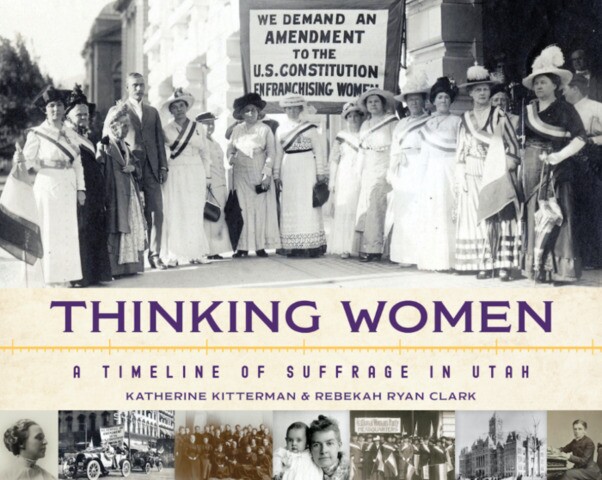

This story originally ran in the July/August 2020 issue of LDS Living.

America is celebrating some major milestones in women’s rights this year, and Utah women are at the heart of it all.

On Valentine’s Day 150 years ago, Utah women began voting. They went to the polls in a trickle at first. Then a flood. Then, an unstoppable tsunami. They were the first women in America to vote under an equal suffrage law, the very first women to choose their leaders and make their preferences known in their government.

Utah women shocked the nation when they started voting. They made the front page of newspapers across the country that day. Women did not vote in America in 1870. The idea was ludicrous. How did it happen in a rural territory in the West—where people were still struggling to grow enough food to live, still lighting tallow candles at night, and still living on the farthest edges of the United States—that women led the march toward voting equality?

The early Saints’ dedication to equal rights for women and men at the ballot is deeply tied to the faith that brought them to Utah. It grew from a belief that the Restoration of the gospel would naturally also restore women to their rightful place in families and in society. The story of Utah women’s dedication to the cause of suffrage is full of delightful twists, shocking injustices, and daring, determined characters. It’s a story that has mostly been forgotten in the 150 years since Utah women first began voting. And it’s a story that many people in Utah have joyfully rediscovered during this anniversary year.

“It Is Our Duty to Vote, Sisters”

Joseph Smith organized the women of the Church into the Relief Society in Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1842, promising that “this is the beginning of better days.” Though the organization of Relief Society disappeared for a time as the Saints moved to the Salt Lake Valley, the experience of organizing in Nauvoo would help the women of the Church through the difficult years ahead as they tried to scratch out a viable community in the desert.

For instance, when the practice of plural marriage came under attack by the United States government in the 1860s, the women of the Church were ready. Although only 40 percent of men, women, and children in Utah lived in a plural household, the practice of polygamy in Utah attracted national attention.

Laws were being proposed in Washington that would escalate the punishments for those who practiced polygamy, including confiscating Church property, forcing women to testify against their husbands, and imprisoning men who practiced polygamy.

The Relief Society responded immediately to this threat to their freedom of religion. They organized massive meetings to protest anti-polygamy laws and to assert their rights as citizens to freedom of religion—including the freedom to choose their own husbands. Tens of thousands of women in Utah attended these “indignation meetings” during the 1870s. In preparing for an indignation meeting on January 6, 1870, Bathsheba Smith declared, “We demand of the Gov the right of Franchise.” The territorial legislature of Utah, primarily made up of Latter-day Saints, acted on Smith’s statement quickly. They passed a law a month later, giving women in Utah the right to vote in February 1870. Utah governor Stephen A. Mann signed the law, and Utah became the second territory where women could vote, following Wyoming by a few weeks.

There was an election in Utah two days after the law was passed. About a dozen proud women walked to the polls on February 14, 1870. They were the first women in America to vote under an equal suffrage law.

National American Woman Suffrage Association leaders Susan B. Anthony seated in the middle, and Rev. Anna Howard Shaw standing to the left behind her with her arm reaching out to the back of her chair. Sarah M. Kimball standing directly behind Anthony looking over her glasses at the camera and Emmeline B. Wells just right of her. Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon is standing on the far left of the photo and Emily Richards is standing fourth from left. Image credit: Utah State Historical Society.

Sarah M. Kimball “had waited patiently a long time,” she told her Fifteenth Ward Relief Society sisters in a meeting a few days later. “And now that we were granted the right of suffrage,” she said in the meeting notes, “she would openly declare herself a woman’s rights woman.”

It turns out that Utah was full of women’s rights women. The Relief Society sisters taught each other the rules of parliamentary procedures and the basics of civics and government.

So that they would be better informed voters, Sarah Kimball encouraged women to read the United States Constitution six times.

In the next election in the fall of 1870, the women of Utah voted by the thousands.

Relief Society General President Eliza R. Snow, a strong advocate of women’s advancement, proclaimed to the women of the Church, “It is our duty to vote, sisters. Let no trifling thing keep you at home.”

“The Rights of the Women of Zion”

The addition of women to the electorate was highly controversial. The federal government, determined to stamp out polygamy, had hoped that Utah women—whom they believed to be oppressed—might shake the strength of the Church in Utah politics and vote against polygamist leaders like Brigham Young. When that didn’t happen, they began drafting laws to disenfranchise the women of Utah.

The famous women’s rights women of the Eastern United States, women like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, rallied around Utah women. They worked together to lobby the Congress and a few US presidents, and Stanton and Anthony even spoke in the Salt Lake Tabernacle. Utah’s leading suffragist, Emmeline B. Wells, personally met with six US presidents—Rutherford B. Hayes, Grover Cleveland, Theodore Roosevelt, James A. Garfield, Ulysses S. Grant, and Woodrow Wilson—to defend voting rights for women in Utah. She also became close friends with Susan B. Anthony.

Keeping the right to vote became an all-hands-on-deck mission for Utah women in the 1870s and 1880s. Emmeline B. Wells edited the Relief Society newspaper, the Woman’s Exponent, and filled every edition with arguments for women’s suffrage and women’s rights.

Emmeline B. Wells. Image credit: Utah State Historical Society.

“The franchise here in Utah is developing powers in women that will astonish the world,” read one editorial in the Woman’s Exponent in 1878. “We have been moderate in all things, rejoicing in our emancipation, thankfully accepting the blessing as a precious right, too precious to be trifled with.”

The masthead of the Woman’s Exponent was beautifully clear that the cause wasn’t Utah’s alone: “For the rights of the women of Zion, and the women of all nations.”

But by 1887, Congress had had enough of polygamy in Utah. They wrote the Edmunds-Tucker Act, which disincorporated The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, confiscated all of its property, and disenfranchised all Utah women—regardless of whether or not they practiced plural marriage.

The loss of the right to vote after 17 years was a heartbreak in Utah. “We were citizens of the United States, armed with that all-potent yet peaceful political weapon, the ballot, and we challenge the world to show where in a single instance we yielded it wrongfully,” read an editorial in the Woman’s Exponent.

National women’s suffrage leaders were also discouraged by this setback to their movement. The women of Utah continued to work side by side with the National Woman Suffrage Association to change people’s hearts and minds for a woman’s right to vote.

“Utah’s Glorious Star”

With no end to the opposition and political persecution in sight and after much prayer and a revelation, the president of the Church at the time, Wilford Woodruff, announced the end of polygamous marriages in 1890. When polygamy officially ended in Utah, the territory could apply to join the United States as a state. The women of Utah saw an opening to get their voting rights restored. When a group of delegates gathered in Salt Lake City in 1895 to write a constitution for the new state, women in Utah made sure that their voting rights would be irrevocably written into the law.

They signed petitions asking for their voting rights. They held large rallies for their voting rights. They asked each delegate to sign a pledge to protect their voting rights.

The debate at the constitutional convention was tense. People in Utah were anxious to have the privileges of statehood—like representation in Congress—and some delegates, like B.H. Roberts, argued that “the adoption of woman suffrage is dangerous to the acquiring of statehood.” Utah had been rejected from joining the United States in the past, and the delegates didn’t want anything to give Congress an excuse to reject them again.

Among the delegates who argued for including women’s suffrage in the constitution was Orson F. Whitney, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. “There are some things higher and dearer than Statehood,” he said. He believed that the movement of women to add their voices to the government was “one of the great levers by which the Almighty is lifting up this fallen world, lifting it nearer to the throne of its Creator.”

Franklin S. Richards, another delegate to the convention, made a striking prediction. “Equal suffrage will prove the brightest and purest ray of Utah’s glorious star,” he said.

Meanwhile, his wife, Emily S. Richards, president of the Woman Suffrage Association of Utah, was working furiously to ensure that the constitution would protect them. B.H. Roberts and other delegates had suggested that women’s suffrage could be a separate bill or a separate amendment to the state constitution, but Utah women were not going to be pushed aside when later bills and amendments could not be guaranteed. They sent petitions to each of the delegates, some with thousands of signatures. It seemed like every person in Utah wanted to weigh in on this question.

By the time the clause came up for a vote, about 25,000 signatures asked for including suffrage in the constitution while only 15,000 asked for separate submission.

Finally, it came time to vote. The delegates voted 75 to 14 for including the equal suffrage clause in the new Utah constitution. When Utah’s petition for statehood was accepted, the women of Utah won the right to vote again.

Utah Statehood pen. Image credit: Utah State Historical Society.

“Hurrah for Utah,” wrote Susan B. Anthony in a telegram to her Latter-day Saint friend, Emmeline B. Wells.

“It seems almost too good to be true that we have equal suffrage,” Wells said.

Utah entered the Union in 1896 as the third state with equal suffrage for women and men. Though there was still a long way to go to guarantee equal voting rights for many of the racial minorities in Utah, the women of Utah had achieved a landmark victory.

“She Is the Better Man”

A young doctor named Martha Hughes Cannon was the first woman to register to vote in August 1895. She had spoken up for women’s voting rights at various places, including at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, to great acclaim. Finally being able to exercise the right to vote would be a great achievement for her in a life that was already full of unusual accomplishments.

Martha “Mattie” Hughes Cannon was among the first women in the country to attend medical school. She received degrees from the University of Deseret, the University of Michigan, the University of Pennsylvania, and the National School of Elocution and Oratory.

A prominent Utah suffragist, Mattie Cannon joined the Democratic Party when Utah finally achieved statehood and ran for a seat in the Utah State Senate. Her husband, Angus M. Cannon, joined the Republican Party and also ran for a senate seat.

The Republican-leaning Salt Lake Tribune endorsed Angus, and the Salt Lake Herald responded a few days later by endorsing his wife. “Mrs. Mattie Hughes Cannon, his wife, is the better man of the two. Send Mrs. Cannon to the state senate as a Democrat and let Mr. Cannon, as a Republican, remain at home to manage home industry.”

On election day, Mattie Cannon won the seat in the Utah Senate, becoming the first woman elected as a state senator in the United States.

Cannon was not the only woman forging her way in politics. Utah women had also won seats in the Utah House of Representatives. All the women in the Utah legislature were intent on using their political power to improve society. In fact, influencing families and communities for good was a strong driver for women getting involved in politics.

The masthead of the Woman’s Exponent changed in 1897 to read: “The Ballot in the Hands of the Women of Utah should be a Power to better the Home, the State and the Nation.” Latter-day Saint women were intent on taking their new responsibilities as voters and political actors seriously.

Utah women weren’t done with the suffrage cause after they won back their right to vote. Their march toward equal rights had just gotten started, in fact. They wanted to help the women of the world to win the right, too, starting with women in the United States.

“No Sacrifice Is Too Great”

The women’s rights movement in the rest of the country had stalled by 1900. Utah women again lent their organizational skills and righteous fervor to the cause. They began collecting signatures for an amendment to the Constitution that would enfranchise all American women. They sent 40,000 signatures to Washington. They marched in parades locally and around the country. They wrote newspaper articles. They testified before the US Congress.

Even when the suffrage movement began adopting more aggressive campaigning tactics, Utah women stepped up. In 1917, the newly formed National Woman’s Party began a campaign of picketing the White House. A few Utah women grabbed banners and joined the picket line.

The banners had pointed messages asking President Woodrow Wilson to support equal voting rights. “Mr. President, How long must American women wait for liberty?” asked one banner. “Kaiser Wilson,” said another, “20,000,000 American women are not self-governed. Take the beam out of your own eye.”

Protesting the White House was unprecedented and highly controversial. Passersby sometimes spit on the women holding protest signs or threw things at them to show their disapproval of the women’s actions, though occasionally a passerby would give them food in support of their cause. President Wilson would often close his eyes as he rode past the women.

The protests in front of the White House continued for two and a half years, from January 10, 1917, to June 4, 1919. Almost 2,000 women took turns standing as “silent sentinels” outside the White House six days a week—sometimes in freezing rain, sometimes under the blazing Washington, DC, summer sun.

The two Utahns who we know participated in this controversial picketing—Minnie Quay and Lovern Robertson—were both already enfranchised. They were standing up for women outside their faith community and outside their state—women they didn’t personally know.

“I am ready to do anything within my power, and no sacrifice is too great,” said Quay.

But as time wore on, these protests grew even more unpopular. When the United States entered World War I, many people viewed the wartime protests as treason against the president.

President Wilson soon grew tired of the women standing at his front gate, and the Capitol police arrested them. They were imprisoned in Virginia and horribly mistreated. Quay reported that they were threatened with gags and told they would be tied to whipping posts. The guards threatened to shoot them. Some of the women were beaten so severely that they were hospitalized. Some went on a hunger strike and were force-fed.

When the newspapers began publishing accounts of the women’s mistreatment, public opinion began changing about the cause. President Wilson also reversed course and announced his support of an amendment to the Constitution for women’s suffrage, stating, “We have made partners of the women in this war; shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?” By 1919, Congress had written and passed an amendment.

The Utah State Legislature had a chance to vote on the constitutional amendment in the fall of 1919. The special session was a celebration of Utah women’s decades of work for equal suffrage.

The women serving in the state legislature all played a part. State Senator Elizabeth Hayward introduced a bill to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment in the Utah Senate. In the Utah House, Representative Anna T. Piercey chaired the session and Representatives Delora W. Blakely and Dr. Grace Stratton-Airey gave speeches.

Grace Stratton Airey, Woman Legislator of Utah. Image credit:Utah State Historical Society.

Utah ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on October 3, 1919. The state legislators voted unanimously for ratification.

By 1920, enough states had voted for ratification, and the US Constitution was amended so that the right to vote could not be abridged or denied on account of sex.

“America, I Love Thee”

Despite this victory, plenty of people in Utah and across the country still had to struggle for voting rights well beyond the 1920s, including Native Americans and women and men of color. And there are Utah women who have led the charge.

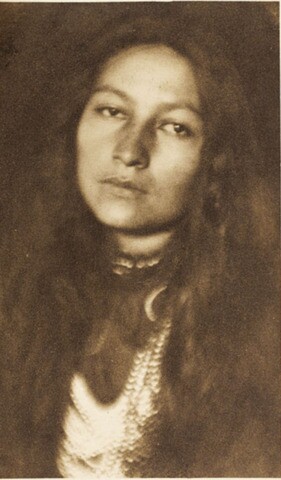

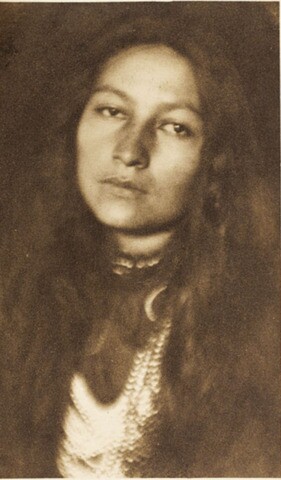

Zitkála-Šá, who lived on the Uintah-Ouray Reservation in Utah for 14 years, was a leading advocate for the rights of native peoples. She was an accomplished writer, violinist, and lecturer.

Zitkála-Šá. Image credit:Wikimedia Commons.

“We come from mountain fastness, from cheerless plains, from far-off low-wooded streams, [ . . . ] that we may stand side by side with you in ascribing honor to our nation’s flag,” Zitkála-Šá said in an oratory competition during her college years. “America, I love thee.”

One of her greatest legacies was helping European Americans acknowledge the beauty and richness of native peoples’ cultures through essays, speeches, and even an original opera. Working with a musician at Brigham Young University, Zitkála-Šá wrote the Sun Dance Opera based on a Lakota-Sioux religious ritual. The opera was performed in Utah with local Ute tribal members.

Zitkála-Šá crisscrossed the United States to advocate for native people’s rights to full citizenship. Her work bore fruit in 1924 when the Indian Citizenship Act passed.

Still, people on reservations were barred from voting in Utah and many other states. Zitkála-Šá co-founded the National Council for American Indians to bring native activists together for suffrage rights.

Ultimately, in 1957, the Utah legislature allowed Native Americans living on reservations to vote.

Utah women have played a huge role in making America a true democracy, showing the nation that women can and should participate in the larger society.

“When the Prophet Joseph Smith turned the key for the emancipation of womankind, it was turned for all the world,” President George Albert Smith observed.

We can’t include here all the women who have blazed trails for equality in Utah and across the world, but we can stand on their shoulders and carry forward their legacy of envisioning better days for women and then work hard to make those better days come.

Dianna Douglas is the creator and host of Zion’s Suffragists, a podcast about the history of women’s suffrage in Utah published by the Deseret News in conjunction with the release of Thinking Women: A Timeline of Suffrage in Utah. Find the podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, or wherever you get podcasts, or find the book at Deseret Book stores and on deseretbook.com.