You have certainly seen the facsimiles from the Book of Abraham in your copy of the Pearl of Great Price, but do you know the story of the Book of Abraham? The most recent publication of the Joseph Smith Papers—Revelations and Translations, Volume 4: Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts—includes all the surviving documents related to Joseph Smith’s translation of the Book of Abraham and his study of the Egyptian language. Here are four things you may not know about that story:

The story of Joseph Smith’s involvement with ancient Egyptian artifacts actually begins with Napoleon Bonaparte.

In 1798, Napoleon invaded Egypt and took with him a cadre of scholars to document their discoveries. This effort dramatically increased Western interest in ancient Egyptian artifacts. Very quickly, this “Egyptomania” led to museums and collectors purchasing recently unearthed papyri, mummies, and other artifacts. Soon, exhibits of artifacts began touring throughout Europe and the United States.

In 1835, a man named Michael Chandler arrived in Kirtland, seeking to sell the last of a collection of artifacts brought over from Egypt. Joseph Smith and his associates purchased four mummies, two papyrus scrolls, and additional papyrus fragments, which they then began to study.

We don’t know exactly how the Book of Abraham was translated.

Unfortunately, we have no statement from Joseph Smith on the exact mechanics of the translation of the Book of Abraham. Of course, Joseph’s “translation” didn’t fit the image we often associate with that word—he had no previous knowledge of the Egyptian language and therefore couldn’t translate as a scholar would. The testimonies of his colleagues confirm that, as with the Book of Mormon, he translated “by the gift and power of God.”

The Book of Abraham translation may be best understood by understanding what we know about Joseph’s other translations. When he translated the Book of Mormon, Joseph used both the interpreters found with the gold plates and his own personal seer stone. When he approached a revision of the Bible itself (now known as the Joseph Smith Translation), Joseph looked to various resources, both divine and not, including revelation, inspiration, perhaps a seer stone, and biblical commentaries of the day. So when Joseph Smith set out to translate the papyri he had recently purchased, he had many different modes of translation on which he could draw.

The Book of Abraham was translated at two different parts of Joseph Smith’s life.

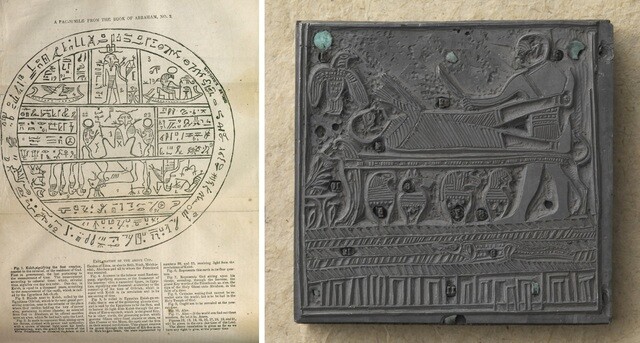

In 1835, when the papyri were acquired by the church, Joseph Smith set to work trying to decipher the Egyptian language and to dictate the Book of Abraham. By the end of 1835, he and others had moved on from their study of Egyptian to learn Hebrew (likely based on the assumption that ancient Hebrew would assist them in learning ancient Egyptian). However, the manuscripts produced in 1835 only cover what is now Abraham 1:1 through 2:18. While Joseph wanted to get back to the translation, his busy schedule and the persecution during the Saints’ stays in Kirtland and Missouri prevented any systematic work. When Joseph became editor of the Church-owned newspaper Times and Seasons in Nauvoo, Illinois, he published the Kirtland-era Book of Abraham material in the 1 March 1842 issue. According to his journal, he “commenced” translating the Book of Abraham material for the next issue (dated 15 March 1842), which constituted what is now Abraham 2:19 through the end of the book. Several issues later, the third and final “facsimile,” or illustration, from the Book of Abraham was published with a promise of more upcoming material. That promise remained unfulfilled. The Book of Abraham, as we have it, remains incomplete. There is no evidence, however, that Joseph ever translated additional material for the Book of Abraham.

The Mummies and papyri were once thought lost.

Following the death of Joseph Smith, his mother Lucy Mack Smith took full custody of the Egyptian artifacts, showing them to visitors for a fee of twenty-five cents. When Lucy died, Emma Smith Bidamon (she remarried after Joseph’s death) sold the collection of mummies and papyri to Abel Combs. He divided the collection—some of it ultimately ended up at a museum in Chicago, where it was destroyed in the great fire of 1871, and the remainder was donated to the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art in the twentieth century. Before 1967, when those fragments were transferred to the Church, many scholars thought the mummies and papyri were lost in that fire. While it appears that the mummies were, in fact, lost in the fire, the Church History Library today has several of the papyrus fragments once owned by Joseph Smith and others.

Lead images of a facsimile from the Book of Abraham and a printing plate used for publishing a facsimile from the Book of Abraham in the Times and Seasons in 1842. Both images are among the images found in Revelations and Translations: Vol. 4. Provided by Joseph Smith Papers.

Learn more with Joseph Smith Papers—Revelations and Translations, Volume 4: Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts.

This volume, the fourth in the Revelations and Translations series of The Joseph Smith Papers, includes three sets of documents: (1) the extant fragments of the papyri purchased in 1835; (2) the documents that collectively compose the "Egyptian-language documents," which are associated with the attempt by Joseph Smith and his associates to decipher hieroglyphic and hieratic characters from the papyri; and (3) the various manuscripts and first print publication of the Book of Abraham text. This facsimile edition presents full-color photographs of all these documents, with corresponding transcripts of the English text. With this unprecedented access, scholars will gain a better understanding of the physical remnants of Joseph Smith's translation process. The introductory material situates Smith's efforts in the broader context of the nineteenth-century fascination with Egyptian history and culture, of his own effort to reveal truths from the ancient past, and of his other translation efforts. The annotation in this volume explores the relationships between and among the various manuscripts. For readers interested in the textual history of the Book of Abraham, the translation process of Joseph Smith, or the way in which nineteenth-century Americans viewed Egyptian papyri, this volume's offerings will be invaluable.