshakable faith in God’s power to heal, and her belief that He had not forgotten her, even in such a terrible hour.

Amanda Smith’s story is a powerful example of the truthfulness of what Joseph Smith taught in the School of the Prophets about faith and having a knowledge of God. This is what sustained Amanda Smith through a terrible tragedy. This is what allowed her to say, “From that moment on I had no more fear.”

Lead image by C.C.A. Christensen, Wikimedia Commons

Notes

1. Joseph Young, in Joseph Smith, History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 7 vols., edited by B. H. Roberts (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1932–51), 3:184.

2. “Amanda Smith,” in Andrew Jenson, LDS Biographical Encyclopedia, 4 vols. (Salt Lake City: Andrew Jenson History Company, 1914), 2:796; paragraphing modernized. Some information also comes from the entry on Willard Smith, 1:473.

As Latter-day Saints, we know God exists, but sometimes we may wonder, “Heavenly Father, are you really there for me?”

When trials seem beyond our ability to bear, some people lose their spiritual bearings, while others are made even stronger. How can we strengthen our faith and deepen our testimony to the point that we can endure whatever life holds in store for us and emerge stronger than before?

In this unique book,Gerald N. Lund shows how having a correct idea of God's character, perfections, and attributes is essential to our ability to strengthen our faith and develop our testimony.

He also reminds us of how much God loves His children and that He “delights” to bless us, especially when we are striving to do His will. As and example, Elder Lund introduces the idea of a divine signature: “Sometimes blessings come in such an unusual manner and with such precise timing that they accomplish something in addition to blessing us. They so clearly confirm the reality of God's existence that they buoy us up in times of trials.”

Throughout the book, Elder Lund relates story after story — some from Church history, some from his own life, and some from acquaintances — that illustrate the inspiring and life-changing insights he shares.

This book is a powerful blend of personal reflection and deep doctrine that will help us identify the tender mercies and “divine signatures” that abound in our own lives and which will lead us closer to God.