The Church’s history with race is complex and controversial. Here is a look at the priesthood and temple bans, the “curses” associated with dark skin, and the evolution of LDS beliefs and doctrine.

Even though the majority of Mormons were white in the 19th century, the white Protestant majority in America persistently suggested that they did not act or look “white” and that they were more like other marginalized racial groups. The scientific and medical communities even suggested that Mormon polygamy was spawning a new, degraded race. Ostracized for both its religious beliefs and its marital practices, the Church moved unevenly toward whiteness across the course of the 19th century in an attempt to achieve social respectability in America—an evolution that came at the expense of fellow black Saints until 1978, when the Church reversed course and returned to its racially universalistic roots.

A racially expansive vision of redemption through Jesus Christ for all of God’s children marked the early decades of the Church’s existence. One early leader, W.W. Phelps, wrote in 1835 that “all the families of the earth . . . should get redemption . . . in Christ Jesus,” regardless of “whether they are descendants of Shem, Ham, or Japeth.” Apostle Parley P. Pratt similarly professed his intent to preach “to all people, kindreds, tongues, and nations without any exception” and included India’s and Africa’s “sultry plains” in his vision of the global reach of Mormonism.

Joseph Smith received at least four revelations instructing him that “the gospel must be preached unto every creature”; these were unambiguous declarations that signaled the global mandate early Saints felt called to fulfill (see D&C 58:64; see also 68:8, 84:62, 112:28).

The universal gospel invitation initially extended all of the unfolding ordinances of the Restoration to all members. To date, there are no known statements made by Joseph Smith Jr. of a racial priesthood or temple restriction. So how did ideas about racial inequality in the Church evolve?

Whiteness in American History and Culture

Being white in American history was considered the normal and natural condition of humankind. Anything “less than” white was viewed as a deterioration from normal—a situation that made such a person unfit for the blessings of democracy. Being white meant being socially respectable; it granted a person greater access to political, economic, and social power. In the 1800s, however, “race” was a word loosely used to refer to nationality as much as skin color. People spoke of an “Irish race,” for example, and began to create a hierarchy of racial identities, with Anglo-Saxons at the top.

Mormonism was born in this era of splintering whiteness and did not escape its consequences. The Protestant majority in America was never quite certain how or where to situate Mormons within conflicting racial schemes, but they were nonetheless convinced that Mormonism represented a racial decline. Many 19th-century social evolutionists believed in the development theory: all societies advanced across three stages of progress, from savagery to barbarism to civilization.

As societies advanced, they left behind such practices as polygamy and adherence to authoritarian rule. In the minds of such thinkers, Mormons violated the development theory by practicing polygamy and theocracy—something that no true Anglo-Saxon would do. Mormons thereby represented a fearful racial descent into barbarism and savagery. Within this charged racial context, Mormons struggled to claim “whiteness” for themselves despite the fact that they were overwhelmingly of northern and western European descent.

Racialization of Mormons

The Saints’ troubled sojourns in Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois were fraught with the perception that Mormons were too open and inviting to undesirable people—blacks and Indians in particular. In 1830, the founding year of the Church, Black Pete became the first known African-American to join the faith.

Within a year of his conversion, the fact that the Mormons had a black man worshiping with them made news in New York and Pennsylvania. Edward Strutt Abdy, a British official on tour of the United States, noted that Ohio Mormons honored “the natural equality of mankind, without excepting the native Indians or the African race.” Abdy feared, however, that it was an open attitude that may have gone too far for its time and place. He believed that the Mormon stance toward Indians and blacks was at least partially responsible for “the cruel persecution by which [the Mormons] have suffered.” In his mind, the Book of Mormon ideal that “all are alike unto God,” including “black and white,” made it unlikely that the Saints would “remain unmolested in the State of Missouri.”

Other outsiders tended to agree. They complained that Mormons were far too inclusive in the creation of their religious kingdom. They accepted “all nations and colours,” they welcomed “all classes and characters,” and they included “aliens by birth” and people from “different parts of the world” as members of God’s earthly family. Outsiders variously suggested that the Mormons had “opened an asylum for rogues and vagabonds and free blacks,” maintained “communion with the Indians,” and walked out with “colored women.” In short, Mormons were charged with creating racially and economically diverse transnational communities and congregations—a stark contrast to a national culture that favored the segregation and extermination of undesirable racial groups.

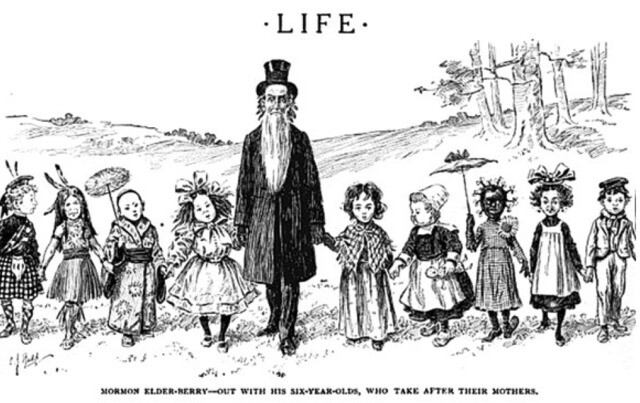

Critics began suggesting that even white Saints were physically different than other white people, and as early as the 1840s, people were speaking of a less-white “Mormon race.” Then with the open announcement of polygamy in 1852, concern among outsiders moved in a new direction: toward a growing fear of racial contamination. In the minds of outsiders, Mormon polygamy was not just destroying the traditional family—it was destroying the white race. A U.S. Army doctor reported to Congress that polygamy was giving rise to a “new race,” filthy, sunken, and degraded.

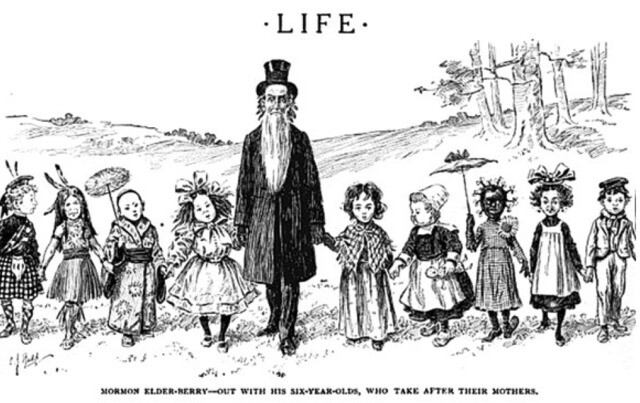

A comic pubished by Life Magazine in 1904. Image courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

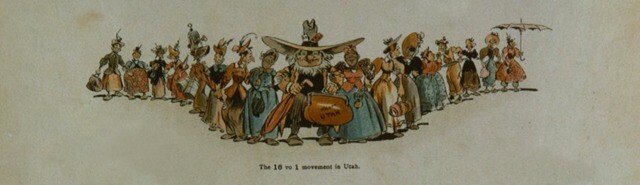

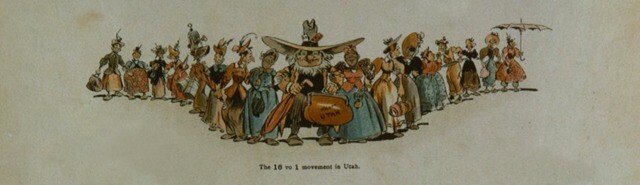

Cartoons sometimes portrayed Mormon polygamous families as interracial, and unabashedly so. In September 1896, during the presidential race between Democrat William Jennings Bryan and Republican William McKinley, Judge magazine ran one such cartoon. The illustration was titled “The 16 to 1 movement in Utah.” It used a contentious issue in the campaign that year to make fun of polygamy. Bryan advocated freeing the nation’s monetary system from the gold standard by allowing for the coinage of silver at a ratio of 16 to 1. In the Judge cartoon, however, 16 to 1 took on a new meaning in Utah: 16 women to 1 man. The polygamist man carried a bag labeled “from Utah” and stood front and center of his 16 wives, 8 on either side. It was not merely the number of women to men, however, that made the cartoon significant. It was the interracial nature of the Mormon family it depicted. The 16 wives were portrayed in a variety of shapes, sizes, and relative beauty, but it was the first wife holding the man’s left arm that was meant to unsettle its audience. She was a black woman boldly at the front of the other wives—a visual depiction of the racial corruption that outsiders worried was inherent in Mormon polygamy.

The Priesthood and Temple Restrictions Begin

At the same time that outsiders persistently criticized Mormons as facilitators of racial decline, Mormons moved in fits and starts across the course of the 19th century away from “blackness” toward “whiteness.” It is a mistake to try to pinpoint a moment, event, person, or line in the sand that divided Mormon history into a clear before and after. Rather, the policies and supporting doctrines that Church leaders developed over the course of the 19th century increasingly solidified a rationale and gave rise to an accumulating precedent that each succeeding generation reinforced, so that by the late 19th century, LDS leaders were unwilling to violate policies they mistakenly remembered beginning with Joseph Smith.

Although Brigham Young’s two speeches to the Utah Territorial Legislature in 1852 mark the first recorded articulations of a priesthood restriction by a Mormon prophet-president, it is a mistake to solely attribute the ban to seemingly inherent racism in Brigham Young. His own views evolved between 1847, when he first dealt with racial matters at Winter Quarters, and 1852, when he first publicly articulated a rationale for a priesthood restriction.

In 1847, in an interview with William (Warner) McCary, a black Mormon who married Lucy Stanton, a white Mormon, Brigham Young expressed an open position on race. McCary complained to Brigham Young regarding the way he was sometimes treated among the Saints and suggested that his skin color was a factor: “I am not a president or a leader of the people,” McCary lamented, but merely a “common brother,” a fact that he said was true “because I am a little shade darker.”

In response, Brigham Young asserted that “we don’t care about color.” He went on to suggest that color did not matter in priesthood ordination: “We have to repent and regain what we have lost,” Brigham Young insisted, “we have one of the best Elders, an African in Lowell—a barber,” he reported. Brigham Young here referred to Q. Walker Lewis, a barber, abolitionist, and leader in the black community in Lowell, Massachusetts. Apostle William Smith, younger brother to Hyrum and Joseph Smith, had ordained Lewis an elder in 1843 or 1844.

By December of 1847, however, Brigham Young’s perspective had changed. Following his expedition to the Salt Lake Valley that summer, he returned to Winter Quarters. There he learned of McCary’s interracial exploits in his absence. McCary had started his own splinter polygamous group predicated upon white women being “sealed” to him in a sexualized ritual. When his exploits were discovered, he and his followers were excommunicated. Young was also greeted with news of the marriage of Enoch Lewis, Q. Walker Lewis’s son, to Mary Matilda Webster, a white woman in the Lowell Massachusetts Branch. In response, Brigham Young spoke forcefully against interracial marriage, even advocating capital punishment as a consequence. Like Joseph Smith before him, Brigham Young opposed racial mixing and made some of his most pointed statements on the subject. Yet none of the surviving minutes from the meetings that Brigham Young held that year raise priesthood as an issue negatively connected to race. It would be five more years before Brigham Young articulated his position on that subject.

Brigham Young most fully elaborated his views in 1852 before an all-Mormon Utah Territorial Legislature as it contemplated a law to govern the black slaves that Mormon converts from the South brought with them as they gathered to the Great Basin. In fact, the very universalism of the gospel message in its first two decades created the circumstances for the restriction. Among those gathered to the Great Basin by 1852 were abolitionists and anti-abolitionists, black slaves, white slave masters, and free blacks.

In casting a wide net, Mormonism had avoided the splits or schisms that divided the Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians over issues of race and slavery during the same period. Mormonism welcomed all comers into the gospel fold, black and white, bond and free. These various people brought political and racial ideologies with them when they converted to Mormonism—ideas that initially existed independently of their faith. In 1852, however, Brigham Young prepared to instruct his diverse group of followers according to prevailing racial ideas—white over black and free over bound.

The Curse of Cain

Brigham Young tapped into long-standing biblical interpretations to draw upon Noah’s curse of Canaan, but more directly to link a racial priesthood ban to God’s purported “mark/curse” upon Cain for killing his brother Abel. “If there never was a prophet or apostle of Jesus Christ spoke it before, I tell you, this people that are commonly called Negroes are the children of old Cain. I know they are, I know they cannot bear rule in the priesthood.”

In America, as scholar David M. Goldenberg demonstrates, the idea that black people were descendants of Cain dated back to at least 1733 and in Europe to as early as the 11th century, long before Mormonism’s founding in 1830. In 1852, Brigham Young drew upon these same centuries-old ideas to both justify Utah Territory’s law legalizing “servitude” and to argue for a race-based priesthood ban.

Brigham Young insisted that because Cain killed Abel, all of Cain’s posterity would have to wait until all of Abel’s posterity received the priesthood. Brigham Young suggested that “the Lord told Cain that he should not receive the blessings of the Priesthood, nor his seed, until the last of the posterity of Abel had received the Priesthood.” It was an ambiguous declaration he and other Mormon leaders returned to time and again. It suggested a future period of redemption for blacks, but only after the “last” of Abel’s posterity received the priesthood. However, Brigham Young and other leaders failed to clarify what that meant, how one might know when the “last” of Abel’s posterity was ordained, or even who Abel’s posterity were.

Brigham Young was also departing from his own earlier position on Q. Walker Lewis’s ordination to the priesthood. And when he suggested that the priesthood was taken from blacks “by their own transgressions,” he was further creating a race-based division to cloud black redemption and make each generation after Cain responsible anew for the consequences of Cain’s murder of Abel. Although Joseph Smith rejected long-standing Christian notions of original sin to argue that “men will be punished for their own sins and not for Adam’s transgression,” Brigham Young held millions of blacks responsible for the consequences of Cain’s murder—something in which they obviously took no part.

Less Valiant in Heaven?

Even though Brigham Young and other 19th-century leaders relied upon the curse of Cain as the reason for the priesthood and temple restrictions, another explanation gained ground among some Latter-day Saints in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Because the curse of Cain so directly violated the role of individual agency in the lives of black people, some Mormons turned to the premortal realm to solve the conundrum. In this rationale, black people must have been neutral in the War in Heaven and thus were cursed with black skin and barred from the priesthood. In 1869, Brigham Young rejected the idea outright, but it did not disappear.

In 1907, Joseph Fielding Smith, then serving as assistant Church historian, argued that the teaching was “not the official position of the Church, merely the opinion of men.” In 1944, John A. Widtsoe also argued against neutrality when he said, “All who have been permitted to come upon this earth and take upon themselves bodies, accepted the plan of salvation.” Nonetheless, he argued that because black people themselves “did not commit Cain’s sin,” an explanation for the priesthood restriction had to involve something besides Cain’s murder of Abel. “It is very probable,” Widtsoe believed, “that in some way, unknown to us, the distinction harks back to the pre-existent state.”

By the 1960s, Joseph Fielding Smith slightly altered the idea, from “neutral” to “less valiant” and offered his own explanation. In his Answers to Gospel Questions, he claimed that some premortal spirits “were not valiant” in the War in Heaven. As a result of “their lack of obedience,” black people came to earth “under restrictions,” including a denial of the priesthood. The neutral/less valiant justifications grew over time to sometimes overshadow the curse of Cain explanation.

Temple Restrictions

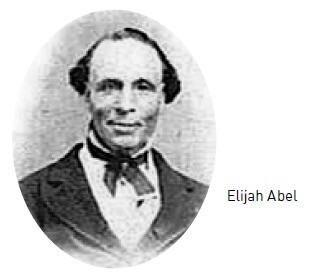

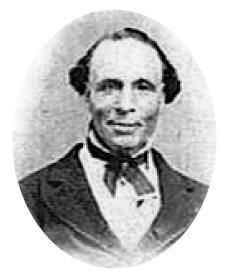

Even though black priesthood ordination officially ended under Brigham Young, it was far from a universally understood idea. In 1879, two years after Brigham Young’s death, Elijah Abel, the sole remaining black priesthood holder (Lewis had died in 1856) appealed to John Taylor for his remaining temple blessings: to receive the endowment and to be sealed to his wife. Abel had received the washing and anointing ritual in the Kirtland Temple and was baptized as proxy for deceased relatives and friends at Nauvoo but was living in Cincinnati by the time the endowment and sealing rituals were introduced.

Elijah Abel. Image from Wikimedia.

John Taylor presided over an investigation into Abel’s priesthood—an investigation that concluded that Abel was ordained an elder in 1836 and then a member of the Third Quorum of the Seventy that same year. Abel claimed that Joseph Smith himself sanctioned his ordination as an elder, and he produced certificates to verify his claims. John Taylor nonetheless concluded that Abel’s ordination was something of an exception, which was left to stand because it happened before the Lord had fully made His will known on racial matters through Brigham Young. John Taylor was unwilling to contradict the precedent established by Brigham Young, even though that precedent violated the open racial pattern established under Joseph Smith. John Taylor allowed Abel’s priesthood to stand but denied him access to the temple. Abel did not waver in his faith, though, and died in 1884 after serving three missions for the Church.

With Abel dead, Jane Manning James, another faithful black pioneer, took up the cause. She repeatedly appealed for temple privileges, including permission to receive her endowment, and asked on one occasion to be sealed to Q. Walker Lewis. She was also repeatedly denied. The curse of Cain was used to justify her exclusion. Although Church leaders did allow her to perform baptisms for dead relatives and friends and to be “attached” via proxy as a servant to Joseph and Emma Smith, she was barred from further temple access.

Between the 1879 investigation led by John Taylor and 1908 when Joseph F. Smith solidified the bans, LDS leaders adopted an increasingly conservative stance on black priesthood and temple admission. They responded to incoming inquiries by relying upon distant memories and accumulating historical precedent. Sometimes they attributed the bans to Brigham Young, and other times they mistakenly remembered them beginning with Joseph Smith. George Q. Cannon also began to refer to the Book of Abraham as a justification for the ban. As finally articulated sometime before early 1907, leaders put a firm “one drop” rule in place: “The descendants of Ham may receive baptism and confirmation but no one known to have in his veins Negro blood, (it matters not how remote a degree) can either have the priesthood in any degree or the blessings of the Temple of God; no matter how otherwise worthy he may be.”

In 1908, President Joseph F. Smith solidified this decision when he recalled that Elijah Abel was ordained to the priesthood “in the days of the Prophet Joseph” but suggested that his “ordination was declared null and void by the Prophet himself,” contradicting a statement he had made in 1895 when he reminded LDS leaders that Abel was ordained to the priesthood “at Kirtland under the direction of the Prophet Joseph Smith.” Joseph F. Smith then recalled that Abel applied for his endowments and asked to be sealed to his wife and children, but “notwithstanding the fact that he was a staunch member of the Church, Presidents Young, Taylor, and Woodruff all denied him the blessings of the House of the Lord.”

This new memory became so entrenched among leaders in the 20th century that by 1949, the First Presidency declared that the restriction was “always” in place: “The attitude of the Church with reference to Negroes remains as it has always stood. It is not a matter of the declaration of a policy but of direct commandment from the Lord.” The “doctrine of the Church” on priesthood and race was in place “from the days of its organization,” it professed. The First Presidency said nothing of the original black priesthood holders, an indication of how thoroughly reconstructed memory had come to replace verifiable facts.

Even though President David O. McKay pushed for reform on racial matters, he was convinced that it would take a revelation to overturn the ban. Hugh B. Brown, his counselor in the First Presidency, believed otherwise. Brown reasoned that because there was no revelation that began the ban, no revelation was needed to end it. McKay’s position held sway, especially as he claimed he did not receive a divine mandate to move forward. As early as 1963, however, Apostle Spencer W. Kimball signaled an open attitude for change: “The doctrine or policy has not varied in my memory,” Kimball acknowledged. “I know it could. I know the Lord could change his policy and release the ban and forgive the possible error which brought about the deprivation.” That forgiveness ultimately came with President Kimball at the helm in 1978 when he received a revelation that “every faithful, worthy man in the Church may receive the holy priesthood, with power to exercise its divine authority, and enjoy with his loved ones every blessing that flows therefrom, including the blessings of the temple. Accordingly, all worthy male members of the Church may be ordained to the priesthood without regard for race or color” (Official Declaration 2).

A Return to Equality

The 1978 Official Declaration is the only revelation in the LDS canon on priesthood and race. It returned the Church to its universalistic roots and reintegrated its priesthood and temples. It confirmed the biblical standard that God is “no respecter of persons” and the Book of Mormon principle that “all are alike unto God.”

On December 6, 2013, the Church further clarified its position with an official essay titled “Race and the Priesthood,” which was approved by the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. It states,

Today the Church disavows the theories advanced in the past that black skin is a sign of divine disfavor or curse, or that it reflects actions in a premortal life; that mixed-race marriages are a sin; or that blacks or people of any other race or ethnicity are inferior in any way to anyone else. Church leaders today unequivocally condemn all racism, past and present, in any form.

Historical and doctrinal questions not addressed in LDS Church curriculum are being widely debated and discussed online, so when Church members come across information that is unfamiliar, they may feel surprise, fear, betrayal, or even anger. This is why Laura Harris Hales has assembled a group of respected LDS scholars to offer help in A Reason for Faith: Navigating LDS Doctrine and Church History. Together these authors have spent an average of 25 years researching these complicated topics. Their depth of knowledge and faith enables them to share reliable details, perspective, and context to both LDS doctrine and Church history.

Read more about race and the priesthood and other church history topics in A Reason for Faith: Navigating LDS Doctrine and Church History, available at Deseret Book stores and deseretbook.com.

Lead image of Jane Manning James courtesy of history.lds.org