In A. J. Russell's iconic photograph of the celebration following the driving of the golden spike, Samuel S. Montague, chief engineer of the Central Pacific Railroad, is shaking hands with Grenville M. Dodge, chief engineer of the Union Pacific Railroad. Somewhere in the crowd is Leland Stanford, who first missed and then tapped the golden spike into a pre-drilled hole in a special railroad tie made of polished California laurel.

One person most likely not in the photograph was William Hayward, a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and an immigrant from England. Employed by the Union Pacific Railroad Company for several months as a cook, he was busy cooking a banquet for the railroad officials.

Early Life

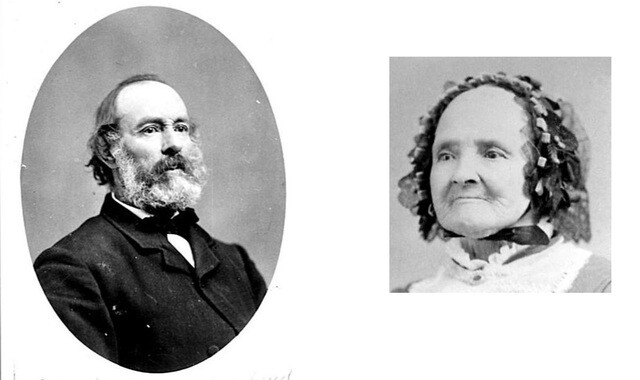

Born in England in 1817, Hayward became a professional cook, and on January 20, 1837, he joined the King's Navy, eventually serving as deputy commissaries general for 16 years, according to The History of William Hayward by ReVon Hayward Porter. In March of 1837, he married Ruth Hughes. They became parents of two daughters, Hannah and Emma. Emma died as a child but Hannah grew to adulthood and became the mother of 13 children. With Hayward often away at sea and stationed at various ports, his grandson Claude Vincent Baker said his mother, Hannah, was seven years old before she really got to know her father.

In October of 1841, while stationed at the port of Jaffa, Hayward met an American named Orson Hyde. As recounted in the book Orson Hyde: The Olive Branch of Israel:

"William Hayward, a British seaman, also filled the Lord's purpose of becoming a witness to Orson's mission. Twenty-four years old, a big man with curly red hair, and a cook on a British ship, he spent leisure hours in Jerusalem during his vessel's layover in the Jaffa port. In Jerusalem he met Orson Hyde and listened to him tell of the rites he performed on the Mount of Olives [when he dedicated the land of Palestine for the return of the Jews]."

His great-granddaughter Erma Bean Chadwick wrote, "At the time, William was puzzled at the proceedings." Not until several years later did he understand the full import of his meeting with Orson Hyde there in Jerusalem. "[He] felt he had been especially privileged to be in the Holy Land at the same time as Apostle Hyde" (Orson Hyde: The Olive Branch of Israel, p. 143).

Joining the Church

Porter stated in her history "[Hayward loved] the theater and fine arts and would much rather attend them than any of the churches he had been [visiting]. [He felt] that none of them [gave] him the satisfaction he [sought]." His wife, Ruth, however, was a religious woman and wanted to go to church with him, "so they made a compromise. He promised her that he would accompany her to church and she promised him that she would attend the theater with him."

In 1849, Hayward returned home to find that Ruth and Hannah had joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Porter wrote:

"He listened to the new word of truth from the Mormon missionaries and became more interested than he had ever been in any religion . . . He went again and again to hear more of this wonderful Gospel and was converted. He was baptized on April 20, 1851 by Thomas Wilkins."

Now united in their faith, the Haywards began to save and prepare to go to America and join with the Saints in the valley of the Great Salt Lake. After making their way to Iowa, the Haywards were assigned to a handcart company, and William, Ruth, and Hannah (age 14) left their luggage behind at Council Bluffs and walked across the plains, arriving in Salt Lake City on October 16, 1853. They lived in Salt Lake City for a time before moving to Ogden, where Hannah, now age 16, met and married William George Baker on November 25, 1855.

In a brief sketch of the life of Hannah Hayward Baker as told by her son, Claude Vincent Baker, during the fall and winter of 1857 to 1858, Ruth and Hannah were left to harvest and store their crops as best they could while Hayward and his son-in-law were stationed in Echo Canyon, blocking the advance of Johnson's Army into the Salt Lake Valley. "[Ruth] had kindling arranged in one corner of their home, so it could be easily set on fire if the army came. When the people were asked to move south while the army passed through [the Haywards and Bakers] loaded their wagon and went along." They eventually settled in the new community of Richfield.

"During the grasshopper famine," Porter writes, "[they] went barefoot, were poorly clothed and often hungry: too proud to beg, too poor to eat. At one time they were without bread for nine days . . . [and] lived on green roots and pig weeds. At this time, Ruth emptied a pin cushion she had brought from England that was filled with bran and baked a bran cake for them . . . it tasted good."

Saved by a Prompting

Porter wrote:

"President [Brigham] Young gave William a blessing in the St. George Temple promising him the gift of healing and answers to prayers. . . . One time the Haywards were traveling from Moroni to Nephi. They were obliged to make camp in Salt Creek [now Nephi] Canyon. Another family had camped at the same place. After all had retired and everything seemed peaceful, William woke up. He immediately woke the rest of the camp and told them he had a warning of danger. They must move on. The rest of the company decided not to go, but William took his family and left. During the night the rest of the camp was murdered by . . . Indians."

Just as Wilford Woodruff was warned to move his carriage, thus saving his life and the lives of his wife and child, William was warned by the whisperings of the Spirit. His obedience saved his life and the lives of his family members who were with him. It didn't matter that he was not destined to become the prophet. Heavenly Father will guide and protect His humble servants no matter their station in life.

Porter states, "William was often called upon to administer to the sick. He had a very firm testimony of the gospel. . . Because of his former experience as cook he was often put in charge of banquets when distinguished guests were present or when there were numerous people in attendance."

In her history, Chadwick wrote:

"Ruth's health was very poor in her later years and William was very concerned and thoughtful concerning her comfort. He formed the habit of serving her breakfast in bed each morning . . . Nothing was ever too much trouble for him to do for his children. He would pick huge bouquets of lilacs for them and say 'God gave them to me to make others happy.'"

Chadwick wrote that after William's death, Ruth spent her last years in the home of her daughter, Hannah. Hannah's children and grandchildren continued the tradition he began of serving her breakfast in bed. "It was considered a real honor to be the one chosen to carry her breakfast to her . . . The children adored her." When she died on October 13, 1904, in Richfield, she was the oldest citizen of Richfield.

And as for cooking the banquet for the historic driving of the Golden Spike? His great-granddaughter, Mable Baker Haycock wrote in her history William Hayward, "For [cooking the banquet] . . . he was given a choice of a $10 gold piece or a large wall clock. He accepted the clock. As long as he lived it gave him service. At his death his daughter received it." Hannah's grandson of Brigham City, Utah, eventually inherited the clock which was still running "with the correct time," when he died, childless, in 1961.