“What bravery! They died with their boots on,” remarked one of the Zapatista executioners [1]. He was reflecting almost respectfully on the surreal way that Mormon leaders Rafael Monroy and Vicente Morales had stood to receive the fusillade that pierced their bodies on the evening of 17 July 1915. The terror of facing an execution squad notwithstanding, no cowering, no begging, and no hysterics marred their calm and stalwart resolution to not repudiate their faith. The Zapatista commander had given them that option. The men responded by affirming their religious convictions, emphasizing that the only arms they possessed were not the clandestine military weapons they were accused of hiding in the Monroy family store but rather their sacred texts—the Bible and the Book of Mormon—which Monroy carried with him nearly all the time. Monroy was president of the San Marcos Branch of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Vincente Morales, Monroy’s employee, was also his first counselor.

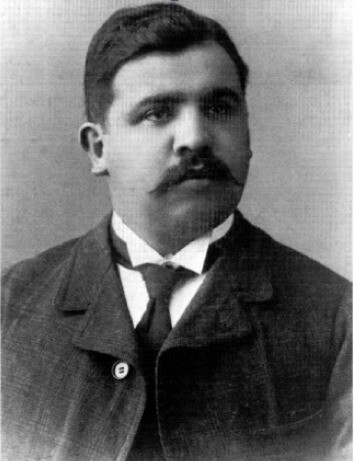

Rafael Monroy Mera (1878–1915)

When Rafael and Guadalupe’s daughter was two years old, Rafael began to develop an interest in the LDS missionary discussions. He took particular interest not only in the Book of Mormon as a compelling document but also in the Restoration’s teachings about God’s relationship with his earthly children and his requirement that they repent of their sins and be baptized.

Except for Rafael’s wife, Guadalupe, who was not happy about all this and had done her best to thwart the missionaries’ efforts, [2] the whole Monroy family was mesmerized at Joseph Smith’s hand in the Restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ and, in particular, his work in translating the Book of Mormon. Accordingly, and not surprisingly, Rafael and his sisters Guadalupe and Jovita were baptized in 1913, and soon their mother, Jesusita, joined them. Surprisingly, and despite her early foot-dragging, Rafael’s wife was also baptized a month and a half later [3]. W. Ernest Young had discharged his missionary duties well [4].

The family’s relatively good social and economic status in the community notwithstanding, Rafael, his sisters, and their mother soon felt the scimitar of persecution for having abandoned, in the eyes of their neighbors, the teachings of the community’s ancestors to join an alien U.S. church [5]. Associating with foreigners was particularly anathema to the xenophobic Zapatistas from the state of Morelos, whose armed militia would later occupy the village.

Persecution aside, the Monroy home became the Church’s meeting place for what would become a gradually increasing number of Mormons in San Marcos. Vincent Morales moved in from Puebla to help.

The rapidly assembled insurgent Zapatista firing squad that ended the life of Rafael Monroy Mera in 1915 also terminated that of his cousin-in-law, employee, and counselor in the San Marcos Branch presidency, 29-year-old Vincente Morales Guerrero.

If in the Zapatista mind a constellation of factors condemned Monroy to a firing squad (his religious persuasion being only one among several), the matter appeared to be less complicated for the Zapatista general regarding Morales. Morales was a Mormon, was therefore pairing with aliens, and was a confidant of the aspiring middle-class Monroy, who would not confess his alleged crimes, no matter the torture. Even worse, Morales would not betray Monroy by doing the confessing himself. That was enough. In those days, examination of evidence was not a hallmark of the Zapatistas’ minds except insofar as it affected their own sense of oppression and maltreatment at the hands of Mexico’s privileged classes. In the Mexican Revolution (1910–17), spiteful and indiscriminate vengeance amply fueled grief and despair as pandemonium enveloped the land like smoke from a million wildfires.

Vicente Morales Guerrero (1887–1915)

Vicente Morales was born among the indigenous Otomí in the municipality of Alfajayucan, in the state of Hidalgo [6]. He was living in Cuautla, in the state of Morelos, when he became acquainted with the Church, which he joined in 1907 at age 20. From age 17 he had been in a common-law relationship with María Petra Gutiérrez, four years his junior, with whom he had begotten and buried two daughters by 1907. After Vicente and María legalized their union through marriage to facilitate Vicente’s baptism (which must have comforted María, given she had joined the Church in Toluca at age 10), the couple had one more daughter (1909), who, like the others, died before her first birthday. In less than two years thereafter, María herself died (1911) from unrecorded causes, but perhaps related to another pregnancy.

With the family of his first love wiped out, and savaged by unremitting grief and despair, Morales nevertheless cemented himself in the Church by accepting a call as a part-time local missionary when regular missionaries fled Mexico in August 1913 due to war hostilities [7]. Given his difficulty in speaking the Spanish language (his first language being Otomí), his acceptance of a mission assignment to Spanish speakers was of itself quite remarkable. [8] His missionary efforts eventually took him to San Marcos, Hidalgo, where he made several visits. Specifically, from January to March 1914, he and his traveling companions met with the Monroy family on at least three separate occasions to give them post-baptism gospel teachings.

The civil war was displacing hundreds of thousands of people, among them many Mormons, including Casimiro Gutiérrez and Plácida González, the parents of Vicente’s deceased wife, María. Toluca, where they had been residing, was either aflame or in rubble, and Casimiro and Plácida, along with their other children, fled to San Marcos and to the community of Mormons there, hoping for safety. After the martyrdoms, Casimiro assumed the office of branch president [9], but that he and his family were in San Marcos beforehand probably encouraged Vicente to make numerous visits to his parents-in-law as the widower dealt with his grief [10].

Ultimately, however, there was perhaps a more compelling reason for Vicente to be attracted to San Marcos as a local missionary. Her name was Eulalia Mera Martínez, the 17-year-old cousin of Rafael Monroy, who was living in the Monroy compound. By mid-1914, she had taken a liking to Morales, and, within a year, that liking matured. With President Rey L. Pratt’s written permission (necessary because Vicente had a missionary calling) delivered from the United States, where he had taken refuge from the Mexican civil war, Vicente and 17-year-old Eulalia were married in San Marcos in early January 1915—just six and a half months before Morales’s execution. When the Zapatista bullets pierced Vicente’s body on 17 July 1915, his daughter Raquel was still in utero. Eulalia was five months pregnant when she heard the Zapatista fusillade that killed her husband and her cousin Rafael Monroy.

Prelude to the Martyrdom

The Monroy’s new religion was a startling viral introduction into the settled Catholic ambience of San Marcos, disturbing the village’s homeostatic equilibrium [11] and threatening to undo age-old patterns of social relations and political arrangements that ordered not only who got what but also who gave the orders and who obeyed and for what reason. Unlike in San Pedro Mártir—and perhaps Ixtacalco and several of the villages nesting at the base of the massive, picturesque, and anciently symbolic volcano Popocatépetl in central Mexico (where Mormonism took early root in the late 19th century)—Protestant versions of Christianity had not made a significant impact in San Marcos, had not, in a sense, “prepared the way” [12]. Thus, in San Marcos, Mormonism presented itself not only as a social irritant but also as a first, startling nonindigenous doctrinal competitor to Catholicism. In time, some of the village folk considered it a cancer they had to excise in order to avoid God’s calamitous judgment on the land. How else to do it but force the sinners to repent or, failing that, push them out? Or even kill them?

Thus, Mormonism’s presence in San Marcos and the increasing numbers of people embracing it merited “persecution.” These two factors—the new religion and persecution—not only isolated the early members socially but also made them vulnerable within Mexico’s frequently ad hoc arrangements for maintaining social order.

Four additional factors that contributed to the martyrdoms and their aftermath are also worthy of note: (1) The early members’ association with foreigners, especially Americans, such as the missionaries and the Tolteca cement factory’s expatriate worker team, further raised suspicions about whether the members were loyal to Mexico during the upheaval of the civil war. (2) Fueled by rampant rumormongering, the excesses of the civil war itself strained the boundaries of social restraint in San Marcos. (3) The conspicuous position of the Monroys as a relatively well-off family invited Zapatista antipathy. (4) One rabid pro-Catholic Zapatista officer commanded soldiers to assemble a firing squad that putatively legitimized a malevolent deed.

These six factors—the new religion, subsequent persecution, association with Americans, the civil war, the Monroy’s economic position, a Zapatista commander’s decision—largely explain the martyrdoms in San Marcos [13].

The Revolution Reaches San Marcos

Soon the revolution’s calamity, with its accompanying breakdown of traditional social and political order, fell upon San Marcos and the Monroy family. As elsewhere in Mexico, during this fratricidal conflict, cities, towns, and villages frequently became dueling grounds, as warring factions alternated control while each sought retribution from enemies, real or alleged. Opportunists took advantage of the anarchy to settle personal, political, and religious scores; repudiate debts; sack stores and homes; and sometimes dishonor their female occupants. It was a sad time everywhere in Mexico.

Zapatistas were at war with wealthy landowners and even Mexico’s small middle class. They were radically Catholic and fiercely xenophobic, despising foreigners for their sometimes-gratuitous attacks on their church as well as the social and economic injustices that fueled their rebellion. They detested any Mexican who associated with outsiders, and they radically opposed anyone preaching an alien religion. Small wonder the Americans feared the revolutionary Zapatistas as, indeed, apparently did most Mexicans in Hidalgo, who were anxious about their religious liberties [14]. Unfortunately for Mormons, in 1915, San Marcos briefly came under Zapatista military control [15].

Just prior to the Villista-Zapatista victory in Tula and their troops’ occupation of San Marcos, the Carrancistas had been in control there. As an occupying force, they had given appropriate guarantees to the civilian population. Nevertheless, they had made a rabid anti-Catholic statement by shelling some of the religious buildings, setting up their officers’ quarters in habitations commandeered from local clergy, and taking prisoner many Catholic priests [16]. The Zapatistas found all this to be both morally and mortally offensive [17], and they and their partisans would spare no Carrancista, no matter the cost. No wonder the Carrancista troops had retreated in terror in the face of the Villista-Zapatista alliance that was overwhelming them in Tula Hidalgo and its environs. Fittingly, many Carrancista partisans from the area bolted into the mountains.

Andres Reyes, a neighbor and one of San Marcos’s Zapatista partisans, informed the Zapatistas that Monroy routinely provisioned the Carrancista soldiers who previously had occupied the town and whom every Zapatista was sworn to kill. He also spread a profoundly false and damaging accusation that Monroy was a Carrancista officer and had a secret arms cache in his mother’s store [18]. Later, some people thought this malicious blathering was retribution for the Monroys having become Mormons [19]. The religious question was never far from people’s minds.

The accusation that Monroy was a Carrancista officer was nothing more than grist circulating in the anti-Mormon rumor mill in San Marcos at the time, perhaps resulting from a few times when Monroy did indeed fraternize with Carrancista officers. However, the accusation that he was an armed combatant was patently false.

The Executions

The Zaptistas justified the executions by taking Reyes’s rumormongering as established fact. The Zapatistas needed weapons, particularly ammunition. Reyes and other locals who wished Monroy harm told stories that resonated well. Certainly, the Monroys’ economic condition presented evidence of their being able to afford a cache, had they wanted one. Besides, they had been fraternizing with the Carrancistas and the Americans who were supporting them. The task was to extract a confession or, failing that, to dismantle the store and find the cache anyway.

Vicente Morales had been building an adobe-block partition in the store. Being more specific about his accusation, Andres Reyes suggested the weapons cache was there, somehow hidden in the partition. Zapatistas extracted Monroy from his family compound and questioned him vigorously. He and Morales denied the accusation, and Guadalupe stoutly defended both, telling the soldiers to tear the store down block by block if they did not believe her [20]. They partially obliged, ransacking the store, not finding their target but hauling off whatever they could conveniently carry.

Shortly thereafter, Zapatista soldiers detained Morales, Monroy, and Monroy’s three sisters, Natalia, Jovita, and Guadalupe. Despite dismantling the Monroy store and finding nothing, the Zapatistas were so convinced that the hidden arms cache existed somewhere that they tortured Monroy, but to no avail.

Unconvinced that Monroy was being truthful, Zapatista officers sent a new contingent of soldiers armed with sledgehammers to the Monroy store. The soldiers again ransacked the place, this time even knocking down partitions. Again finding no weapons, they moved their search to the Monroy home where a terrified Jesusita was secluded, the Zapatistas not allowing her to see her children or present evidence and witnesses to counter the accusations.

The Zapatista commander, General Reyes Molina, and some of his soldiers entered the Monroy home three times before the killings and searched every room and every piece of furniture. They wanted food from the kitchen as well as the arms, the ammunition, and papers proving that Rafael was a Carrancista colonel [21]. They found nothing. They told Jesusita that unless they received these things by 9:00 p.m. that very day, they would shoot Rafael [22]. Jesusita was apoplectic and consumed with anxiety and fear.

In the early evening of 17 July 1915, Jesusita tried once more to gain access to the prison house as she brought an evening meal to Vicente and her children. Without someone to bring meals, the prisoners did not eat—at least not often. Not permitted to enter, Jesusita left the food and returned home. Before finishing their meal, the Monroys and Vicente heard the movement of soldiers and weapons outside, followed shortly by an order for Rafael and Vicente to appear at the door and accompany them.

The Firing Squad

Presumably on orders of the local Zapatista commandant, the “sanguinary” General Reyes Molina, the soldiers marched Rafael and Vicente a short distance away, not out of earshot, probably to the hanging tree, and lined them up to be executed by gunfire. Later that evening, Rafael’s sister Guadalupe heard a soldier say that the men were offered clemency if they would repudiate their alien religion and cease to pervert the land with their ideas. Rafael and Vicente had explained that their testimony would not allow them to deny their faith. They asked to pray—a request that the executioners surprisingly allowed. The men pled with the Lord to have compassion upon their families, their unborn descendants, and even the soldiers who they said had no idea what they were doing. Afterward, Rafael stood up, folded his arms and said, “Gentlemen, I am at your service.” The shots rang out.

News of the executions quickly circulated among the Zapatista soldiers who were temporarily bivouacked in San Marcos but not involved in the slayings: “What did they find in the Monroy house?” “Why did they kill the bricklayer?” Beyond speculating on the reasons for the executions, the soldiers had trouble embracing the idea that men of such disparate social standing could equally yoke themselves in a religious brotherhood the Zapatistas ill understood, if not loathed, for its foreign origins.

The rebels’ leading light, Emiliano Zapata from the state of Morelos, today a veritable national icon in Mexico, had popularized the phrases “Land or liberty” and “Better to die on your feet than live your whole life on your knees.” All that notwithstanding, had Zapata been on the scene, he may have seen the error about to be committed in San Marcos and might have countermanded the executions that his remote commander had authorized [23].

Lead image from Wikimedia Commons

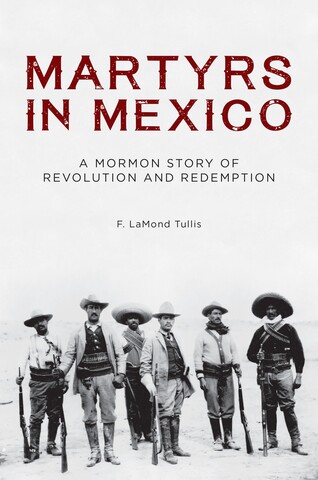

Martyrs in Mexico: A Mormon Story of Revolution and Redemption gives readers an intriguing look at the tumultuous but faith-filled experiences of the Saints seeking to establish a piece of Zion in Mexico. From the founding of the LDS Church amid revolutionary war in the late nineteenth century through the trials of organizing the faith in the state of Hidalgo into the 1950s, this book places historical Mormon figures clearly within the context of the country's society, economy, and polity. Readers will learn the background and details of how the Church survived Mexico's civil war of 1910-17, when its members were under severe duress from insurgent militias as well as their own government. Members with ties to Mexico or anyone with an interest in Church history will enjoy discovering this somewhat unknown chapter of building the kingdom.

[2] Mark L. Grover, "Execution in Mexico: The Deaths of Rafael Monroy and Vicente Morales," BYU Studies 35, no. 3 (1995-96): 7-28

[3] Walter Ernest Young, The Diary of W. Ernest Young (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1973), 107.

[4] On 11 June 1913, W. Ernest Young performed the baptisms, while mission president Rey L. Pratt witnessed the baptisms. Young, Diary, 658-60.

[5] Monroy Mera, "Como llegó el evangelio," 3-45

[6] Ruth Josefina Saunders Morales de Villalobos (daughter of Raquel Morales Mera and granddaughter of Vicente Morales) to LaMond Tullis, 11 February 2014.

[7] The call probably came from Agustin Haro, president of the San Pedro Martir Branch, which, along with the Ixtacalco Branch, undertook supervision of San Marcos when the full-time missionaries and President Rey L. Pratt fled Mexico. Monroy Mera, "Como llegó el eangelio," 7-48.

[8] Saunders Morales to Tullis.

[9] Saunders Morales to Tullis.

[10] The record does not disclose when Morales first began his missionary work in San Marcos, but he was there with his companion Juan Garcia on 25 January 1914, when they met with the Monroys.

[11] The early benchmark that solidified the biological concept of homeostasis to social system, now subsumed in cybernetics subfields, is Chalmers Johnson, Revolutionary Change, 2nd ed. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1982), especially 55-60.

[12] Monroy Mera, "Como llegó el evangelio," 108

[13] In his superb study of the executions, Mark Grover, "Executions in Mexico," 8, summarizes five factors: (1) Rafael Monroy and Vicente Morales rejected Catholocism at a time when Zapatistas were rabidly pro-Catholic; (2) Monroy's middle-class status when Zapatistas were preaching "Liberty or Death"; (3) Rafael's consorting with Americans (members and nonmembers); (4) Rafael's imputed support of the Carrancistas; and (5) the fact that Zapatistas took out their wrath indiscriminantly on medium-scale merchants.

[14] Moroni Spencer Hernández de Olarte links some members of the LDS Church, if not the Church itself, with the Zapatista movement in the state of Morelos. Bradley Hill brought this to my attention in a critique of an earlier version of this monograph.

[15] Monroy Mera, "Como llegó el evangelio," 24.

[16] The anti-Catholic policies of the Carrancistas were felt elsewhere in Mexico also. Reynaldo Rojo Mendoza, "The Church-State Conflict in Mexico from the Mexican Revolution to the Cristero Rebellion," Proceedings of the Pacific Coast Council on Latin American Studies 23 (2006): 76-96.

[17] Monroy Mera, "Como llegó el evangelio," 19.

[18] Grover, "Execution in Mexico," 15.

[19] One of the best treatments of the episodes during Monroy's last week of life is Grover's "Execution in Mexico," 6-30. I have drawn from his study for this section of the paper.

[20] Monroy Mera, "Como llegó el evangelio," 26.

[21] Monroy Mera, "Como llegó el evangelio,"26.

[22] Monroy Mera, "Como llegó el evangelio," 26.

[23] The "Liberation Army of the South," commonly known as the Zapatistas, had a loose command structure and was organized into small units, quite independent one from the other, rarely numbering more than 100 men and women (females were also combatants and held command posts), each headed by a jefe giving overall direction, did not issue field-level commands in small forays such as occurred in San Marcos. However, at the time of the executions the Zapatista San Marcos occupiers were in alliance with the Villista Tula occupiers, who may have issued the command.