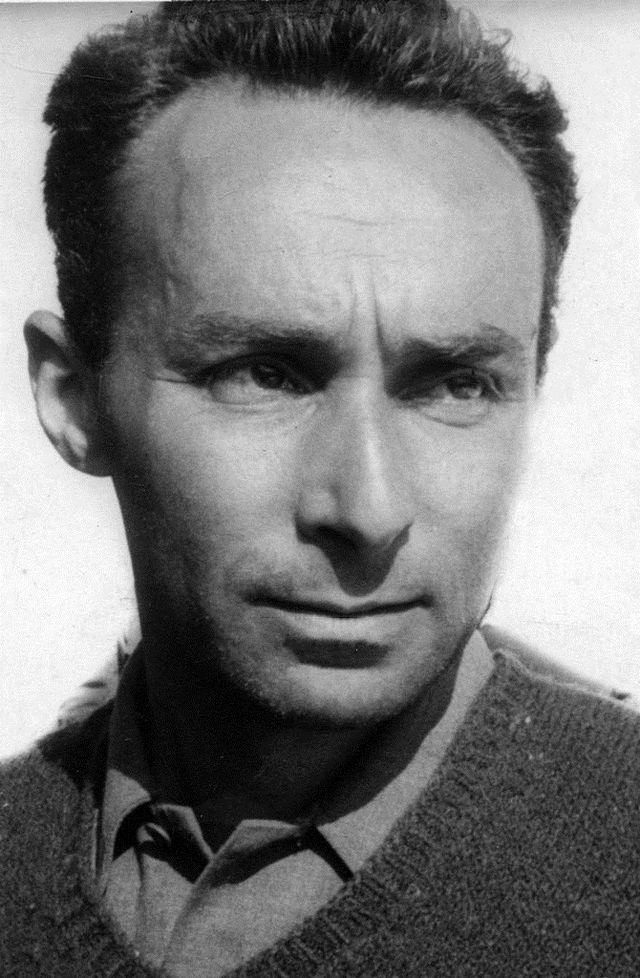

In Auschwitz, a thirsty prisoner reached out the window of his bleak hut for an icicle. A guard, spotting the action, knocked it from his hand before he could find even that scant relief. “Why?” asked Primo Levi. “Here there is no why,” replied the brutal guard. Having both seen and experienced the worst that one human can do to another, Levi later wrote, “If there is an Auschwitz, then there cannot be a God.” Decades later, he added in pencil, “I find no solution to the riddle. I see, but I do not find it.” Then, devoid of a solution to life’s most terrible question, he took his own life.1

In the face of unimaginable human suffering, and in the presence of unspeakable evil in the world, it is important to say this at the outset: even the gospel does not have an answer to every question, an explanation for every experience through which we pass. Religious faith and intellectual aspiration alike operate best in a climate of humility, where amid the search for understanding we recognize the limitations of our vision. However, the Restoration does provide a satisfactory theological framework in which we can begin to make sense of the coexistence of a benevolent God and the moral atrocities and natural calamities that surround us. In part, this is because Restoration conceptions of God avoid the insuperable problems that are implicit in conventional doctrines of the Divine and that have been pointed out for centuries.

The classic problem of evil is simply expressed: evil exists; either God is unable to prevent it (in which case He is not omnipotent, perfectly powerful), or He is unwilling to prevent it (in which case He is not omnibenevolent, perfectly good). Given this stark choice, most influential thinkers in the Christian tradition opted to preserve omnipotence, at the cost of what most would understand as perfect goodness. Hence, in this view of absolute sovereignty, God “at his own pleasure arranged the fall of the first man and in him the ruin of his posterity,”2 for “nothing takes place but as [God] wills it.”3

Even assuming that God chooses to respect our freedom to hurt and abuse and kill one another, if He is the Creator of all that exists, including our souls, why did He not endow us with more beautiful, kindly souls? A twentieth-century philosopher pointed out this most obvious, fatal flaw in the orthodox view of God: If He created our souls, He “could have prevented all sin by creating us with better natures and in more favorable surroundings.”4 He chose not to. We find ourselves to be inclined by nature toward selfishness and sin. So in this view He is God the omnipotent, the all-powerful Creator. But He is not omnibenevolent because He did not create our souls in a way that predispositioned us all for salvation.

Our attitude to evil must be twofold: we must be tolerant of it as the Creator is tolerant, and we must mercilessly struggle against it.

Restoration thought embraces the other horn of the dilemma. Joseph Smith restored a God of infinite goodness and kindness but not infinite creative power, with words unique in the Christian tradition. “God himself is a self-existent god. … Who told you that man did not exist in like manner upon the same principle? … Intelligence is eternal and exists upon a self-existent principle. It is a spirit from age to age and there is no creation about it. … [We are] self-existent with God.”5 So the core of our being, spirit, or “intelligence,” is not something that God made. The scope of our innate potential for good and evil is tied, in essential ways, to our nature; and that nature is constituted, at its most fundamental level, by an identity that God did not create or impose on us. When that nature, shaped but not determined by contingent factors like environment and genetics, is freed to act out its own inclinations and desires, the consequences range from the goodness of Anne Frank to the evils of Auschwitz. The freedom to enact the good requires the freedom to perpetrate evil. Meaningful freedom cannot exist without the freedom to act in both ways. This is why, as C. S. Lewis put it with economical and irrefutable logic, “either something or nothing must depend on individual choices. And if something, who could set bounds to it?”6 Our capacity to inflict hurt and suffering upon each other is virtually unlimited and is not attributable to God. “Hence,” writes Nicolai Berdyaev, “our attitude to evil must be twofold: we must be tolerant of it as the Creator is tolerant, and we must mercilessly struggle against it. There is no escaping from this paradox, as it is rooted in freedom and the very fact of a distinction between good and evil.”7

This conclusion leaves us with the other half of the good-and-evil problem unresolved—suffering that is not the fruit of moral agency. The child of a colleague of mine suffered from an ALS-type syndrome. His father and his mother bore the incomprehensible pain of watching their little beloved son, step by horrific step, atrophy piecemeal. He slowly lost all physical and then mental functioning, until death released him. Tsunamis, cancers, and death by a thousand other natural causes are not (generally) the consequence of willful human choices. No personal agency is being safeguarded in these cases. Could a compassionate God have not protected us against those forms of suffering that are outside of human control? Can we in good conscience maintain that watching a pure little child waste away from a horrific disease is necessary for our spiritual growth? It is here, once again, where humility must intrude and demand that we not try to resolve the problem with facile comforts. The suffering of another is sacred terrain; we risk desecrating it when we presume to neatly salve their spiritual anguish with our frail verbal medicines.

The suffering of another is sacred terrain; we risk desecrating it when we presume to neatly salve their spiritual anguish with our frail verbal medicines.

A Latter-day Saint can, however, suggest that, as a general rule, it is with our souls as it is with those laws that govern our physical world. “The elements are eternal,” Restoration scripture holds (Doctrine and Covenants 93:33). And God is He who most perfectly understands and operates in harmony with the laws that govern those eternal elements. For a Latter-day Saint, whether in the realm of moral law or physical law, they are eternal and immutable. As Parley P. Pratt explained, “These are principles of eternal truth, they are laws which cannot be broken, … whether the reckoning be calculated by the Almighty, or by man.”8 One ancient prophet even intimates that God’s position as God actually depends on His respect for and observance of these eternal laws (else God “would cease to be God” [Alma 42:13]). To enter into the world of natural law is to be subject to the tragic nature of that world: its bleak indifference to human valuations, its blindness to human suffering.

But God is not indifferent, and unless we are clockwork deists who deny God the power to intervene in human affairs, then we believe God can and does intercede at times to rescue, to save, to succor. In that case, how do we account for the unevenness of God’s response to human suffering? Why indifference at my doorstep and a miracle next door? We cannot know. The calculus is too complex when one tries to factor in the varying efficacy of faith-laden prayers, the infinitely branching consequences of a divine interposition, the sanctifying potential of human pain, and our resilient tendency to revert to a baseline of temperament in the aftermath of miraculous manifestations and catastrophic disappointments alike.

From another angle, we can see how our limited perspective may misread the problem of human exposure to evil. We cannot know what sufferings we have been spared, what interventions, personal and global have transpired in our lives or in history. At the same time, there seems also to be a Boyle’s law of suffering at work in the human psyche. A gas will expand to fill any space that is available to it. So does the elimination of one pain (recovery from a serious illness, for example) create a space, which is immediately filled by our absorption in the next pain that rushes in to fill the vacuum (the chronic pain remaining). A moment’s reflection will suggest that on a scale of infinite possibilities for pain, no matter how much suffering we have been spared, no matter what bounds the laws of God or of nature and human biology have set, the question would remain the same: cannot God alleviate this suffering? Only in a world of imperturbable sameness, uniformity, and emotional insulation from all disequilibrium would this question never arise.

Some skeptics—Christian and nonbelievers alike—dismiss any theology of a limited God, incapable of finding a less-anguishing synthesis of growth, freedom, and suffering. They may find such divine limitations either blasphemous or unworthy of regard. Such a God, however, can be infinitely compassionate, have our best interests at heart, and still preside over a realm of pain and suffering, with no contradiction. Such a God would exist as the most intelligent, loving, and powerful being in the universe—without being the source of that universe. To envision such a God, like the weeping God of the Restoration, is to recognize in God a figure who clearly cannot eliminate our tears, subject as He—and we—are to the constraints of the agency of others, the laws of nature, and the necessity of an educative mortality than can reshape us more in His likeness. To the objection that this view of deity risks the possibility of a fallible God who is incapable of fulfilling His promises, David L. Paulsen, one of our tradition’s premier philosophers, responds that he trusts God “because He’s told us that we can. My faith in God is grounded in His self-disclosures, not in logical inferences from philosophically constructed premises.”9

My faith in God is grounded in His self-disclosures, not in logical inferences from philosophically constructed premises.

Such a God, it seems to me, is infinitely preferable, more worthy of worship and adoration, and more appealing to our instincts for goodness and reasonableness than the God who, in the language of the Christian creeds, is all-powerful, “the source of all that is,” and who ordains all that transpires in history and in every individual’s life. Ironically, we find ourselves in harmony with atheist Richard Dawkins, who finds a Judeo-Christian God operating outside all bounds of logical or scientific law absurd, because “any creative intelligence of sufficient complexity to design anything comes into existence only at the end product of an extended process of gradual evolution.”10 Elaborating this point, he said that “you have to have a gradual slow incremental process [to explain an eye or a brain] and by the very same token, God would have to have the same kind of explanation. . . . God indeed can’t have just happened. If there are gods in the universe, they must be the end product of slow incremental processes. If there are beings in the universe that we would treat as gods, … that we would worship … as gods, then they must have come about by an incremental process, gradually.”11

Latter-day Saints believe in a deity who worked in harmony with invariant laws to shape and organize matter. God is an intelligent being, more intelligent than all coexisting intelligences, who went from glory to glory, from “one degree to another from grace to grace, … from exaltation to exaltation.”12 The Apostle John Widtsoe elaborated: “By the persistent efforts of will, His recognition of universal laws became greater until he attained at last a conquest over the universe, which to our finite understanding seems absolutely complete. We may be certain that, through self-effort, the inherent and innate powers of God have been developed to a God-like degree. Thus He has become God.”13 An official Church position affirmed that fact in 1909, declaring God “an exalted man, perfected, enthroned, and supreme.”14

Two deficits in the Christian tradition … doomed women to an inferior status: the subordinate role of Eve and a God entirely and solely male. Restoration teachings, with remarkable prescience and inspired equity, redressed both impoverished teachings.

At the same time, the Church—with teachings unique in the Christian world—has declared that heaven is not a patriarchal monopoly. In 1895, the feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton pointed to two deficits in the Christian tradition that doomed women to an inferior status: the subordinate role of Eve and a God entirely and solely male.15 Restoration teachings, with remarkable prescience and inspired equity, redressed both impoverished teachings. Restoration scriptures attribute to Eve a crucial role in the plan of human embodiment; she did not doom her posterity but courageously opened the door of mortality to all (Moses 5:11); as for divine parenthood, the leadership has repeatedly affirmed the truth that “all men and women are in the similitude of the universal Father and Mother.”16

Finally, God does inhabit the same universe that we do. He is not a being remote from or existing outside of space and time, transcendent and beyond human categories altogether. He is in space as well as in time. Philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff, writing against the grain of centuries of Christian theology, states the seemingly obvious: “Given that all human actions are temporal,” he reasons, “those actions of God which are ‘response’ are temporal as well.”17 That fact is a core motif of the Restoration. Instead of a single unparalleled eruption of the divine into the human in the unique incarnation of Christ, we find a proliferation of historical iterations, which collectively become the ongoing substance rather than the shadow of God’s past dealings in the universe.

▶ You may also like: Terryl Givens—How can scripture be the inspired word of God if it contains errors?

Let’s Talk about Faith and Intellect

A thoughtful, reflective faith considers the findings of science, the lessons of history, the insights of philosophy, and the best reasonings of our intellect.

Notes

- Os Guinness, Time for Truth: Living Free in a World of Hype and Spin (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2006), 69–72.

- John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, trans. Henry Beveridge (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2008), 630.

- Martin Luther, cited in Michael Massing, Fatal Discord: Erasmus, Luther, and the Fight for the Western Mind (New York: HarperCollins, 2018), 674.

- J. Ellis McTaggart, Some Dogmas of Religion (London: Edward Arnold, 1906), 165.

- Stan Larson, “The King Follett Discourse: A Newly Amalgamated Text,” BYU Studies 18, no. 2 (Winter 1978): 203–4.

- C. S. Lewis, Perelandra (New York: Scribner, 1996), 142.

- Nikolai Berdyaev, The Destiny of Man (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1937), 190.

- Parley P. Pratt, The Millennium, and Other Poems: To Which Is Annexed, A Treatise on the Regeneration and Eternal Duration of Matter (New York: Molineux, 1840), 110.

- David L. Paulsen, cited in Mormonism at the Crossroads of Philosophy and Theology: Essays in Honor of David L. Paulsen, ed. Jacob T. Baker (Salt Lake City: Kofford, 2012), xxxix.

- Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2008), 52.

- “Richard Dawkins Explains ‘The God Delusion,’” Fresh Air with Terry Gross, March 28, 2007, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=9180871.

- Larson, “King Follett Discourse,” 201.

- John A. Widtsoe, A Rational Theology (Salt Lake City: Mutual Improvement Association, 1915), 23–24.

- “The Origin of Man,” Ensign, February 2002, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/ensign/2002/02/the-origin-of-man.

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton, The Woman’s Bible (New York: Prometheus Books, 1999). For a discussion of Stanton and Latter-day Saint theology, see Fiona Givens, “Feminism and Heavenly Mother,” Routledge Handbook of Mormonism and Gender (Abingdon-on-Thames, UK: Routledge, 2020).

- See “Mother in Heaven,” Gospel Topics Essays, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/gospel-topics-essays/mother-in-heaven; emphasis added.

- Nicholas Wolterstorff , “God Is Everlasting,” in God and the Good: Essays in Honor of Henry Stob, ed. Clifton Orlebeke and Lewis Smedes (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1975), 197.