Editor's note: This article was originally published on LDS Living in August 2019.

I recently spoke with a close friend about her suicidal ideations. When I told her we were in the same boat, she balked. And for good reason: no two experiences are the same. Also, those cliché expressions often fall flat. But I meant it in a number of ways.

How often do we have conversations with others, try to empathize, and get scoffed at because there’s surely no way we can understand their pain? As a teen, I had bouts with severe depression, so I knew on some level how this friend was feeling, and reminded her that I was in the same boat, and I meant it. Did I fully understand her exact emotions, her very particular and individual pain? No. Was I there for her—was I proximate? Yes. And that was enough.

One of my favorite short stories is “The Open Boat” by Stephen Crane. He wrote at a time when many felt God didn’t exist, and if He did exist, He didn’t care, and if He did care, there was nothing He could do to help.

It is with that cultural backing that Crane wrote about a newspaper correspondent set adrift on a dinghy with a boat captain, a cook, and an oiler after a shipwreck off the Florida coast. These four men are set against a strong tide, and attempt to row all day and all night for thirty hours, hoping for rescue. They survive a shipwreck, but can they survive the cold night in the floundering lifeboat set against a ceaseless tide?

At one point, the men have reached their worst—they are exhausted, hungry, cold, and far from home. They bicker with one another. They make cutting remarks. They lose hope in the icy, January waters of the Atlantic. The correspondent sets to rowing for the night, taking his turn at the oars. “After a time it seemed that even the captain slept, and the correspondent thought that he was the only man afloat on all the ocean. The wind had a voice as it came over the waves, and it was sadder than death,” Crane wrote.

And while the correspondent is stuck in this darkness, he considers that in those darkest of moments, it might very well be the purpose of God to kill him. Why else would he leave him in that boat alone, set adrift, moving towards certain death?

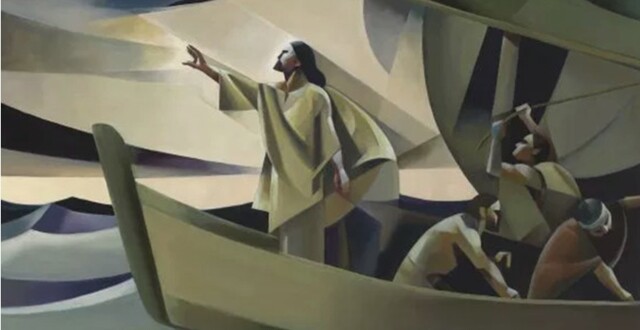

This reminds me of Jesus in Mark 4, when He sleeps on the boat and His disciples lose hope, and panic. Jesus is tired from a long day of teaching, and asks His disciples to take the ship to the other side. There arises a great storm, and the disciples wake Him, fearing for their lives. What is His response? “Why are ye so fearful? How is it that ye have no faith?” (Mark 4:40).

I’d like to stop here and say that when I was in my dinghy and felt alone, faith was not a word that made any sense. It was the last thing on my mind. It wasn’t a matter of faith, but of survival. Minute by minute. Breath by breath. That’s not an exaggeration. When mental illness clouds our view, it is difficult to comprehend anything beyond those thunder bumpers. Faith often seems just another word when depression is skulking in the corners.

And yet, Jesus Christ was in the boat, and He woke up, and the disciples knew it. In my opinion, that was enough. Did He calm the winds and seas and speak peace? Yes. But His presence alone during that storm, I believe, is more important than what came after.

The four men in Crane’s story continue to lose hope. They see a house at one point, a lighthouse, a man waving and yelling about a rescue—and so they rally, but all for naught. Nobody comes. All lightheartedness disappears. The shore feels far away, as it always does. All but the correspondent fall asleep.

As he rows, there is a long, loud swishing at the back of the boat, then a stillness. Then another swish, and a flash of blue light. An enormous fin is seen in the wake. The correspondent looks over to the captain: “His face was hidden, and he seemed to be asleep.” The hulking mass moves through the shadowed water, lurking beyond the tiny dinghy. Above all, the correspondent does not wish to be alone. “He wished one of his companions to awaken by chance and keep him company with it.” But they all slept.

It is in these moments those with depression wonder why they should keep rowing. Why continue? Why push against a tide that cannot be beat? Why row when all others sleep? Why try for the shore? Is the captain in the boat with me? Can I wake him? Is anybody awake? Above all, they do not wish to be alone.

A small moment arrives later in the story. It’s so easy to miss. It seems like a simple section of dialogue moving things along to more important moments in their attempt to make it to shore. But, for me, it is the heart of the story:

“Did you see that shark playing around?”

“Yes, I saw him. He was a big fellow, all right.”

“Wish I had known you were awake.”

That’s it. That’s the moment. Would the shark be any smaller if someone else in the boat was awake with him? No. Would the phosphorescent streak of the massive fin be any less ominous? No. Would chances of survival be any better? Not likely.

Because you may feel that the sharks are circling and they are massive and hungry and your boat is taking on water and the cold swells are more than you can handle. You may feel that everyone is asleep and faith won’t change a thing and the icy waters and dark depths are the only option. But they’re not.

It’s about proximity. It’s about letting those struggling know you are there, that you are present. That is all that matters sometimes. Just being there. You don’t have to have the answers. You don’t have to fully understand their pain—in fact, you often can’t fully comprehend their anguish. And that’s part of being awake: be awake to the fact that no two experiences are the same.

You don’t have to be able to calm the waters and tell them all will be well. You don’t have to speak peace to them or tell them it will all work out. The fact that you are there, that you are close, can sometimes be enough.

I hope you let every friend and person you know dealing with depression know that you are awake. Right now they feel alone, like they are set adrift on cold waters and rowing with no help, their backs sore, their minds tired, their bodies weak, their spirits sinking, and the sun sunk beyond the horizon. You may very well be the captain in their life, and they may think you are asleep. Don’t leave them wishing.

Even if you can’t take an oar, let them know you are there. Let them know you are in the boat with them. Let them know you see the shark, that it’s a big fellow, all right, and that you’re awake for the rest of their journey albeit into that ceaseless tide.