I used to really struggle reading Isaiah. When I was 13 years old and couldn’t sleep on Christmas Eve, I read Isaiah to help me drift off. (And no, I’m not making that up!) When I was a seminary teacher, I tried to avoid teaching Isaiah as much as possible; for example, if I was teaching 1 Nephi 20–22, I would spend all my time on chapter 22, since chapters 20–21 are quotes of Isaiah.

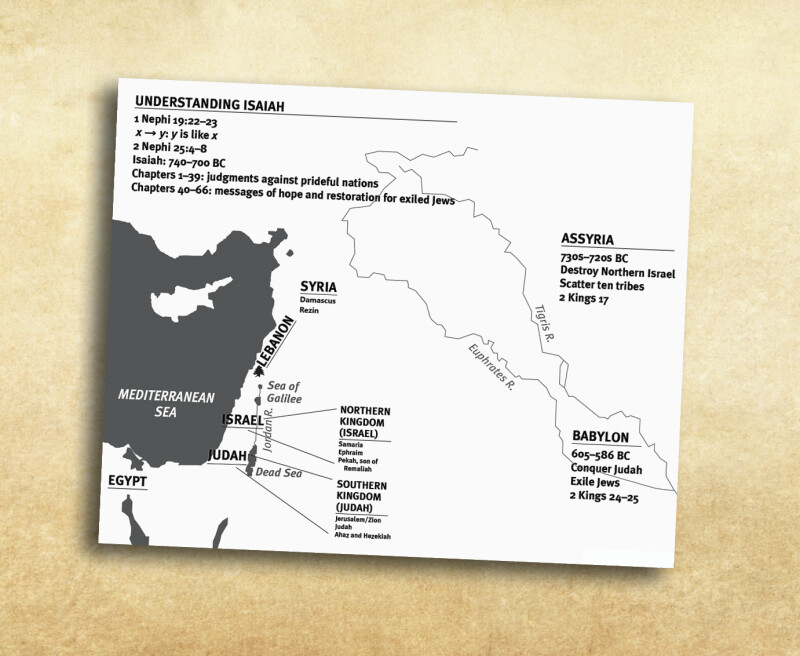

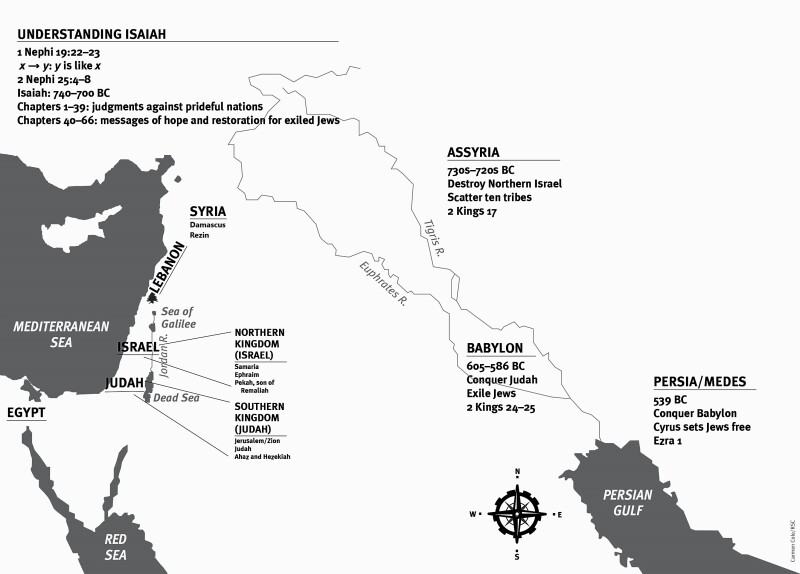

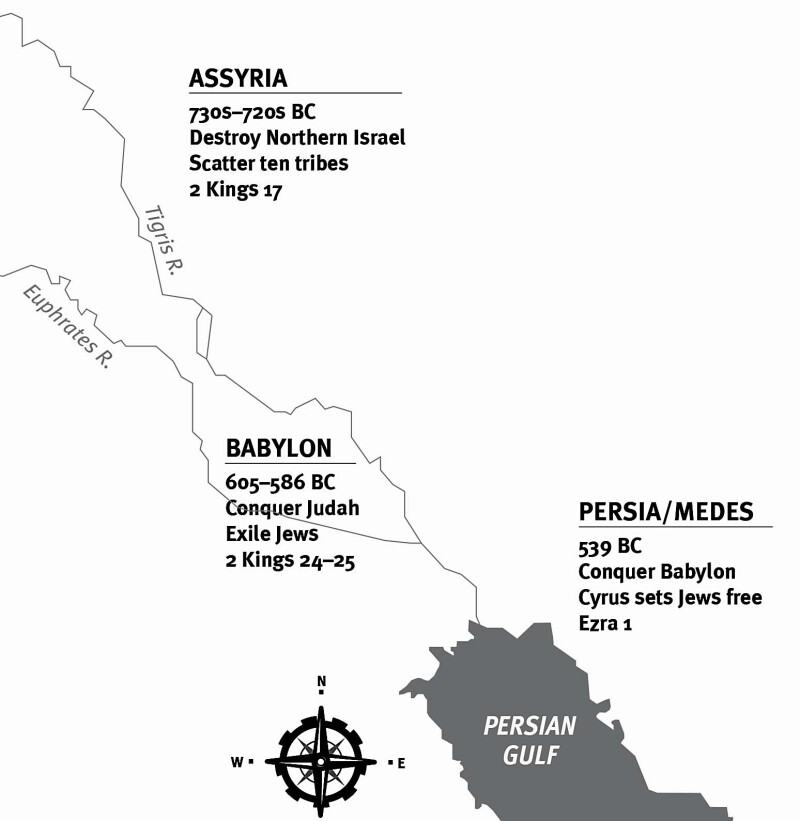

But all that changed several years ago, when I was fortunate enough to sit across the aisle from my colleague Matt Grey on a flight to Chicago. Matt teaches ancient scripture at BYU, and on that occasion he sketched out what he called the “Isaiah Map,” showing me how on just one page you could summarize and simplify a lot of history and geography that is important for understanding Isaiah. This Isaiah Map completely changed the way I read Isaiah.

In this article, I’ll walk you through this map and show how it can help us make sense of Isaiah’s words. First, let’s look at the map as a whole, and then we’ll zoom in on individual sections.

⟶ Download a copy of the Isaiah Map here.

The Isaiah Map

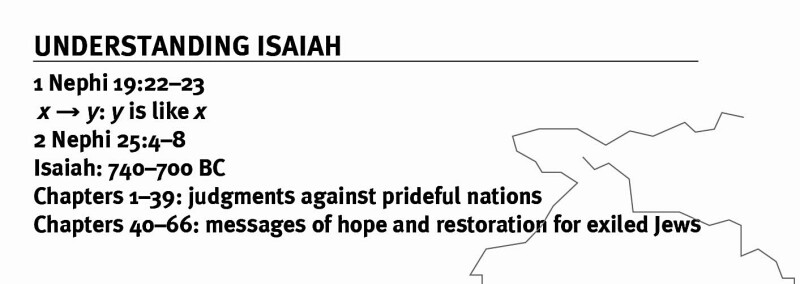

As we zoom in on the upper-left hand corner of the map, we find a couple of foundational passages:

1 Nephi 19:22–23. In these verses, Nephi states, “I, Nephi, … did read many things to them, which were engraven upon the plates of brass, that they might know concerning the doings of the Lord in other lands, among people of old. … I did read unto them that which was written by the prophet Isaiah; for I did liken all scriptures unto us, that it might be for our profit and learning.” Note that Nephi prefaces his Isaiah quotations by saying that Isaiah’s words are about “people of old” in “other lands.” Although Isaiah can—and should—be likened to our day, we shouldn’t be surprised to learn that his writings specifically pertained to the people of his day and his part of the world.

x ⟶ y: y is like x. The concept of likening is listed second in the upper-left corner. We can think of likening as the process of saying “x ⟶ y” or “y is like x.” When studying Isaiah (and other scripture), we perhaps too frequently focus on the modern application (the y), before understanding the original context of the scriptures (the x). In this case, the x is the historical events that Isaiah addressed in his writings. As we better understand the x—the original historical context—we’ll be better able to liken Isaiah’s words to our lives. Some of the important context of Isaiah is included in the map and will be explained later.

▶You may also like: Does the Old Testament sometimes seem bizarre? This study strategy can make all the difference

2 Nephi 25:4–8. The second passage in the upper left-hand corner is 2 Nephi 25:4–8. After extensively quoting from Isaiah, Nephi provides some important keys for understanding Isaiah’s words. Nephi says, “I … have dwelt at Jerusalem, wherefore I know concerning the regions round about; and I have made mention unto my children concerning the judgments of God, which hath come to pass among the Jews, … according to all that which Isaiah hath spoken” (2 Nephi 25:6). This verse is included on the map to remind us that understanding both the geography (“the regions round about”) and the contemporary ancient history (“the judgments of God”) are essential to understanding Isaiah.

Let’s use a modern example to show how important it is to understand geography and contemporary history when reading by using trying to interpret the following sentence: “Biden is going to the Big Apple to meet with the UN. He is angry at Beijing.” Most of us can understand this hypothetical sentence. But would a person living 2,500 years from now understand it? This statement, written in the language of our time, could be very confusing to people not familiar with the geography and politics of the early twenty-first century. Similarly, learning a little about the history and geography of Isaiah’s time will help us better understand Isaiah’s words.

Let’s observe a few other details from the upper-left corner of the Isaiah Map:

Isaiah: 740–700 BC. Isaiah prophesied around 740–700 BC. This helps us connect Isaiah’s writings with contemporary events of his lifetime.

Messages of chapters 1–39 and chapters 40–66. Notice the final two lines in this corner of the map. Although I acknowledge this is a simplification of the situation, we can think of the book of Isaiah as having at least two major divisions. The first key theme, in Isaiah 1–39, is “Judgments against prideful nations.” A second key theme, emphasized in Isaiah 40–66, is “Messages of hope and restoration for exiled Jews.” Watching for these themes can orient us when a chapter seems confusing.

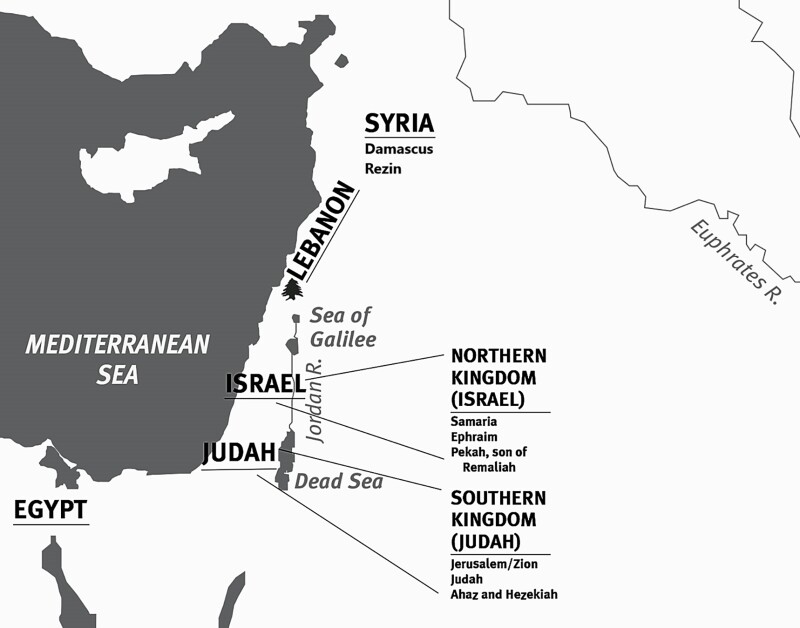

Now let’s look at the rest of the information on the left-hand portion of the map. Between about 1050 and 950 BC, the twelve tribes of Israel were united under the reigns of kings Saul, David, and Solomon, in that order. But after King Solomon’s death, the twelve tribes divided into two kingdoms. The Northern Kingdom, often referred to as Israel, was made up of ten tribes, and the Southern Kingdom, also called Judah, was made up of two tribes: Judah and Benjamin.

The map provides facts about each of these two kingdoms:

Israel

- Israel’s capital was Samaria.

- Israel’s dominant tribe was Ephraim.

- One of Israel’s kings in Isaiah’s time was Pekah, the son of Remaliah.

Judah

- Judah’s capital city was Jerusalem (also referred to as Zion).

- Judah’s principal tribe was Judah.

- Judah had a series of Davidic kings. Its two most important kings during Isaiah’s lifetime were Ahaz and Hezekiah.

As the map shows, further north of Israel was Syria, with its capital city of Damascus and its king, Rezin. All this information can help us understand Isaiah because he writes explicitly about Ahaz, Pekah, and Rezin (see Isaiah 7–8). Knowing their names will help us understand the context of Isaiah’s message in chapters where he focuses on these countries.

Now let’s turn to the right-hand portion of the map:

Assyria. Between 730 and 530 BC, there were three major superpowers in the region. The first was Assyria, which between 730 and 720 BC destroyed the kingdom of Israel and carried away its inhabitants (see 2 Kings 17). Assyria’s conquering of Israel took place during Isaiah’s ministry; thus we should not be surprised that this is an important theme in his writings.

Babylon. In approximately 625 BC, Babylon, a new superpower, defeated Assyria; and between 605 and 586 BC, Babylon made multiple incursions into the Southern Kingdom, eventually resulting in the destruction of Jerusalem (see 2 Kings 24–25). This is the destruction that Lehi was prophesying about when his family left Jerusalem (see 1 Nephi 1:13). As part of its conquest, Babylon carried some of the Jews, including Judah, into exile.

Note that while the ten tribes of the Northern Kingdom were scattered and lost to history after being conquered, those in the Southern Kingdom (primarily Judah) continued to maintain their religious identity during their time of exile in Babylon and afterward. The Lord’s message of comfort to the Jews in Babylonian captivity is a key part of Isaiah’s message (remember the second theme in the upper-left corner of the map?).

Persia. The third and final superpower on the map is Persia. In 539 BC, Cyrus, the king of Persia, defeated Babylon and allowed the Jews to return to their homeland if they chose (see Ezra 1). Themes of Persia conquering Babylon and setting the Jews free appear throughout Isaiah’s writings (for example, see Isaiah 48–52).

▶ You may also like: One simple tool to help you get so much more out of Isaiah

Using the Map

Let’s look at one example of how the Isaiah Map can help us understand Isaiah’s words. In Isaiah 49, the Lord extends a powerful message: “I will lift up mine hand to the Gentiles, and set up my standard to the people: and they shall bring thy sons in their arms, and thy daughters shall be carried upon their shoulders” (Isaiah 49:22).

By using the Isaiah Map, we see that Isaiah 49 falls within the section with the theme “Messages of hope for exiled Jews.” In this context, Isaiah is prophesying that a group of Gentiles will lift up the sons and daughters of the Jews in exile. These Gentiles can be seen as the Persians, who provided support for some Jews to return to Jerusalem from Babylon.

In the next verses we read, “Kings shall be thy nursing fathers, and their queens thy nursing mothers: they shall bow down to thee with their face toward the earth, and lick up the dust of thy feet; and thou shalt know that I am the Lord: for they shall not be ashamed that wait for me. Shall the prey be taken from the mighty, or the lawful captive delivered? But thus saith the Lord, Even the captives of the mighty shall be taken away, and the prey of the terrible shall be delivered” (Isaiah 49:23–25).

Usually one does not steal prey “from the mighty” (verse 24)—you don’t take a gazelle from the lion that is munching on it. But if we keep in mind the context from the Isaiah Map, we can continue our interpretation from the previous verse. We could see the prey as the Southern Kingdom and the mighty as Babylon. Shall the prey (Judah) be taken from the mighty (Babylon)? Yes! Although it seems impossible, Persia, represented as nursing fathers and mothers, will deliver captive Judah from the hands of Babylon.

Having analyzed these verses using the context provided in the Isaiah Map, we can now do a better job of likening this passage to our lives. The Jews felt that they had been forgotten—and perhaps rightfully so. They were experiencing a multigenerational trial! The message that the Lord has not forgotten his covenant people is an impressive call to hope. He did not forget the Jews in exile, and He will not forget us, although His help may not always come in the time frame we desire.

Another way to understand this passage: Just as the Jews were captive in Babylon, we are held captive by sin and death. And just as God used the Persians to free the Jews, so too the Atonement of Jesus Christ helps us conquer these seemingly invincible foes. Understanding the historical context of these passages adds greater depth to our understanding of the delivering power of the Savior’s Atonement (see 2 Nephi 9:25–26).

I hope the Isaiah Map will help you in your quest to comprehend Isaiah. His words are much easier to understand and apply to our day when we first understand how his teachings relate to the circumstances of his day. Most important, as we better understand Isaiah’s context and history, we can also more clearly see how Isaiah points us to Jesus Christ and His power to save each of us.

If you want to see more specific examples of how this map can be used to understand specific passages of scripture, you can read my article that covers more information on the subject. Or watch the video below—it’s part of my free course called “Seeking Jesus,” which focuses on helping you learn all you can about Christ from the scriptures and other sources, such as modern prophets, music, artwork, movies, and modern scholarship.

⟶ Download a copy of the Isaiah Map here.

▶ You may also like: 5 tips from John Bytheway to understand and love the Isaiah chapters