Few things bring the spirit of Christmas into our lives more than music. To help invite that spirit, here’s a brief history of two Christmas hymns—“Joy to the World” and “Silent Night”—that can bring added meaning to your Christmas celebrations this season.

“Joy to the World”

Text: Isaac Watts (1674–1748);

altered by William W. Phelps (1792–1872; LDS)

Music: George F. Handel (1685–1759);

arranged by Lowell Mason (1792–1872)

Tune name: ANTIOCH

Ever since Emma Smith included it in her hymnal of 1835, this energetic and dignified hymn has been a favorite among Latter-day Saints. Today we follow the practice of the rest of the Christian world in using it mainly as a Christmas carol.

But this hymn has also served a second purpose: it is clear that William W. Phelps’s intention was to adapt it as a millennial hymn. The early Saints loved to sing of the millennium, and with some changes in verb tense—such as “The Lord will come” (rather than is come)—and a few other alterations, William W. Phelps made it suitable for that purpose. It is interesting that Isaac Watts’s original title for the hymn suggests this millennial spirit: “The Messiah’s Coming and Kingdom.”

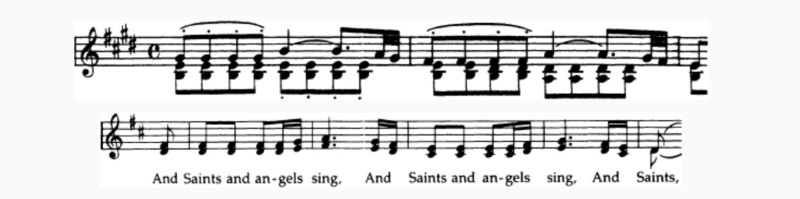

The 1985 hymnal returned to the traditional verb tense in the opening line—”the Lord is come”—preserving the more common Christmas message. Other changes made by William W. Phelps have been retained, however, such as the line popular among members of the Church: “And Saints and angels sing” (rather than “heaven and nature”).

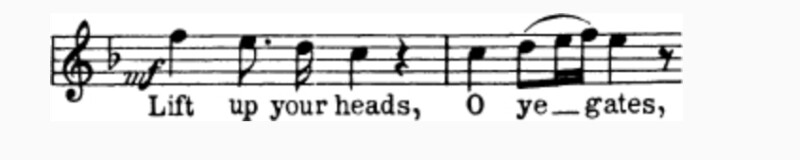

George F. Handel and Lowell Mason share credit for the remarkable melody. (Note how the first phrase is nothing more than a descending major scale!) How Lowell Mason arrived at the tune is not perfectly clear, but it is possible that he brought together two melodic suggestions from Handel’s Messiah. First was the opening of “Lift Up Your Heads”:

This phrase suggested the first measures of “Joy to the World.” And the first measures of the accompaniment to the tenor aria “Comfort Ye My People” became a later passage in “Joy to the World”:

Lowell Mason himself gave principal credit to George F. Handel; when he published “Joy to the World” in Occasional Psalms (1836), he marked it “Arr. from Handel.” We do not know for sure why he named the tune ANTIOCH; he took Bible names almost at random for his tunes.

“Silent Night”

Text: Joseph Mohr (1792–1848);

translated by John F. Young (1820–1885)

Music: Franz Gruber (1787–1863)

Tune name: STILLE NACHT

The holy child and his mother, the shepherds, the angelic hosts— the scenes from the scriptural account of the Nativity are referred to only in the briefest way in this beloved Christmas hymn. Yet the peaceful, familiar melody evokes the entire scene. As we sing, our hearts and memories fill in what is missing, and our sense of that sacred night is complete.

It is amazing to realize that this best-known of all Christmas carols was virtually an “instant hymn.” The words were written, set to music, and first performed all in a single day. Though fanciful stories often spring up over the years about popular hymns, the account that is often told of the writing of “Silent Night” can in fact be documented as historical. This carol was written in an attempt to make the best of a musical emergency when the organ of a small Austrian church broke down on the morning of Christmas Eve.

On December 24, 1818, Father Joseph Mohr, the assistant parish priest at the St. Nikolaus Catholic Church in Oberndorf, Austria, decided to write a new hymn for the evening service. Because the church organ could not be repaired in time, he needed a Christmas hymn that the organist, Franz Gruber, could accompany on his guitar. He took the words to Franz Gruber, who wrote the music, and the two of them sang the hymn at the evening service, with the choir joining in on the last two lines.

The carol’s fame spread far faster than that of its creators. Traveling musicians soon popularized it throughout Europe and the United States, and the tune was attributed to many different composers, including Mozart! But in 1854, Franz Gruber wrote a public letter setting the record straight and establishing proper credit for himself and Father Joseph Mohr. The original hymn text was quite a bit longer; today English- speaking congregations use the first, sixth, and second verses of the original. The translator was John Freeman Young (1820–1885), an American Episcopal bishop. The tune, also, has been changed somewhat from Franz Gruber’s original melody.

The tune name, STILLE NACHT, is from the first two words of the original German hymn, meaning “quiet night.”

Our Latter-day Hymns: The Stories and the Messages

Prepared with the cooperation and assistance of the General Music Committee of the Church, this companion to the hymnbook gives brief biographies of the authors and composers of the hymns, the stories of the hymns themselves, and an account of changes that may have occurred in the words or in the music.