I do not come from money. I come from whatever the opposite of money is. My siblings and I joke with our parents that we are in a first world country living a third world life. Coming from humble means has made me a lot of who I am today, and it makes me grateful for even the smallest of things. But when I was younger, I didn’t have such an appreciation for my family’s meagerness. We were blessed because a lot of people served us and showed kindness, but there are experiences I have had that make it hard for me to accept service. I had a love-hate relationship with the Christmas season when I was younger. I loved focusing on the birth of the Savior, seeing the lights and all the festivity, but Christmastime was always a reminder of how poor I was and of what would not be under my family’s tree.

One year was especially thin; I was around 10 or 11, I think. We couldn’t even afford to get a Christmas tree that year. It was Christmas Eve, and we heard a knock on the door. When we opened the door, there was a tree on the front steps with presents and food all around it. I can still remember all the chatter. We just couldn’t believe it. My siblings and I were debating who this could have come from because there was no note. Some were sure it was Santa; some thought it was kind strangers. All were happy and filled with delight. We pulled everything into the house and my parents had us offer a prayer. It took forever for my parents to get us to bed that night. I just remember lying in my bed with a big ole grin on my face.

At that point, it was one of the few times in my life I had ever looked forward to waking up Christmas morning. Years of disappointment had tainted the Christmas morning buzz for me. I had long ago decided that Santa didn’t care about little black kids who lived on Johnson Ferry Road. And the last time I had sat on Santa’s lap a few years earlier, I made sure to let him know my sentiments. It must have made him mad because he and his elves brought us even less that year. After that, I figured I had better bow out of the visiting Santa thing because I didn’t want my mouth to cost everybody gifts.

That Christmas morning we said another family prayer and ate breakfast, and then finally my parents unleashed us, and we let wrapping paper fly. I don’t remember all the things I got that year, but I do remember we got a lot. One of the things I remember getting was a beautiful watch.

The following Sunday I was so excited to wear it to church. When my friends and I were sitting around chatting in Primary, people showed off a few items they were wearing that they had gotten for Christmas. I pointed out my new watch, and we all oohed and awed over each other’s presents.

Then one of the girls said to me, “Actually, you’re wearing my watch.”

“No, I’m not,” I said.

“Yes, you are,” she said. “On Christmas Eve, my parents let us open one gift, and the gift was a surprise family trip to Australia that we were leaving on that night. Then my parents asked what we wanted to do with all our Christmas presents and our tree since we wouldn’t be home for Christmas. We took a vote on if we wanted to let poor people have our tree and presents. Everyone else voted yes, but I voted no,” she said. “I wanted to open our gifts when we got back from the trip. Well, I was outvoted, so we had to give everything to your family.”

I felt as if smoke was coming out my ears. “Well, you can have your watch back,” I said, “and all the other presents, too, ’cause I don’t want them.”

“No. Mom will get mad at me,” she told me flippantly. The other girls were looking around, unsure of what to do or say. I was so humiliated! I was the poor person she had given her Christmas to—under duress. I didn’t say a word for the next two hours.

When church was over, I marched through the halls looking for one of my parents. I found my mother first. “Who gave us the stuff on the porch?” I said angrily.

“Santa,” she said.

“Really?” I said. “Because unless Santa’s real name is Brother Woolard, then I don’t think so.” I could tell from the look on my mother’s face that she knew exactly who had donated Christmas to us, and she was shocked that I knew.

“Who told you that?” she asked.

“It doesn’t matter,” I replied. “I’m never wearing this watch again, and I don’t want any of those other presents, either.”

My mother stood there confused as I stormed off to the car.

Later that night, she asked me if I was ready to tell her what had happened. When I explained my humiliating ordeal, she tried to comfort me by saying it didn’t matter who gave us the gifts. What mattered is that God helped someone to see that we were in need. She implored me to see it as a blessing.

It didn’t change how I felt, though. It was just one more reason why I knew I shouldn’t accept help from others. My young mind could only put together that people help you because they look down on you. After that, whenever a box of clothes showed up at the house and my mother tried to give me something, I would play Twenty Questions. Where did it come from? Whose is it? Why don’t they want it anymore? How do they know us? On and on and on. If I got the wrong answer to just one question, then I didn’t want whatever it was.

It’s a hard habit to break. Even as an adult I am skeptical of help. When I do have an experience of someone helping me without burning me or wanting anything in return, it sometimes still shocks me. But those shocks help to break down my walls just a little.

Yes, service makes me nervous, but it is okay to let others serve me. When I ask God for food, I would much rather it start raining manna from heaven, but that’s not how He seems to be answering prayers these days. Heavenly Father uses us to answer the prayers of our sisters and brothers. When a kind neighbor brings by a meal, that is the Lord answering my prayer. So I must humble myself, let go of my pride, and show gratitude because when I called God and God called them, they answered the call.

Lead image from Getty Images

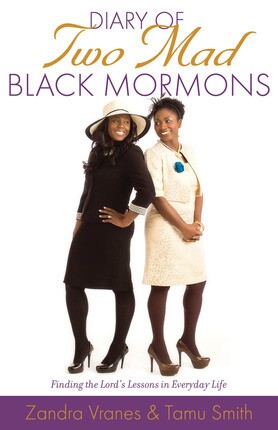

For more stories like this, check out Diary of Two Mad Black Mormons: Finding the Lord's Lessons in Everyday Life by Zandra Vranes and Tamu Smith. Available now at Deseret Book or deseretbook.com.