Thirty years ago, students began moving into the Brigham Young University Jerusalem Center for Near Eastern Studies. Today it is considered by members and nonmembers alike to be a stunning addition to the Holy City’s landscape, but it didn’t start out that way. In fact, plans to build the Jerusalem Center caused so much controversy that the “Mormon issue” nearly caused the collapse of the Israeli government—on more than one occasion.

Located on Mount Scopus, on the northern end of the Mount of Olives, the grace and beauty of the Jerusalem Center is distinctive. With its ingenious use of space and light, and the best natural materials from around the globe, it is an architectural masterpiece that reflects the style of the Near East and makes the most of the spectacular panoramic view of the Old City below.

The beauty and serenity that permeates the Center today is a stark contrast to the events that surrounded the construction process—events which were tumultuous and fraught with opposition at nearly every turn. There were death threats, vandalism, and protest after protest. But even as the Jerusalem Center project grew into an international controversy, there were friends and supporters of many faiths who stood courageously in defense of Brigham Young University's ambitious and impressive project.

Humble Beginnings

In 1968, BYU began a study abroad program in Israel with just a handful of students renting hotel rooms. But the program quickly grew in popularity, and by 1973 Church and University leaders were considering the possibility of building a school for the students. Meanwhile, a search was underway to find land suitable for constructing a chapel for local members.

Then, on October 24, 1979, en route to the dedication of the Orson Hyde Memorial Garden—a beautifully designed park on the Mount of Olives honoring the Apostle's visit to the Holy Land in 1841—President Spencer W. Kimball announced plans to build a center in Jerusalem that would not only accommodate BYU's study abroad program, but would also serve as a multipurpose complex that would include a chapel and a visitors' center.

Elder Howard W. Hunter and Elder James E. Faust—who had been in charge of searching for land prior to the announcement—were assigned to supervise the Jerusalem Center project along with BYU President Jeffrey R. Holland. They had help from several BYU administrators, including David B. Galbraith, resident director of the study abroad program, who would later become the first executive director of the Center, and D. Kelly Ogden, an administrative assistant for BYU in Jerusalem, who would go on to become the first associate director.

During President Kimball's 1979 visit to Jerusalem, he was shown a number of possible building sites. But after walking onto a large open field north of the Orson Hyde Memorial Garden, he felt inspired that it was the spot where the Center should be built.

"I knew that site was almost certainly unavailable," recalls David B. Galbraith. "Sure enough, we were told over and over again by Israelis in real estate and government positions that it was impossible to get that site. Everyone wanted it." Even the Israeli government was eyeing the same piece of real estate to build the Supreme Court building. "But we remained undeterred," Galbraith says.

The next year was spent negotiating with Israeli officials, and ultimately the University was granted a 49-year lease for the coveted plot of land with an option to renew. "Certainly it was a miracle that the government would even entertain our desire to build on that site," Galbraith says. "We'd been told over and over again that it was hopeless."

Obtaining the lease was a huge victory, but it was just the beginning of a very lengthy process. The property was "green zoned"—not zoned for construction—so, according to Galbraith, the second miracle was getting the zoning changed. In fact, "many miracles occurred that led to the University's obtaining the most prestigious building site in all Jerusalem," D. Kelly Ogden says. And after three years of submitting plans and working to obtain all the required permits, construction began in August 1984.

The Controversy

Until this point, most Israelis were unaware of the University's plans to build, and upon seeing large bulldozers carving up the Mount, there was an immediate public outcry.

"People wondered how we got permission to build on such a site," Galbraith recalls. "Who signed off on this? How could it be that one of the last, most beautiful sites in all Jerusalem would go to a Christian group—and of all groups, the 'Mormons,' who are a proselytizing faith?"

Orthodox Jews were particularly suspicious of a church that boldly proclaimed "every member a missionary." Galbraith explains, "They insisted, despite whatever assurances we gave them, that we had an ulterior motive, that we were establishing a missionary center. And in their eyes there was great reason to be concerned—conversion of Jews to another faith is tantamount to a 'spiritual holocaust.'"

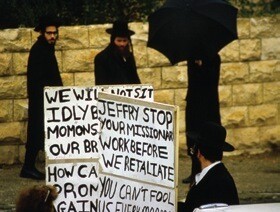

And so began nearly four years of bitter opposition. Groups who opposed the Center picketed outside the construction site, Jerusalem Mayor Teddy Kollek's office (the mayor considered the Church to be a true friend of Israel and was instrumental in helping secure the property for the Center), and even the Galbraiths' and Ogdens' homes. "They harassed us, our children at school, and threatened violence against us. They tapped our telephones," Galbraith recalls. Opponents also heavily lobbied the Israeli Knesset (the legislative branch of the Israeli government).

Once the media caught wind of the controversy, articles about the Jerusalem Center were splashed across newspapers and magazines in Israel and abroad with increasing frequency. Some warned of the impending "Mormon threat," while others presented a more fair and balanced view. As those who objected to the Center gained momentum, major television networks picked up on the story, as well as publications such as Time magazine, the New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times.

Ogden kept a detailed journal of the Jerusalem Center project from start to finish, including the fierce opposition. In his entry for July 19, 1985, he made record of one particularly large and high-profile demonstration:

Last night thousands of Orthodox Jews gathered at the Western Wall, fasting, to stage a mass protest against our "Missionary Center," as they persist in calling it. . . . CBS and NBC were also there, so we suppose that everybody in America will see it within hours. (The two networks interviewed David [Galbraith] in his home also.)

Galbraith often fielded questions from the press, granting interviews to CNN and other major news outlets. But despite his and the University's best efforts to allay fears of proselytizing and clarify the purpose of the Center, the issue became so hotly contested that the Israeli government faced no-confidence votes on three separate occasions. Since the Israeli government is a coalition government that is made up of several small parties—many of which are religious orthodox and have a great deal of political power—if a no-confidence vote had passed, the opposing parties would have caused the government to collapse by dissolving the Knesset. Luckily, the no-confidence votes were defeated.

However, in December 1985, to satisfy the opposition, Prime Minister Shimon Peres created a committee of four Cabinet ministers in favor of the Center and four Cabinet ministers opposed. The committee of eight was assigned to hold hearings and ultimately make a recommendation for or against the continued construction.

"The committee went immediately into deadlock," Galbraith recalls. "In the meantime, we just kept building."

Friends and Supporters

Despite the intense protests by Orthodox and nationalist Jews, not all Israelis opposed the construction of the Jerusalem Center. In fact, many, like Mayor Kollek, viewed the project as an opportunity to celebrate diversity and freedom of religion. Kollek, forever the peacemaker, stamped his outgoing mail with the slogan, "Let's be tolerant."

Even Jews in the U.S. weighed in on the issue. And while many were opposed to the Center like their Israeli counterparts, others rushed to defend the University's project. For example, on January 23, 1986, Rabbi Eric A. Silver, the leader of Utah's Jewish community, wrote a letter to the Knesset on behalf of the Church. He stated:

We have come to know, understand, and love our Mormon neighbors as people of the greatest decency, piety, and above all—honesty. . . . When President Holland gives his solemn assurance that the BYU Centre [sic] will not be used for missionary activity, I would stake my life on his promise, and I hasten to assure you that you can do likewise.

Less than four months later, on May 8, 1986, the United States Congress sent a letter of its own to members of the Knesset. Signed by 154 members of Congress, it reads in part:

We have become increasingly concerned by reports here in the United States concerning certain groups in Israel who have undertaken a campaign to halt the construction and use of the Brigham Young University Center for Near Eastern Studies currently under construction in Jerusalem. . . . Many of us know the sponsoring organization and the reputation of its members, and they are known as a trustworthy and moral people who live up to their promises. . . . We believe that rather than hinder U.S.-Israeli ties, the BYU Center will be a further source of understanding and cooperation between our two countries. Those students who study there will be uniquely able to teach the rest of us about your society, your culture and your rich and fascinating history. We therefore request, gentlemen, that you do all that is necessary to see that this project is allowed to be completed and occupied without undue impediments or delays.

"We had Republicans and Democrats who all lent their name and reputation. There was amazing widespread support by members of the U.S. Congress in favor of our Center," says Galbraith. Even former President Gerald Ford had sent a letter to Israeli lawmakers in favor of the project. "We were ecstatic at such a show of support," recalls Ogden.

According to Galbraith, that support was a turning point for the success of the Jerusalem Center. "In August 1986, just as the letter from Congress was having its largest effect, the ministerial committee voted in our favor. Now we were sailing—we had overcome the worst of it."

Compromise and Completion

Just as the construction seemed to be going smoothly, however, the Department of Antiquities sent a letter stating that if during the process of excavation any relics or ruins were discovered, the project must stop immediately until the findings could be investigated and permission was given to proceed - if it was ever given.

"The entire Mount of Olives is filled with tombs," says Galbraith. "We were way past the point of no return, and we were warned that our neighbors, Hebrew University, encountered many tombs during their construction process."

The Department of Antiquities assigned people to monitor the Center's excavation site daily. Remarkably, no tombs were found.

"It was yet another miracle," Galbraith says. "There is no reason that site shouldn't have been peppered with tombs." Ogden adds, "It's as though the Lord had preserved that site for us."

Just when it seemed every hurdle had been cleared, Galbraith and others were informed of a last-ditch effort to prevent BYU students from ever moving in to the Center. "Legally, once you take occupation of a building, you cannot be evicted. Someone wanted to make sure we did not take possession," he says. "Our public relations people said, 'Drop everything and just move in! Never mind that it isn't finished!' In a single day we moved in unannounced."

Luckily, the dormitories were completed, but the upper levels still were not. Barriers were put up to protect students and faculty from being injured while the construction continued.

One of the final details regarding the Jerusalem Center came when the Israeli government requested a legal document stating that the building would not be used for proselytizing purposes. "It was not an easy decision to make," says Galbraith. "Such a request singled out the Church from many other religions in Israel, so it was somewhat discriminatory in nature." But to help assure Israelis and reinforce the promises Church and University leaders had already given, in May 1988 Elder Howard W. Hunter and BYU President Jeffrey R. Holland both presented formally signed documents declaring that the Jerusalem Center would not be used for missionary activity in Israel. Finally, the "Mormon issue" was put to rest.

"In the end, strong friendships were forged through the opposition and adversity we faced," says Galbraith. "Today we have a good reputation and are well regarded by both Israelis and Palestinians. We've made our peace with most everyone."

Of Galbraith and others who pioneered the Jerusalem Center efforts, Ogden says, "Nobody in this world can know the strains and pains they endured for years to see all this through." And he includes Mayor Teddy Kollek in that group. "Through it all, he was our staunchest ally. He is the one man in Jerusalem who probably suffered most for our center being built." Despite the risk to his political career, the mayor came to tour the Center after its completion. He remarked, "I was unprepared for the beauty of this building."

On another occasion when Church leaders were in Jerusalem, Ogden recorded in his journal Elder James E. Faust's comments about the Center. Ogden wrote:

Elder Faust said, "Some have wondered if the Center hasn't required too much time, too much energy, too much money. . . . We make no apologies for this Center—how big it is, how lovely it is. . . . This is the jewel of the Holy City."

On May 16, 1989, Elder Howard W. Hunter, then president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, quietly dedicated the Brigham Young University Jerusalem Center for Near Eastern Studies with President Thomas S. Monson, Elder Boyd K. Packer, and BYU President Jeffrey R. Holland, among others, in attendance. It was done without fanfare and announced nearly a month later because the Center was still a sensitive issue for many people.

The Jerusalem Center Today

After the completion of the Center, thousands flocked to tour the facility, and thousands continue to do so today. "Word was out that when you visit Jerusalem—or if you live in Jerusalem—you ought to visit the Mormon Center," recalls Galbraith. "We never could get rid of that name. In the eyes of the Israelis, it's still the Mormon Center, even today."

People who tour the building are not allowed in the student dormitory areas, but are shown a short video about the Center, given a tour of the beautiful upper levels and the surrounding gardens, and treated to a brief organ performance while enjoying the breathtaking view. But tours aren't the only way the public can enjoy the beauty of the building. The Center also hosts art exhibits by local artists, as well as a renowned weekly concert series—and there is rarely an empty seat in the house.

"Musicians consider it a plum on their resumes to say that they have played on our stage," says S. Kent Brown, currently associate director of the Jerusalem Center. In fact, there is a long waiting list of musicians anxious for the chance to perform there.

While the public gets just a glimpse of the beauty of the facility, students studying at the Center get to savor not only the architecture, but also the fascinating and informative academic program offered within its walls. Students who participate in the study abroad program live in the Center for four months, studying the Old and New Testaments, ancient and modern Near Eastern studies, and either Hebrew or Arabic. In addition to classroom study, they enjoy numerous field trips that cover many aspects of the Holy Land—with a major focus on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ and his Apostles.

"The fundamentals of the Jerusalem Center program have remained firm through the decades," says Brown. "Only minor details have changed. The original leaders perceived that scripture would form the foundation of the program and then built a broader program from that point."

And, as always, the study abroad program strives to present a balanced view of the complex issues of the Holy Land. To help accomplish this, the Center's faculty includes Americans, Israelis, and Palestinians.

"We hire local teachers to teach not only the language classes of Hebrew and Arabic but also the classes on Islam and Judaism. We want students to see these subjects through the eyes of those who live in this society," Brown explains. In fact, the executive director of the Jerusalem Center today is Eran Hayet, an Israeli. The assistant director in charge of security, Tawfic Alawi, is Palestinian.

Meagan Knudson, who studied at the Jerusalem Center in 2008, says she gained invaluable insight and knowledge while in the Holy Land. "Learning about issues and seeing the people really broadened my view," she says. "It's made it so much easier for me to meet all kinds of different people and see different perspectives and understand where people are coming from."

She continues, "And now I have a context for scripture study. I know where events happened, and I know more about the people who lived there because we learned so much about the ancient culture. To spend so much time where the Savior lived, where he performed so many miracles, was a life-changing experience."

And this is exactly the kind of experience that Church and University leaders envisioned the students having. "We hope that, first, they return home with a brighter faith, and second, with a more informed view of the complexities of life in the Holy Land," says Brown.