Youth often choose prominent persons as role models, never really expecting to meet them. I chose such a role model when I was in my teens. His name was Dallin H. Oaks.

I turned 15 in 1971, the year he became president of Brigham Young University. Like many active Latter-day Saint youth living outside Utah, I longed to feel a connection with others of my faith who wanted to live the Church’s standards. That made me want to attend BYU, even though my academic record qualified me for attending better-known universities. Attending a summer conference at BYU in 1971 only increased my desire to go to school there.

When I entered BYU in the fall of 1974, I did so with little expectation of ever meeting the president. After all, the university had tens of thousands of students, and I was just one of some seven thousand entering freshmen. As it turned out, I had a brief chance to shake his hand at a reception that fall. It was the only time our paths crossed until after I graduated from law school and was practicing with a large Chicago firm in its Salt Lake office.

On the last Monday in 1985, I returned home from a closing with a client and was walking down the hall toward my office. I passed three women in conversation, one of whom was my secretary. As I walked by, she casually said to me, “Dallin Oaks called.”

I was stunned. I, of course, knew who he was, but I didn’t think he knew I existed. I had tried to model my life after his, going to law school while remaining active in the Church and studying Church history on the side as he had. From his days as BYU president, he went on to become a justice of the Utah Supreme Court, and just the previous year, he had been ordained an Apostle. My admiration for him had only grown over time. But why was he suddenly calling me?

I returned his call; he wasn’t available but soon phoned back.

“Brother Turley?” the conversation began. “Dallin Oaks calling. How are you?”

“Fine,” I replied simply, awed to be talking to my role model.

“How’s your family?”

“Fine.”

“Say,” Elder Oaks asked congenially, “what are you doing for lunch today?”

“Nothing,” I answered, hardly believing I was talking with him.

“Well, why don’t you come over to the Church Office Building cafeteria, and I’ll buy you a bowl of soup.”

At lunchtime, we went through the cafeteria line together, each getting a bowl of split pea soup. As we sat down, surrounded on all sides by Church employees, Elder Oaks pulled out a yellow legal pad and began asking me questions, making careful notes with a number 2.5-lead pencil that I later learned was his preferred writing instrument.

He seemed so friendly, so sincere and unassuming, that it was easy to talk with him. He asked about my family, my background, my education, and my Church responsibilities. Most of all, he asked about my interest in Church history. I told him how I had become intrigued with the topic in my youth, read widely about it, and completed a BYU honors program senior project on an ancestor who traveled with the Twelve to England in 1839. My mentor for the project was the BYU History Department chair, Dr. James B. Allen, who was a former assistant Church historian. Elder Oaks asked me how I kept current on Church history, and I told him about books and scholarly journals I read.

After about 45 minutes, he invited me up to his office, where we chatted for another half hour or so. He told me Church leaders were interested in finding people who were passionate about Church history, but he said little about why. I returned to my law office basking in the glow of having met my role model in person and finding him to be such a kind, engaging person. I wasn’t sure I’d ever hear from him again, but since our firm was busy at year-end, I didn’t have a lot of time to think about it. The New Year’s holiday came midweek, and when I returned to my office on Friday, I was surprised to get another phone call from Elder Oaks.

“Brother Turley?” he began again in the same friendly style. “Dallin Oaks calling. How are you?”

“Fine.”

“How’s your family?

“Fine.”

“I really enjoyed our lunch the other day, and I was talking with Elder Packer about it. Can you come see Elder Packer?”

I said I could. Soon I went to see another Apostle I had viewed only from afar in the past. After 45 minutes of questions, I stood to leave, and as I was walking out the door, Elder Packer said to me in a tone I later came to recognize as his deadpan humor, “If you never hear from us again, don’t worry about it.”

I took the comment at face value and walked back to my law office thinking, “Well, I’ll never know why they called me in to talk,” while at the same time sensing what a privilege it had been for someone in his late twenties to be able to meet one-on-one with two Apostles.

When I got back to my office, the phone rang again. This time it was Elder Dean L. Larsen, the Church Historian and Recorder and Senior President of the Seventy. I visited with him in his office that afternoon and, much to my surprise, he asked me to leave my law practice to direct the Church Historical Department. After conferring with my wife, Shirley, I accepted the role and soon learned that Elder Oaks and Elder Packer were the Quorum of the Twelve advisors to the department, which gave me a chance to work regularly with them.

As Elder Oaks’s assignments changed over the years, I had other opportunities to work with him and came to know him well. I learned that before his call to be an Apostle, he served as a law clerk in the United States Supreme Court, major law firm attorney, University of Chicago law professor and administrator, executive director of the research arm of the American Bar Association, BYU president, and Utah Supreme Court justice, besides serving on numerous boards and committees, including as chairman of the Public Broadcasting System.

As one who made a sudden shift from lawyer to historian for the Church, I was impressed to learn how Elder Oaks responded to the call to be an Apostle. When President Gordon B. Hinckley extended the call by phone, a shocked yet humble Dallin Oaks replied, “My life is in the hands of the Lord, and my career is in the hands of His servants.”

In considering his new calling, Elder Oaks asked himself the question, “Throughout the remainder of your life, will you be a judge and lawyer who has been called to be an Apostle, or will you be an Apostle who used to be a lawyer and a judge?”

“I knew,” he wrote, “that if I concentrated my time on the things that came naturally and the things that I felt qualified to do, I would never be an Apostle. I would always be a former lawyer and judge. I made up my mind that was not for me. I decided that I would focus my efforts on what I had been called to do, not on what I was qualified to do. I determined that instead of trying to shape my calling to my credentials, I would try to shape myself to my calling.”

That was what I had to do when he, in turn, tapped me to change careers from lawyer to historian. People have said to me, “Wasn’t that a waste to work so hard through law school, only to throw it all away when the Church came calling?”

“No,” I’ve answered. “First, the legal education was not a waste. What I learned about sifting and weighing evidence to reach conclusions about the past transfers easily to history. Second, I learned to look at all sides of an issue and evaluate them fairly before reaching a conclusion. That too is an important skill for a historian.”

During my first week of law school, a professor spoke to the first-year students and said, “Next summer, some of you are going to work as clerks for senior law partners who will ask you to write memos. You will know which side of a case the lawyers are on, and you’ll be tempted to prepare memos that justify the partners’ positions. If you do that, you’ll be making a big mistake because they’ll get into court and be blindsided by opposing counsel bringing up things they didn’t know. You owe the senior partners a clear understanding of all sides of the issues.”

I carried that admonition into my work as a Church historian, and I never tried to shade the truth in the direction I thought Church leaders might like best. I always gave them the straight scoop. Elder Oaks and the other leaders appreciated and encouraged that. Sometimes Church leaders are hampered by people who try to second-guess them and won’t give them the truth or deliver honest feedback. Dallin H. Oaks graciously accepts feedback from his fellow Church leaders, from staff, and from family. He combines brilliance and humility as well as anyone I know.

Another thing I have admired about him is his work ethic. Since his youth, he has worked extremely hard, recognizing that small, steady effort day after day yields big results. I have tried to follow that pattern of hard work in my life as I’ve watched Elder Oaks grow from new Apostle to one of the senior-most Church leaders.

After decades of service, Elder Oaks was called into the First Presidency when President Russell M. Nelson became president of the Church after the death of President Thomas S. Monson. Before Elder Oaks became a member of the First Presidency, he called me into his office and asked if I would be willing to write his biography. He was careful not to pressure me, granting me every opportunity to say no gracefully. But I jumped at the opportunity.

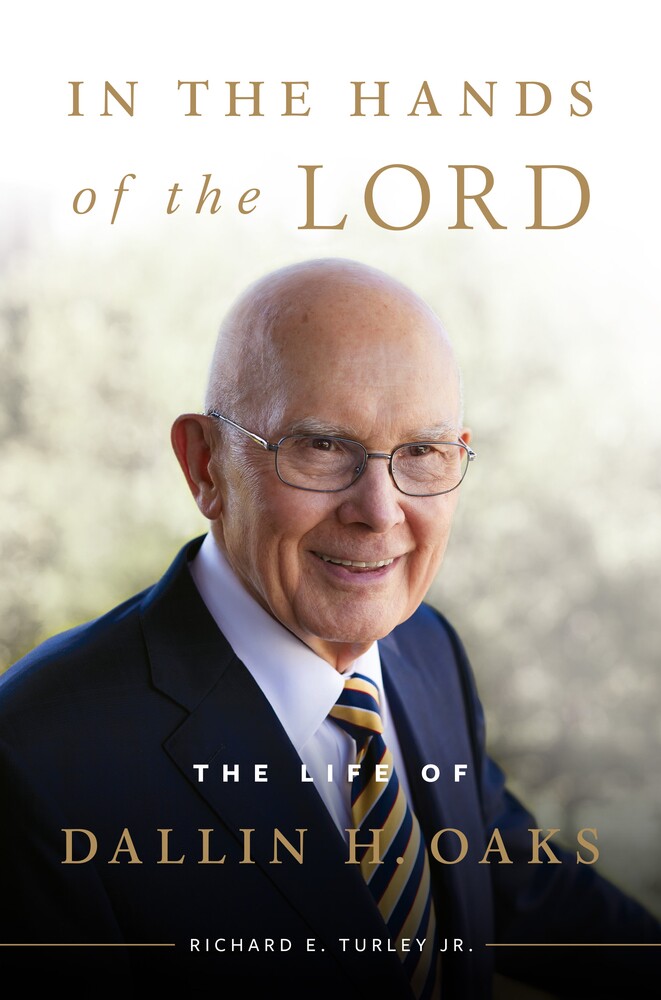

I knew he was an excellent recordkeeper and journal writer, and I knew I would enjoy studying his life from original records. He furnished his journal, correspondence, and other original records to me, and he generously made himself available whenever I needed to ask questions. We worked closely together in producing In the Hands of the Lord: The Life of Dallin H. Oaks.

Completing the biography was something that as a 15-year-old, I never dreamed I could do.