On an island divided by political and religious borders, about 8,000 plucky Irish Latter-day Saints1 have discovered a way to find unity through the gospel of Jesus Christ.

The message of the Restoration first came to Ireland in the spring of 1840, a decade after the organization of the Church. In May, the first missionary to arrive was Reuben Hedlock, who spent three days in Belfast before moving on to Paisley, Scotland. While in Belfast, Hedlock made a few contacts, observed the budding though divided city, and described its segregated populace as he passed through the sorrowful streets of Northern Ireland: “This is a fine flourishing town, containing about 54,000 inhabitants. Here I met … the rich enjoying their abundance and the poor in rags begging for a morsel of food to sustain life. I had never before witnessed such scenes of suffering.”2 He queried, “Has the Gospel of Jesus Christ lost its power … so that one part of the human family must drag out a miserable existence, and die in wretchedness and want, while the other can live in pride and plenty all their days?”3

A Prophecy Fulfilled

By this time, Apostle John Taylor had a branch of the Church established in Liverpool, where one out of seven of the city’s inhabitants were from Ireland. Two of the migrant Irish converts in Great Britain during this era were James McGuffie and William Black, who sailed with Elder Taylor for Ireland July 27, 1840 as missionaries.4 Because McGuffie had contacts in the northern town of Newry, the three elders went there first. Arriving the following day, McGuffie immediately made arrangements at the local courthouse for a “bell-man” to ring out the message of Elder Taylor’s forthcoming sermon in Sessions Hall that very night. Notwithstanding little time to advertise, that first Latter-day Saint public sermon in Ireland drew a crowd of more than 600, who came to hear the Latter-day Saint apostle expound the doctrines of the Restoration.5

The following evening, Elder Taylor again preached in Sessions Hall, though few attended. Therefore, apparently they were planning on leaving town the following day. Later that night, Elder Taylor had a vision in which he saw a man who asked him to stay in Newry because he would like to hear Elder Taylor preach. The next morning, as the three missionaries were leaving town, the man from Elder Taylor’s dream, Thomas Tate, whom Elder Taylor had first met in Liverpool, prophesying that Tate would be the first person baptized in Ireland, approached them and asked them to remain.6 Instead, however, Tate traveled a few miles with the elders, where Elder Taylor preached in a barn. The following day, as the group approached the small village of Loughbrickland, with a body of water nearby, Tate said to Taylor, “There is water, what doth hinder me from being baptized?”7 The missionaries immediately stopped, and Elder Taylor baptized Tate, fulfilling the prophecy made in Liverpool.

Challenges and Triumphs

Converts such as Tate were hard to come by, though a few trickled in as the years passed. One major obstacle during the mid-1840s was the devastating Irish famine (1845–1847), which left hundreds of thousands starving and destitute. The missionaries faced both challenges and opportunities during this period, as religious controversy was prevalent. Elder Paul Harrison described his labors among his people: “The Irish are … very shrewd, and can comprehend anything you talk about to them. … It takes a man with a depth of intellect to converse with them, about religious matters, especially when the views of the parties differ.” Harrison added, “If an elder with depth of intellect … could be sent there, many—very many—would ere long be added to our church.”8 Though capable elders were being sent, the pangs of physical hunger from Ireland’s famine made it difficult for most to focus on the gospel message, and the country remained physically and spiritually famished for some time.

As the desolation subsided and the Irish people again were able to focus on spirituality, Franklin D. Richards, president of the British Mission, announced the return of the missionaries to Ireland. He stated, “The Saints have looked upon Ireland with pity; and wishfully wondered when her noble sons and daughters would be aroused from their slumber of ages and come to the help of the Lord … and engage in the establishment of Zion in the last days. … It is earnestly hoped the present may prove the dawning of a better day to the seed of promise in the Emerald Isle.”9

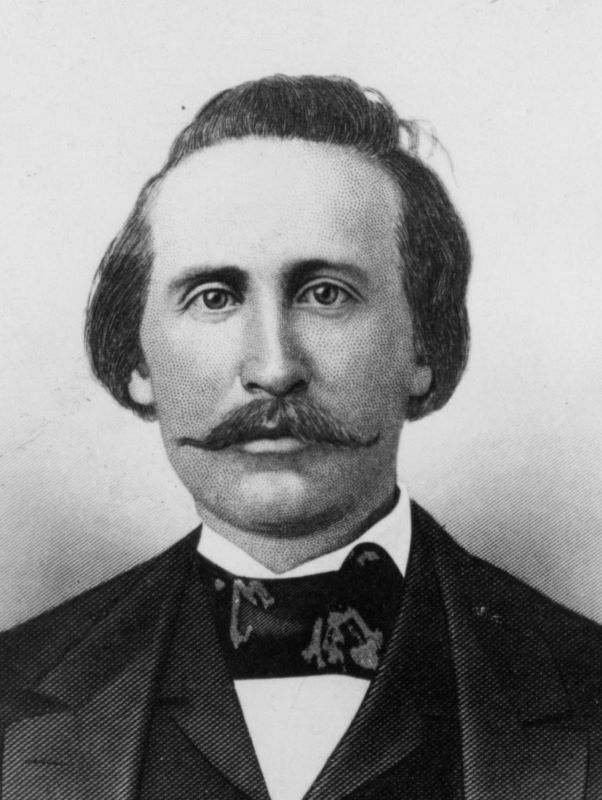

One Irishman who spiritually awoke and led the way for a brighter day in Ireland was James B. Ferguson, appointed as the presiding elder of a small band of missionaries sent to Emerald Isle in 1854. During Ferguson’s era, nearly 100 Irish Saints joined the Church, and by 1856, Church membership exceeded 200.10 Ferguson’s companion, John D. T. McAllister, witnessed Ferguson’s enthusiasm when the Belfast Branch took an excursion to nearby Cave Hill. McAllister explained that when the Saints reached the summit, Elder Ferguson “led off three times [with] three cheers for the advancement of ‘Mormonism’ in Ireland. The brothers and sisters joined, and we made it echo again and again.”11

Living the Gospel in Divided Modern Ireland

Like Ferguson, modern-day Latter-day Saints in Ireland are advancing the cause of the Church in their native land and sending reverberations to their fellow Saints and countrymen. One such catalytic Latter-day Saint athlete is 32-year-old Jason Smyth, who now lives in Dunmurry, just outside Belfast. In 2014, Smyth, a legally blind paralympian sprinter, set world records in both the 100 and 200 meter races.12 In the Tokyo 2020 Paralympics he took gold in the Men's 100 meter. He attributes the gospel as a major factor in his success. Smyth stated:

I think my faith has been a massive reason of why I've been as successful as I have in my running. For me, the quality of attributes, the characteristics that follow that turn a talent into success, a lot of them align with the things that we’re taught in the gospel—the principles of working hard, commitment. … I’m not going to be the same as somebody else, but it’s measured by you being the best that you can, and I think that’s what the gospel brings me. It’s this understanding and this knowledge of those things … a belief, a knowledge that everything will work out if I do everything that I can and am satisfied with that. You can physically see the training, but what you actually can’t see in anybody is what’s going on underneath—who they are as a person, what they stand for, the confidence that can bring. And for me, that is probably one of my biggest strengths that I find I have over other athletes is the gospel in my life.13

Due to his immense success, Smyth has also had many occasions to share his faith in public settings, and he has taken advantage of such opportunities. He has discovered that people in Ireland are “very, very respectful of members of the Church.” Smyth states, “People respect me for what I stand for. For having morals. … When I’m interviewed by the media, my faith comes up. … When you’re in sport … at a high level, people tend to want to know everything. … What motivates you, and for me, a big part of that is the gospel. … People are very positive toward me and very much wanting to know more.”14

Smyth, who was raised in “Derry” (Londonderry, Northern Ireland), noted that as a Latter-day Saint, he chooses not to get caught up in the political issues of whether one of his fellow countrymen leans toward being more British (Northern Ireland) than Irish (Republic of Ireland). He also avoids the issues stemming from a century-long debate between the Protestants and the Catholics. He stands in a position outside this struggle as a peacemaker. In his youth, he even recalls occasions when a few Church members distinguished themselves as a Protestant or Catholic Latter-day Saint, but Smyth notes that today he believes most just consider themselves Saints with the same cause.15

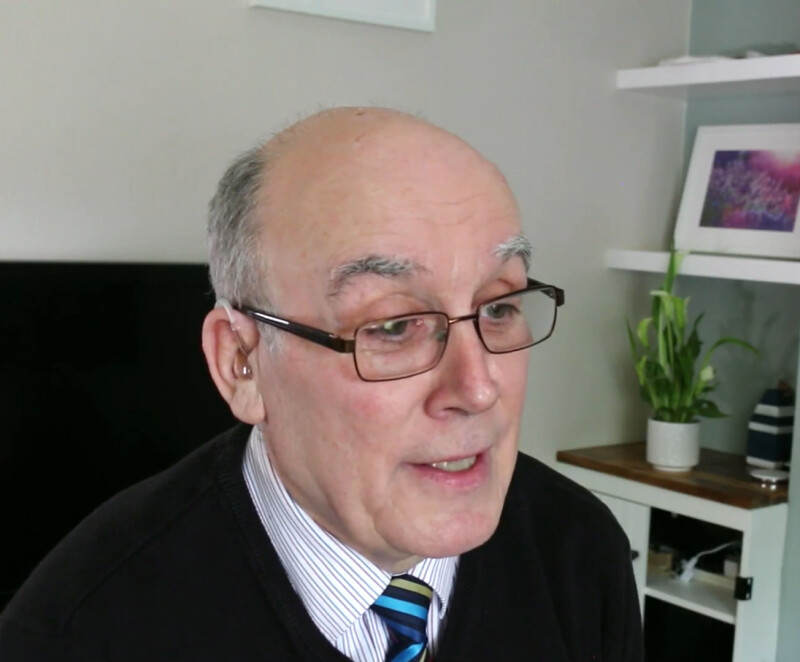

Another active Irish Saint making a difference is John Connolly of Dublin, the capital of the Republic of Ireland. Connolly, currently the director of Church public affairs for Ireland, keeps busy looking for common ground as he works with interfaith community activities where such issues as homelessness and religious freedom are addressed. He believes that today “there is more opportunity to work with people of faith than perhaps there was in past times” because people are, in his words, “pulling together.” Within the Church itself, Connolly observes that the Saints resist succumbing to dividing tensions.

He recalled an occasion when Elder Neal A. Maxwell dedicated Ireland for the preaching of the gospel (October 23, 1985) at Loughbrickland, where the first Latter-day Saint baptism in Ireland occurred. Records kept on that occasion note that Elder Maxwell prayed: “Where there has been strife, may there be peace … for thy cause to move forward as never before. May thy soothing spirit, Father, encourage reconciliation.”16 Connolly came away from the experience sensing that where there were borders and divisions in the eyes of mortals, God saw all of His children as one.17

One recently appointed to gather and remind the Irish Saints of their great Latter-day Saint history and union is Thomas Holton, also from Dublin. Holton has been called as the Church history specialist for the Republic of Ireland. A convert who joined the Church several decades ago, Holton hopes to “encourage the recording and remembering of the rich history of the Church in Ireland.”18 Currently, that statistical history consists of 2 stakes, 1 district, 23 congregations, and several family history centers sprinkled throughout the island where Church members assemble and their fellow countrymen are invited to attend.19 Though few in number, the Irish Saints are a “covenant people of the Lord … armed with righteousness and with the power of God” (1 Nephi 14:14). Their pluck, or spirited and determined courage to adhere to the teachings of the gospel of Jesus Christ, not only impacts each other but advances goodness into communities and neighborhoods wherever they reside.

▶ You may also like: Osmondmania: The Latter-day Saint family who took the UK by storm as ‘musical missionaries’

To learn more about what it is like living as a Latter-day Saint in Ireland, watch interviews with Smyth; Connolly; Connolly's wife, Eileen; and two other Irish members, who share their conversion stories, in the videos below.

Interviews conducted by Fred E. Woods and Martin Andersen in 2019.

Jason Smyth

John Connolly

Eileen Connolly

Bernard O'Farrell

Eric Bowyer

Notes

1. A number of these 8,000 Church members are from either the third or fourth generations. See https://newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org/facts-and-statistics/country/ireland accessed September 25, 2019. John Connolly, Director of Church Public Affairs public for Ireland noted some Irishmen would side politically with the British (termed a unionist) and others would consider themselves Irish (defined as a nationalist), while some a mixture of both British and Irish. He noted, “Generally speaking, Protestants in Northern Ireland are unionist and Catholics are nationalist. In the Republic [southern region], people’s religious belief does not affect their sense of Irishness.” (John Connolly email to Fred E. Woods, September 28, 2019).

2. Brent Barlow, “History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Ireland Since 1840,” M.A. Thesis, Brigham Young University, 1968, Provo, Utah, 17. The author acknowledges the important sources Barlow has gleaned which has provided assistance to easily navigate primary sources in the early part of this article.

3. Reuben Hedlock, “Sketch of the Travel and Ministry of Elder R. Hedlock, The Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star, vol. 2, no. 6 (October 1841), 92.

4. Ibid., 85-86.

5. Barlow, “History of the Church in Ireland,” 18.

6. B. H. Roberts, The Life of John Taylor (Salt Lake City, Utah: Bookcraft, 1963), 84–85.

7. Ibid., 86.

8. Paul Harrison, “A Prophecy,” The Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star, vol. 10, no. 18 (September 15, 1848), 286.

9. F. D. Richards, “Ireland,” The Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star, vol. 12, no. 16 (1850), 254.

10. Barlow, “History of the Church . . . in Ireland,” 47–48.

11. John D. T. McAllister, “Home Correspondence,” The Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star, vol. 17, no. 21 (May 26, 1855), 334–35.

12. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jason_Smyth, accessed September 25, 2019.

13. Interview of Jason Smyth by Fred E. Woods and Martin Andersen, May 7, 2019, Dunmurry, Northern Ireland.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid. John Connolly, who graciously reviewed this article, noted on this point, “Personally, I have NEVER come across the notion of ‘Catholic’ or ‘Protestant’ Latter-day Saints. There are of course Latter-day Saints of both unionist and nationalist opinion.” (John Connolly email to Fred E. Woods, September 28, 2019).

16. “Ireland Dedicated for Proselyting,”Ensign (February 1986), 76.