The first time I saw the LDS missionaries was through the scope of my sniper rifle—their white shirts strikingly visible against the intense green of the jungle. Who would dare be so visible in the middle of a war?

During my seven years in the Cuban military, I was trained by the Soviets and Vietnamese to carry out special warfare and insurgency operations throughout the world. We smuggled guns, ammunition, people, and explosives to 27 countries. We exploited revolution in Africa, Asia, and Central and South America. We made war—that was our only purpose. Though I had no faith of my own, my grandma had taught me the principles of the Bible well. Throughout my missions, her words were always in the back of my mind. I would need them to become the man I wanted to become. And, as I would find during a mission deep in the Guatemalan jungle, I would need them to stay alive.

I joined the Cuban military right out of high school and stayed there for seven years. The military in Cuba is compulsory, and you can opt to be drafted as soon as you finish high school or after you finish college. But my mom had a very difficult time after she got divorced, and the domestic environment was not easy for me. So after high school, I just wanted to go away; the military provided mobility.

Though the domestic situation with my mother was never very good, my childhood had been happily spent in the company of my great-grandmother. Because my mom worked in a research facility pretty far away, my grandma was my main emotional attachment for many years. She was, more or less, my most significant relationship.

Growing Up with Grandma

My grandmother had a deep faith. She constantly taught me about the Bible, especially the words of Isaiah and his prophecy of a temple in modern times. This temple, and whatever took place in it, was critical to Grandma's view of God.

One night, she told me, "God is the same yesterday, today, and tomorrow. He has been my God since I was 23 years old and will be my God forever. God gave men clear instruction of how He wanted His church and His affairs handled. Men, in their arrogance, changed everything. They broke the commandments; they changed how things ought to be done. Thus, they’re cut off from Him."

"So, God isn't with us any longer, then. Are we on our own?" I asked.

"No, Son, He is here," she said with certainty. "You tell God that you know He is there, that you know you're cut off from Him because we've lost the way, but that you love Him. He will hear you."

Right before I left for the military, she warned me of the dangers and implored me to remain clean. "I send you out into the world in the hands of God. I urge you to seek Him in everything you do. I'll pray for your safe return day and night until you come back. But keep silent prayers in your heart always, listen to His voice, and you'll be safe."

And off I went. They did some tests and I scored high in certain areas; I had also studied martial arts since I was young. Because of these things, they told me I would do well in special forces. I figured if I was going to go with the military, I might as well go with the best and the brightest.

In the Field

I worked for the equivalent of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and they would call me any time of the day or night. What my group did, for the most part, was to shadow enemy troops. The Central American Civil War—the Dirty War, as we called it—was a war of proxies. The U.S. was not directly involved, neither were the Soviets. They used proxies to fight the war for them.

The U.S. had CIA, special forces, trainers, and military advisors on the ground. The Soviets had them, too. The Cubans did the fighting, the training of insurgents, and so forth. Our task was to follow the enemy troops, and occasionally to grab military officers and pass them along for interrogation.

One time, our mission was to extract a lieutenant. We watched him go into a bar and brothel, on the second floor. The idea was to grab him without having to destroy the place, shoot people, or make a lot of noise—and all we had was an ice cream push cart.

We got to the second story of the building with a rope; we came in through the window, shot him with a tranquilizer, and put him in the ice cream truck. But when you lower the temperature, it diminishes the effect of tranquilizers. So we started pushing this ice cream truck down the street, and he started kicking and screaming. People were looking at us, shocked, and asking, "What have you got in there? A pig?" We tried to assure them that it was just a pig, but we had to finish up—fast.

We ran to the end of the street where the extraction truck was waiting. When we opened the lid of the ice cream cart, he jumped out and started running down the street. Now it just so happened that at the end of the street there was a mental hospital, so the people were afraid that he was a patient, and they actually helped us get him. We shot him again with the tranquilizer and got him in the truck.

Months later, we were in a town nearby, and an old man came up to me and said, "Hey, doctor, how are you?" I was confused. Doctor? Then he asked, "How did the situation with your patient end up? Did you get him back in the hospital?"

Then I realized he was talking about the lieutenant. "Oh, yeah!" I said. "He was totally insane." My comrades and I laughed. From then on, my friends started calling me Doc. It was a story we told many times.

In what we did, humor was a way to keep your sanity, because if you started thinking about what you were actually doing, there was no reason for laughter.

White-Shirt Lunatics

You have to understand there are three rules in the jungle. One, you have to blend. If you don't blend, you're going to become somebody's lunch real fast. The other rule is to move slowly. If you're moving too fast, you can't hear anything, such as something coming up on you. The last thing that is really important is that you have to be aware of the environment—you don't make yourself known.

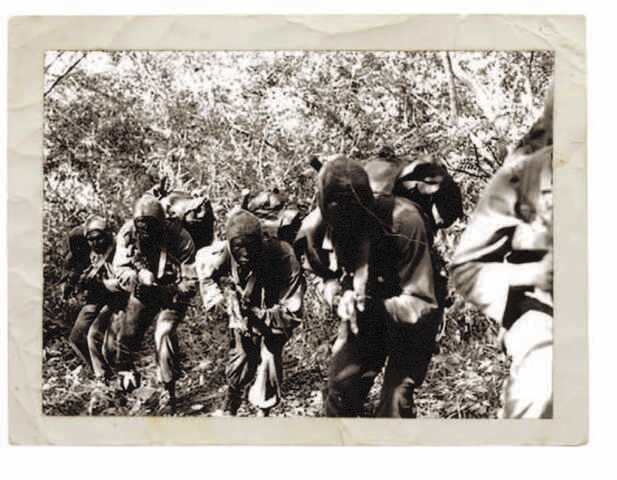

One time we were waiting for an equipment drop on a hillside in the jungle. Suddenly, something came out of the bushes and started coming down the hill—and whatever it was, it was ignoring all three of the jungle rules.

I looked closer and it was two kids—jumping around, happy, talking, and not paying attention to anything. They're lunatics! I thought to myself. They're gonna get themselves killed. They were wearing white shirts and ties in the jungle, skipping and jumping animatedly down the hill. I could see one laughing. "Who are these people?" I said out loud.

"Oh, they're missionaries," said one of my comrades.

To me, my grandmother's student, this was fascinating, but my companion didn't seem to care. Who in their right mind would come into this godforsaken place, in the middle of a civil war, to talk about God? The missionaries had safely gone about their business, but the memory of those white-shirted boys lingered for days.

The Darkest Night

I had missions in which we were able to go out and execute and come home, and everyone was safe. That was reason to be glad. And I had missions in which I lost many of my friends. On my last mission, most of my comrades died.

Photo courtesy of Malcolm Leal

The mission started benignly enough. "Perestroika" was in effect, which meant that goods, spare parts, and supplies decreased. So a mission was put together to bring in Soviet specialists and needed supplies. My unit was tasked with accompanying two Soviet "technicians" on a two-week maintenance expedition. Not a glamorous assignment, but still one of high priority since our side was becoming blind and deaf to the movement of the enemy on the Nicaraguan border.

In two days we were done, which was record time for the mission. At the appointed time, the communication specialist signaled that he had a link.

"Control, this is Vector, we're looking good and en route to the rest point," I said.

"Excellent. We have one more recovery point, Sergeant," said the man on the other end.

When you gear up for a mission, you prepare for the unforeseeable. If you change the mission, someone is going to die, because you cannot anticipate all the variables. Changing the mission was this man's mode of operation, and countless men had paid for his games with their lives. And now he was doing it to us.

I listened motionlessly as the instructions came. After the transmission ended, I briefly discussed the details of the "detour" with one of the mission's specialists. The change of plans included moving back north-by-northeast, across enemy territory.

After three days of a painful and treacherous march in the jungle, we reached the recovery point. An accident involving one of my men meant that I had to continue on my own to retrieve the equipment while the other soldiers waited in a secure location.

I reached a hidden spot not far from the gear, which was set on a rock outcrop 20 yards away. To retrieve it, I had to completely expose myself, and I'd be facing away from the tree line across the gorge. I clasped my weapon and broke into a soft jog to the massive rock formation. My fingers made contact with the slippery, cold surface of the camera. I pulled.

The next moment, it felt like a sledgehammer hit me sideways on the head. A flash of lights, bright and blinding, filled my eyes, accompanied by a high-pitched hissing sound. Then nothing. Nothing at all, as if I'd been suddenly pushed into space—total sensory shutdown. A few seconds later, maybe minutes, the pounding of my pulse on my temples and the coppery taste of blood in my mouth attested to the absolute fact that I had been shot in the head, and my life had come to an end. I lay there broken, unable to move for what seemed like a lifetime. I sobbed quietly, helplessly.

I was dying. I thought of my grandmother. What could I say to her God? It occurred to me then that I'd wasted my life. I spat the blood and mud from my mouth and twisted my body painfully, slowly to face heaven. I cried some more.

"God of my grandmother, I know about You, and I believe in You. I'm about to die, and maybe I deserve to die; only You know that. Take me then, God, and don't let me suffer any longer. Comfort my grandmother, for she is old and she loves me. I pray that You may forgive me of all my sins. Forgive me, God. Forgive me." I wept again; now, however, I felt almost happy. I slipped into unconsciousness.

"Not yet," I heard inside my rattled brain with astonishing clarity.

The quiet and simple phrase startled me. I was in shock due to the loss of blood. The magnitude of the event, the realization that I had been a witness and a recipient of a true miracle and how this event would transform my life would come days later.

Miraculously, I got up and walked for six hours, finally making it to a place where I could wire for help and be picked up. When the medic jumped out of the chopper, he approached me and his eyes looked like they were ready to pop out of their sockets. "Don't worry," I said. "It looks worse than it actually is."

I woke up a week later at a hospital back on the island, a symphony of monitors, bells, and whistles serenading me in the hospital room. Nothing could have prepared me for the shock of the first glance at myself after the injury. My head, what was visible, was obviously swollen and misshapen. I had a scar from ear to ear and stitches like a baseball. My romantic life is over, I thought.

Eventually, as with every other mission, I was able to go home. Going back home meant that I had to talk to my grandmother about what happened. When we discussed what she thought about it, what it meant in my life, she said, "God's is the forgiveness, mercy, and peace that you felt, and that's the foundation of faith. Don't let it die, don't forget that day. One day you'll find the church that will fill your heart."

Time to Defect

It was a known fact that politics killed people. In my case in particular, lots of people got hurt. I thought the change in the mission was unnecessary—someone was playing politics on the fly. For me, as a soldier, as a leader of a unit, that was not acceptable. And I made some threats.

As a result, my commanding officer, Montes, a man I had grown to love and respect as a father, arranged to send me away. He told me, "There will be an 11-month tour and a scheduled rotation back to the home base. Come back with the last group. On the layover in the third country, get off the plane and don't look back." The commanders feared me, and when they fear you, they kill you. I knew I wasn't coming back.

I tried to conceal from my grandmother my inner struggles in regards to the future. But she understood. I stayed home that summer as much as I could. I wanted to remember; I wanted to hold on to her and a life of experiences near her so that she was never forgotten.

I eventually left for Europe, spending most of my "time away" in East Germany training young operatives. Then, during the winter I was there, the Wall came down. Without almost any warning, Communism evaporated in one winter night.

These were dangerous times. The secret services were on the prowl during rotation times at our office. These were the times when people jumped fences, drove across bridges, and walked into embassies different from their own. My opportunity came on the journey back to the island.

We stopped in Montreal. Secret police—prison keepers, for we were all prisoners of the state—came with us to make sure no one escaped to a receptive country, so I had to arrange a convincing excuse to step away from them. After taking quinine before landing, I needed a bathroom, and everyone could see it. Once inside the stall, I climbed over the toilet, onto the divider wall, and removed the false sheetrock ceiling plank. I pulled myself behind the bathroom fixtures, replaced the sheetrock plank, and let darkness engulf me.

As I crawled through the dusty and damp space, I hesitated when a flash of light surrounded me. It had to be them. I pushed down on the ceiling plank underneath me, fell into a small room, and ran. I heard shouting and what seemed to be a rush of people running and cars braking. I ran faster than I had ever run and longer than I thought possible.

The last 30 miles to the United States border remained a blur. As I neared the border patrol checkpoint, I went very slowly. I was, after all, dressed in a military uniform of a foreign country.

What happened next belongs in a comic strip. By the time the border patrol officer saw me, I was less than 20 feet from him. He was frantic. He dropped his gun and radio and picked up the radio, pointing it at me. "Freeze! Stop!" he yelled, the antenna of his radio pointing at me, while he clasped his gun and put it to his mouth as if it were the radio unit. "I need help now!"

After the mix-up, a handful of officers rushed to help their fellow agent, handcuffing me and taking me away.

They took me to a Virginia farm to be questioned, to be sure I wasn't a threat. After six weeks there, I was taken to my chosen location: Los Angeles. A chapter of my life had ended and a new one was about to unfold.

Missionaries, Again

I settled in L.A., got some education, and even began a family. But in eight years, I still hadn't found the fulfillment I sought. Periodically I would take up my search for "the church that would fill my heart," but I wasn't impressed by any of them. I needed more.

Around Easter of 1998, I was very sad. Easter was very sad for me because it was sad for my grandma. In Cuba, people did pretty bizarre things on Easter. My grandma thought it was a mockery of Christ's suffering. My brother had also recently written to tell me that Grandma had died.

Around that time, I was watching TV when a commercial came on for a video about the birth, teachings, and crucifixion of Jesus Christ. It was simple, yet powerful. I ordered it, and about a week later, a couple young men dressed in shirts and ties rang my doorbell. I had to get to work, so our visit was brief. But they gave me the video, and a book.

I watched the video about a week later. That Sunday, I picked up the blue book the missionaries had left. I flipped through the pages until I read something that literally took my breath away: "I will read unto you the words of Isaiah" (2 Nephi 6:4). "Isaiah!" I exclaimed, jumping to my feet.

Memory and experience found great resonance with the text. In years of roaming the jungle, I had seen countless pre-Columbian ruins like the book described—fortifications. I read the familiar words of Isaiah, this time in the voice of Jesus Christ. I read throughout the day. I thought about the events leading to that day; I thought about the many years of reading and searching. It seemed like the walls of a dam had broken and a flood had rushed in, inundating every corner of the land inside me. "I've found it," I sobbed. "After all this time, I've found it."

A Happy Life

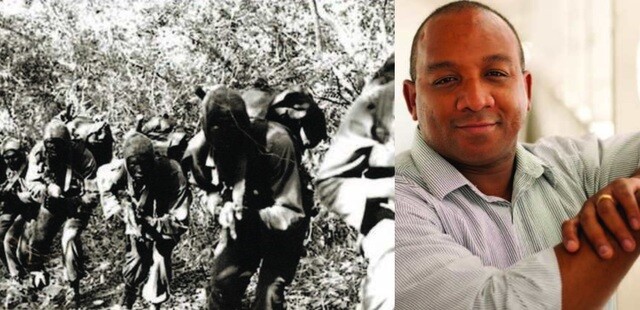

Photo by Brad Slade

It took me three weeks to find the missionaries again, but they finally came back. Night after night they returned. I attended church and made many new friends in a very short time. What I saw and felt in that church building sealed my testimony of the truthfulness of the Book of Mormon. A few days later, I was baptized.

In Cuba there were no happy moments. There were times of euphoria; when we were able to go on an operation and nobody died, that was reason to be content. But I wasn't happy.

However, after I came up out of the water on my baptism day, I couldn't help feeling that I'd found my home. I was more than happy. I'd been lost, cut off, and disconnected for most of my adult life. For once, I was certain I was in the right place.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Adapted from Faith Among Shadows: One Cuban Soldier's Journey to Find the Gospel of Christ.

This story originally ran on LDS Living in 2009.