Photo of Sam Cowley from keepapitchinin.org

What do notorious gangsters John Dillinger and Lester Gillis (aka “Baby Face Nelson”) have to do with the LDS Church? Simple: they were tracked and ultimately killed thanks to the action of a Mormon government agent—an action that secured his billing as a national hero.

Sam Cowley was launched into the workforce just in time to witness “Black Tuesday,” the crash of the stock market, and the birth of the Great Depression—not exactly the best time for a newly minted attorney to find a job.

Casting his net far and wide, he ended up in Washington, signing on with a novice investigative bureau in the US Justice Department that would later expand into the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

Cowley considered the bureau a temporary stop on his way back home. His real aspiration was to land a job practicing law in Utah. But he was promoted so rapidly by the bureau that he decided to stay. Cowley was a soft-spoken, mild-mannered employee who preferred to shun the spotlight—scarcely the kind of guy you’d expect to be involved in a shootout with the most notorious gangsters in the nation. Those humble traits, however, followed him throughout his career with the bureau, as Deseret News reporter Matthew Brown noted in 2009:

Descriptions of agent Cowley give the impression that he likely would have preferred not being mentioned at all. By most accounts, Cowley avoided the press and, as a result, rarely got the credit he deserved in helping stamp out America’s first great crime wave. His background and demeanor were also incongruous with a popularized image created in films of a tough and gun-toting G-man.

You’d think it would take decades for a guy like Sam Cowley to go from being a desk jockey to a gun-toting special agent bent on finishing each assignment he was given. Not so. FBI reports noted that he was “absolutely reliable” and “utterly dependable.” When he was promoted to the rank of inspector only five years after being hired by the bureau, he got the call that would change his life: FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover wanted to see him.

Hoover had a simple command for Sam Cowley: Find John Dillinger. Do whatever it takes. Go wherever you need to go.

His assignment was to survey the situation and report back with some recommendations. But, according to Bryan Burrough, Cowley’s biographer, Cowley dug in his heels in Chicago. Instead of just observing and writing up some sort of report, “Cowley took charge, reorganizing resources, sorting out informants, refining leads, studying the criminals he was pursuing, and planning the stakeouts that would lead to their capture.”

Cowley’s investigative work resulted in the tip that John Dillinger was planning on attending a movie, Manhattan Melodrama, in Chicago on the night of June 22, 1934.

At exactly 8:30 p.m., Dillinger and two female companions—Polly Hamilton and Anna Sage—strolled into the Biograph Theater without a care in the world.

Cowley double-checked to make sure all possible escape routes were cut off. They were. He could virtually taste victory.

When Dillinger realized there were agents waiting outside the theater, he tried to escape. But was killed in a hail of bullets fired by Cowley and his men before his hand could even clutch his weapon.

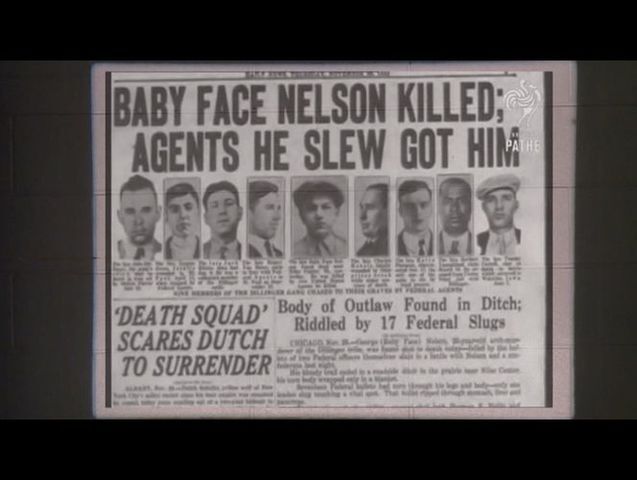

With Dillinger’s crimes brought to a halt, Hoover placed the ultimate confidence in Cowley by asking him to track down Dillinger’s maniacal coconspirator, Lester Gillis—better known by his alias, “Baby Face Nelson.” Nelson had joined forces with Dillinger in terrorizing the country and, at the young age of 25, had spent more than half his life in crime. According to Burrough, Hoover gave Cowley unrestricted power, allowing him whatever he needed to hunt down Baby Face Nelson and others designated by the FBI as public enemies.

Photo of Baby Face Nelson

So Cowley rounded up every spare agent in a three-state area and set out to capture Baby Face Nelson.

On November 27, Nelson was driving down Route 14 toward Fox River Grove, Illinois, with his wife, Helen Gillis, and a two-bit criminal named John Paul Chase. A pair of federal agents passed Nelson going the other direction; recognizing him in his black Ford, they burned up the asphalt with the fastest U-turn ever negotiated. Nelson, also recognizing the agents, made a quick turnaround of his own and started chasing them.

Nelson’s weapon shattered the agents’ windshield, at which point they floored it and drove off the road into a field—but not before getting off a shot that went straight into Nelson’s radiator. The big Ford overheated and sputtered to a stop, completely disabled.

At that moment, Cowley and another agent, Herman E. Hollis, were driving up the road toward Barrington. In rapid-fire succession, Cowley recognized his fellow agents’ bullet-ridden car hobbling across the field and Nelson’s big black Ford, license plate 639–578. Cowley immediately pulled over, after which he and Hollis jumped out and took cover behind their car. Hollis was armed with a shotgun; Cowley had a submachine gun.

An epic shootout followed.

At one point, Nelson’s rifle jammed. Scarcely losing a beat, he picked up a Thompson machine gun and resumed his attack on Hollis and Cowley. Although he was repeatedly shot by both Hollis and Cowley, Nelson made a final desperate attempt to cross the road and shot both agents. Hollis managed to fire 10 times before he fell dead from a bullet in the forehead. Cowley got off more than 50 shots before he fell wounded, too weak to continue and two bullets lodged in his abdomen.

A nearby witness rushed to Cowley’s side as soon as Nelson made his hurried escape in Cowley’s car. Cowley managed to tell the witness that he was a federal officer and that he needed help—but pled with the man to take care of his partner first.

Cowley was rushed to a local hospital but refused surgeries until he could talk to his partner from the Dillinger case, Melvin Horace Purvis Jr., and identify Baby Face Nelson as the man who had wounded him and killed Hollis. At one point, Cowley even told a doctor that he needed to talk to Purvis before he died.

Early the next morning, he was able to talk to Purvis and several other superiors; he clearly identified Baby Face Nelson and John Paul Chase but said he did not know the woman who was in the car with them. That important job completed, Samuel P. Cowley died. He was 35 years old and had been with the FBI for a mere five years.

Later the same day, federal officials found the body of Baby Face Nelson in a ditch in front of a cemetery in Skokie. Nelson’s body was riddled with 17 bullets from Cowley’s gun. Two days later, officials apprehended Helen Gillis and took her into custody. A month later, John Paul Chase was also arrested.

Samuel P. Cowley’s body was flown back to Utah, his home state, for his funeral. There the man who wanted only to stay in the background lay in the Capitol rotunda in Utah, surrounded by an honor guard. Thousands filed by to pay their respects—including President George Albert Smith and all the members of the Quorum of the Twelve. His funeral was held in the Assembly Hall on Temple Square, where President Smith, Elder John A. Widtsoe, US Senator Elbert Thomas, and Utah Governor Henry H. Blood delivered eulogies, and a bevy of church, civic, and political leaders gathered to pay tribute.

The man who shied away from headlines was hailed a hero in every newspaper in the state. His fame even spread nationally, with the United Press, the Associated Press, and the New York Times all weighing in on his relentless pursuit of criminals. And his influence would not be soon forgotten. FBI Assistant Director Harold Nathan eulogized Cowley by saying, “As generations of new agents come into our service, they will be told of the life and death of Sam Cowley. He will become a tradition. He will have attained earthly immortality.” Director Hoover himself also held up Cowley as a hero and the epitome of an FBI agent.

Cowley is buried in Wasatch Lawn Memorial Park in Salt Lake City, where his father dedicated his grave.

Lead image from iStock