On a Tuesday morning before the world outside turned upside down, it was quiet and peaceful in the Washington D.C. Temple.

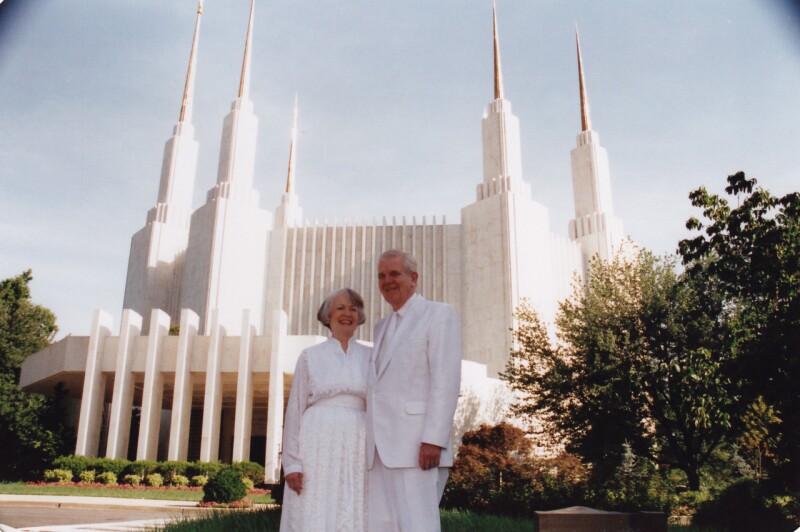

The temple presidency’s first counselor, Ed Scholz, and his wife, Lois, were on duty that day. They arrived at 5:00 a.m. for their 12-hour workday. At 6:30 a.m. they met with the first shift of workers for a prayer meeting. Then patrons began arriving for sessions, and the spirit in the temple picked up as the work of salvation for the living and the dead began anew. As usual, no television or radios were in the temple, even in the presidency’s offices, because they would disturb the sacred space.

At 8:46 a.m. that day, September 11, 2001, a passenger jet slammed into the 110-story north tower of the World Trade Center in New York City.

As he sat in his temple office going over reports, Scholz received a call from one of his daughters. “Dad, a plane just flew into the World Trade Center,” she said. Scholz shared the news with assistant recorder John Laing. “We both mused that it was probably a Piper Cub that just got blown off course or lost its maneuvering somehow,” Laing said. Scholz recalled that a B-25 bomber had accidentally struck the Empire State Building in a fog decades earlier.

At 9:03 a.m., another passenger jet slammed into the WTC South Tower, and Scholz’s daughter called again. At that news, Scholz and Laing became very concerned about what was most likely a major terrorist attack in New York City, but they did not see it affecting the temple in the nation’s capital.

Meanwhile, after finishing a round of tennis at home with friends, temple president Sterling Colton turned on the TV to see news reports of the two smoking buildings in New York. “It was terrible, unbelievable,” he wrote in his journal. Having been the Marriott Corporation’s long-time general counsel, Colton was alarmed about the fate of the guests and employees in the 22-story Marriott World Trade Center, a smaller building nestled between the two towers. But because he viewed it as a New York City event, Colton did not feel the necessity of going to the D.C. Temple. Also, he knew that if anything needed to be done, his counselor Ed Scholz could handle it. He was right about that. In fact, many experiences in Scholz’s life had prepared him to react calmly and effectively in the face of a threat.

The grandson of a Baptist minister, Ed was born in Berlin and was on the receiving end of Allied bombings during World War II. But in truth he was more afraid of his government than Allied bombers: His father refused to join the Nazi party and was put to death by Adolph Hitler’s government in 1942, and his only sibling, his older brother, Siegfried, was killed after being drafted into the German Army.

When the bombing of Berlin became more intense and food shortages were prevalent, 10-year-old Ed and his mother fled 25 miles from Berlin to the farming village of Storkow. In the village, Ed had many harrowing wartime experiences, which increased in danger toward the war’s end when undisciplined and often uneducated Russian troops occupied the village. In one instance, Russian privates put the town’s baker against a wall preparing to execute him as a “capitalist” because he owned a piano. The baker was the father of his best friend so, without fear, Ed rushed with five boys to stand in protest between the baker and the rifles, ultimately saving his life.

Scholz later immigrated to the United States and joined the U.S. Air Force, in part to gain American citizenship. He met and married a former fellow Baptist, but now Latter-day Saint convert, Lois Groves. She was just as implacable and fearless as her husband.

During the October 1962 missile crisis, when most Americans felt sure a nuclear war was about to erupt, Ed and Lois were on the front line. He was stationed at the Loring Strategic Air Command base in Maine when he and his crew were called up on the highest alert to prepare for a nuclear bombing flight. When the couple said goodbye, they were both calm. They did not know if they would see each other again in this lifetime, so they held hands in the same way they had on a temple altar when they were sealed—reminding each other that this was but a small moment in time and their marriage was for eternity.

So, when at 9:37 a.m., on September 11, 2001, a third plane hit the Pentagon just 22 miles southeast of the temple, Ed and Lois did not hesitate to journey to the roof of the Washington D.C. Temple for a better look and to search the skies for other possible threats.

The couple took the elevator to the seventh floor and then climbed a hidden stairwell to the eighth floor and into the elevator operation housing. From there, they scaled a 20-foot vertical steel ladder bolted to the wall. It was not an easy feat for Ed and Lois, who were 68 and 65 years old respectively. John Laing, the assistant recorder, joined them, and even though he was much younger, it was arduous for him as well.

“It is a very steep ladder that led to a big, heavy door—super heavy because it has marble and steel on the outside of it,” explained then-engineer Luis Alvarez. “It’s the only access to the tar roof, then covered with a layer of beige stones.” There was no railing at the top to prevent a precipitous fall, so the trio wisely stayed away from the edge.

Recalling the unusual journey so many years later, Lois said: “We were all dressed in white temple clothes, and I wondered if anyone saw us. The wind was blowing up there, and it would have been startling to see three people dressed in white on top of the temple.”

As the trio gravitated to the south side of the roof facing the Pentagon, they looked upon the scene in horror.

“Ed was sick to his stomach to see that large plume of smoke ascending upward from the Pentagon. As an Air Force colonel, that was where he had worked before he retired from the military, so it was kind of like home to him and was particularly hard for him to take,” Laing explained. “He still had friends in that part of the building.”

Ed was also “very concerned about the flight path of more airplanes and worried about one hitting the temple spires,” Lois noted.

▶ You may also like: ‘One step at a time’: What 1 woman’s escape from the 99th floor of the South Tower on 9/11 can teach the next generation

Laing was absorbed with a similar thought—that “this enemy, whoever it was, seemed to be hitting prominent buildings, and the Washington D.C. Temple was a sitting duck target.”

In fact, at about the same time, passengers were attempting to retake control of United Airlines Flight 93 from terrorists, who then crashed the plane near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, about 130 miles northwest of Washington. Most intelligence analysts have concluded that the terrorists’ target for that plane was the White House, which would have put it on a flight path near or even directly over the temple.

After the Scholzes and Laing descended from the rooftop, a temple guard with binoculars went up to the roof to search for any threat from the sky, which fortunately never came. In its long history, the temple rarely closed—even during large snowstorms, power outages, and other events—and this day was no exception. The Scholzes fielded phone calls throughout the day, reassuring patrons that the temple was still open.

Meanwhile, a distraught President Colton came to the temple in the late afternoon. Having kept in close touch with his close friend and former boss, Bill Marriott, Colton learned that when the towers fell, the hotel was crushed out of existence. While heroic Marriott hotel managers were able to get most of the guests to safety, two died while making sure every room had been checked. Ultimately, 11 of the 940 registered guests in the hotel that day were unaccounted for, but most likely they were in the main towers attending business meetings or shopping.

In his journal President Colton recorded that a call came at 5:00 p.m. from President Gordon B. Hinckley, directing that the D.C. Temple be closed. “President Hinckley said the closure was not because he thought the temple was in danger, but because it was a way to honor those who had already died or were otherwise affected by this terrible event,” Lois said. Colton added in his journal: “We decided to complete the endowment for a young missionary and didn’t close the temple until about 7 p.m.” The doors of the temple were then shut, having received no serious threat that day.

From the Tabernacle at Temple Square, President Hinckley offered a public statement of sorrow and consolation: “Dark as is this hour, there is shining through the heavy overcast of fear and anger the solemn and wonderful image of the Son of God, the Savior of the World, the Prince of Peace, the exemplar of universal love, and it is to Him that we look in these circumstances. It was He who gave his life that all might enjoy eternal life. … May the peace of Christ rest upon us and give us comfort and reassurance and, particularly, we plead that He will comfort the hearts of all who mourn.”

▶ You may also like: The mistakes and miracles behind the massive new Second Coming painting in the DC Temple

Following President Hinckley’s counsel to help offer “comfort and reassurance,” Ed Scholz began a new duty after that day: he began counseling with at least three new widows among the temple workers, whose husbands had died in the Pentagon attack. The temple reopened the next day, according to Lois, “and the Lord’s business continued with a renewed sense of union and purpose among the patrons.”

This article was adapted from Dale Van Atta’s book, The Washington D.C. Temple: Divine by Design, available at dalevanatta.com and at Deseret Book.