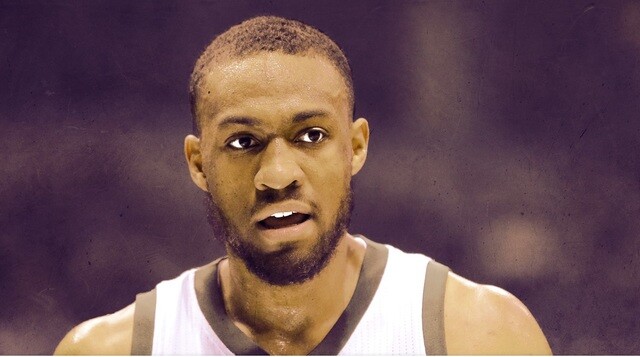

Recently, The Ringer featured Jabari Parker and his Mormon faith. Here are a few highlights from the article:

The youngest of five children, Parker awoke each day at 5 a.m. to take seminary classes for LDS youth. Then he went to school, and then Lola drove him to basketball practice. He played several years with a club team based in Indiana. Sonny believed Jabari would be well served learning fundamentals out in the country. So each day, Jabari sat in the car with his mom, doing homework as she drove.

From childhood, Parker felt different, set apart. He scheduled his basketball life around his church obligations. Some friends couldn’t fathom his Mormon faith. Others mocked him for having a father. Says Jabari: “I would hear things about how because I had a dad, I must be soft.” When he reached high school, Parker stayed home on weekend nights while friends drank or smoked. He’d been given a mission. Any lapse in focus could jeopardize his life’s work. . . .

Parker’s faith had long been a comfort and a cocoon, but now, he says, “I started to question certain things.” He learned about the LDS church’s history. Black men were long barred from entering the priesthood, until the church reversed its stance in 1978. As a famous black man with a Tongan mother and an African American father, Parker represented something of a rarity within the church. He’d never learned about this aspect of LDS history until arriving at Duke, and he struggled to reconcile the rhetoric of former church leaders with the kindness he’d experienced as a child.

“My church was in Hyde Park,” Parker says, referring to the culturally diverse neighborhood that was home to Barack Obama and the University of Chicago. “It’s a unique place. It’s different than maybe a lot of other churches. We had a lot of black people. A lot of Asian people. A lot of really liberal white people. I never once saw any discrimination. I never once felt anything like that. I grew up being in young men’s groups, and a lot of us kids were black, and a lot of the counselors were white. They never frowned on our culture. They embraced it.” He pauses for a moment. “The way I view it,” he says. “Those policies and views — they didn’t really represent God or the church. They represented those individual people who were in leadership, and people are always going to be flawed.”

As he reaffirmed his faith, Parker became intoxicated by the process of asking big questions and engaging with new ideas.