As Christmas carols are playing full-force, there is one found in the Latter-day Saint hymnbook that has an especially tender story behind it.

"I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day" was not a hymn to start with. Rather, the song is based on a poem by the well-known American poet, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

On July 9, 1861, Longfellow's wife was sealing packages with clippings of her little girls' hair with wax when her dress caught fire from a match on the floor, according to Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: With Extracts from His Journals and Correspondence.

Rushing away from her children, she ran into Longfellow's study, where he tried desperately to beat out the flames.

The next day, Longfellow's wife died from her burns and Longfellow himself was too badly burned on his face, arms, and hands to attend the funeral.

From that point on, Longfellow's journal entries around Christmas time turned steadily bleak.

His entry on December 25, 1861, reads, "How inexpressibly sad are all holidays! But the dear little girls had their Christmas-tree last night; and an unseen presence blessed the scene" (Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow).

The next Christmas, he wrote, "'A merry Christmas,' say the children; but that is no more, for me. Last night the little girls had a pretty Christmas-tree" (Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow).

Then on December 1, 1863, Longfellow received a telegram that his son Charles, a lieutenant in the Army of the Potomac, had been injured.

Longfellow rushed to Washington and waited three agonizing days before Charles arrived with other wounded soldiers. The army surgeon told Longfellow his son's wound—a bullet that passed under Charles' shoulder blades severely injured his spine—was very serious and might result in paralysis.

That Christmas, Longfellow did not write in his journal at all.

But the following Christmas of 1864 was different. That year, Longfellow wrote a poem that would later inspire one of the most well-known Christmas carols—that poem was "Christmas Bells"

I HEARD the bells on Christmas Day Their old, familiar carols play, And wild and sweet The words repeat Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And thought how, as the day had come, The belfries of all Christendom Had rolled along The unbroken song Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Till ringing, singing on its way, The world revolved from night to day, A voice, a chime, A chant sublime Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Then from each black, accursed mouth The cannon thundered in the South, And with the sound The carols drowned Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

It was as if an earthquake rent The hearth-stones of a continent, And made forlorn The households born Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And in despair I bowed my head; "There is no peace on earth," I said; "For hate is strong, And mocks the song Of peace on earth, good-will to men!"

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep: "God is not dead, nor doth He sleep; The Wrong shall fail, The Right prevail, With peace on earth, good-will to men" (Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth. "The Complete Poetical Works of Longfellow." Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1893.).

Though it's not clear what caused Longfellow to change his attitude toward the holiday and express his faith, the words are as inspiring as they are hopeful.

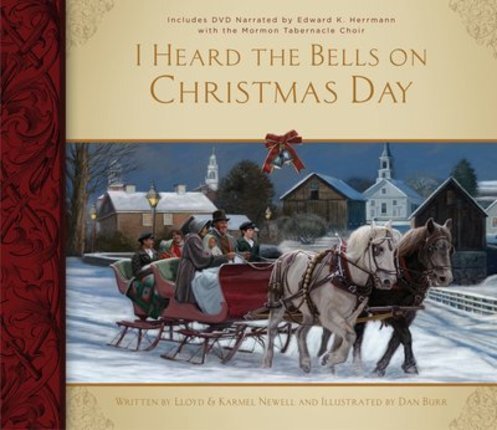

Parts of "Christmas Bells" were arranged by John Baptiste Calkin in 1872 and became "I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day," a beloved Christmas carol. Later, the song became included in the Latter-day Saint hymnbook and showed the power of hope amid great tragedy.

Reeling from the tragic death of his wife and the war wounds of his son, Longfellow penned the words to “Christmas Bells” during one of the darkest times in American history. And while the words of the poem reflect his obvious despair and grief, it is the triumphant message of “peace on earth, good will to men” for which this song—and Longfellow's personal story—is remembered.