Several years ago, a private Christian school asked me to present a few workshops for their faculty on the book of Job. I called my friend and mentor Dr. Robert L. Millet and asked, “What’s our best book on the book of Job?” I was hoping one of the Religious Education faculty at BYU had written a commentary.

Brother Millet responded, “We don’t have one. Go get The Bible Jesus Read by Philip Yancey. He’s a fine Christian author and editor of Christianity Today magazine.” I’m glad I did.

At one time, Philip Yancey wrote a column for Reader’s Digest magazine, a series called “Drama in Real Life.” It included stories about joggers who encountered bears, hikers who got stranded in the wilderness, or ordinary people who suddenly found themselves in the midst of a natural disaster. Philip Yancey interviewed these survivors and wrote their stories. As a Christian, he observed:

“Every single person I interviewed told me that the tragedy they had undergone pushed them to the wall with God. Sadly, each person also gave a devastating indictment of the church: Christians, they said, made matters worse. One by one, Christians visited their hospital rooms with pet theories: God is punishing you; No, not God, it’s Satan!; No, it’s God, who handpicked you to give him glory; It’s neither God nor Satan, you just happened to get in the way of an angry mother bear.

“As one survivor told me, ‘The theories about pain confused me and none of them helped. Mainly, I wanted assurance and comfort, from God and from God’s people. In almost every case the Christians brought more pain and little comfort.’” (The Bible Jesus Read [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1999], 45–46)

Perhaps we have all been guilty of trying to speculate on why others had a particular trial or were affected by an untimely death: “Well, I guess God needed them now.” Worse, we might make a judgment: “Perhaps they shouldn’t have been there,” or, “If they had been living the gospel this might not have happened.” In short, we’re giving in to our natural tendency to try to make sense of something that doesn’t make sense.

Over the years I’ve learned that as much as I’d like Him to be, God isn’t always a God of explanations. He just isn’t. At least not in this life. As Sister Sheri Dew taught, “Although the Lord will reveal many things to us, He has never told His covenant people everything about everything. We are admonished to ‘doubt not, but be believing’ [Mormon 9:27]” (Worth the Wrestle [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017], 48; emphasis added).

The book of Job is the perfect place to go for a case study of someone who was visited with problems that just plain didn’t make sense.

Job is 42 chapters long, but what happened to Job, all the bad things, happened in only six verses. A messenger bearing bad news arrives, and before he can finish talking, another messenger barges in bearing more bad news, and then another, and then another!

And there came a messenger unto Job, and said, The oxen were plowing, and the asses feeding beside them: and the Sabeans fell upon them, and took them away; yea, they have slain the servants with the edge of the sword; and I only am escaped alone to tell thee. While he was yet speaking, there came also another, and said, The fire of God is fallen from heaven, and hath burned up the sheep, and the servants, and consumed them, and I only am escaped alone to tell thee. While he was yet speaking, there came also another, and said, The Chaldeans made out three bands, and fell upon the camels, and have carried them away, yea, and slain the servants with the edge of the sword; and I only am escaped alone to tell thee. While he was yet speaking, there came also another, and said, Thy sons and thy daughters were eating and drinking wine in their eldest brother’s house: And, behold, there came a great wind from the wilderness and smote the four corners of the house, and it fell upon the young men, and they are dead, and I only am escaped alone to tell thee. (Job 1:14–19)

The book of Job begins by telling us that Job was “perfect and upright,” and that he “feared God, and eschewed evil.” Those are pretty good adjectives—not many people in the scriptures are described that way. In other words, what happened to Job didn’t make sense. Job’s response to all of his misfortune is one of the most quoted phrases in the Old Testament:

“Naked came I out of my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return thither: the Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord” (Job 1:21).

Tragedies often happen in an instant. Then we spend a lifetime trying to cope with them and figure them out. What happened to Job is covered in the first two chapters. The next thirty-five chapters are Job and his friends trying to make sense of it all. In the closing chapters of Job, the Lord finally speaks, scolding all of them for their faulty reasoning.

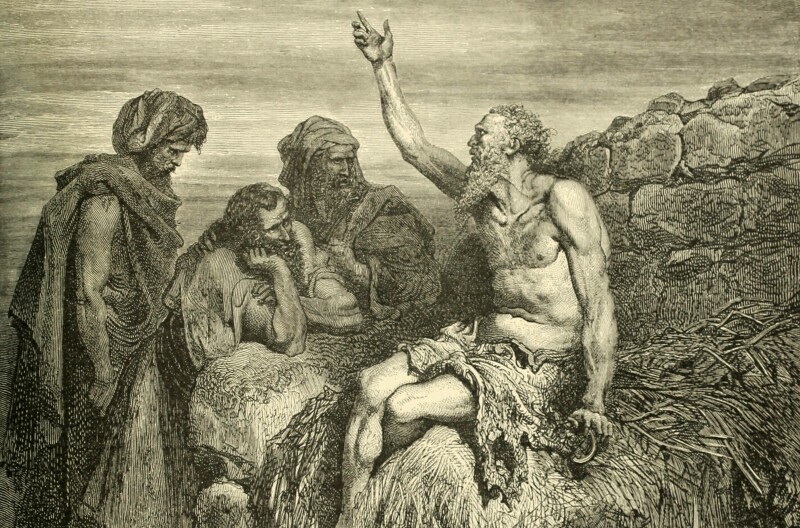

At first, Job’s friends just sat with him. No words, no talking; they just gave Job the comfort of their companionship. I love that part. Then, things got worse. As time went on, Job’s friends tried to explain why Job was suffering. In other words, they tried to force things to make sense—at least to make sense in their own minds, with their own limited, mortal understanding—with disastrous results. They drew false conclusions that caused more pain and anguish for Job and gave us an extra forty Old Testament chapters to read.

The book of Job also forces us to ask some pointed, difficult questions of ourselves: Why do we love the Lord? Well, it’s obvious! Because of all He has done for us. In just about every testimony meeting we express gratitude to God, and we should! We sing songs about God’s goodness and about how He blesses us as we count our blessings “one by one.” We sing “for the beauty of the earth” and “praise God, from whom all blessings flow.”

But the story of Job stops us in our tracks when it asks, “Do we only love God because of what He has given us?” Of course we love Him. I love God because He has been good to me. But would we love Him if He weren’t good to us? Would we love Him if He took everything away, including our possessions, our family, and our health? Could we still sing “because I have been given much, I too must give” if He had taken away everything for no reason that we could think of? Could we still love God if our suffering didn’t make sense?

Job’s response to his own suffering has given us some of the most famous and quotable lines in the whole Old Testament:

Job 1:21: “The Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord.”

Job 2:10: “Shall we receive good at the hand of God, and shall we not receive evil?”

Job 13:15: “Though he slay me, yet will I trust in him.”

Job 14:1: “Man that is born of a woman is of few days, and full of trouble.”

Job 19:25–26: “For I know that my redeemer liveth, and that he shall stand at the latter day upon the earth: And though after my skin worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh shall I see God.”

As we read the book of Job, we anticipate that in the end, it will somehow all make sense, but it doesn’t. When the Lord finally does speak, He doesn’t answer any of Job’s questions. He simply asks, “Were you there when I created everything?” and reminds Job of His power, wisdom, and grandeur. He never told Job, and He never told us, the readers of the story, why everything happened. He is not a God of explanations.

…

On a more positive note, it is interesting that God reminded Job that in the premortal world we shouted for joy at the prospect of coming into this world of trials, even the ones we couldn’t explain. Elder Neal A. Maxwell remarked:

“While most of our suffering is self-inflicted, some is caused by or permitted by God. This sobering reality calls for deep submissiveness, especially when God does not remove the cup from us. In such circumstances, when reminded about the premortal shouting for joy as this life’s plan was unfolded (see Job 38:7), we can perhaps be pardoned if, in some moments, we wonder what all the shouting was about” (“Willing to Submit,” Ensign, May 1985).

Yes, the positive message of Job is that God did answer. He didn’t explain everything, but the fact that He answered him at all shows that He was aware of Job, aware of his suffering, and aware of his struggles to make sense of it all—demonstrating that God is not a disinterested, absentee father. He did not create the world as one would wind up a clock, set it down, and then walk away only mildly interested to see what would happen with little care or concern. He heard Job, and He will hear us.

And in the end, Job got his possessions back, twofold. He got his health back, and he got new loving family relationships. And, we believe, he will be reunited in the next life with his former family who had perished. Interestingly, however, the Lord never told him why. Those kinds of answers are slow in coming. But this gives a place to begin. God is aware of us, and He knows what we’re going through. That is a good starting point when life doesn’t make sense.