The following is excerpted from Let's Talk About Religion and Mental Health.

Editor's note: We recognize that some individual experiences with anxiety can be positive, such as this, but others can be debilitating and destructive if not dealt with appropriately.

By the time the poet Emily Dickinson (1830–1886) was forty years old, she refused to leave her home and often hid in her bedroom when longtime friends came to visit. She appears to have been afflicted with agoraphobia. Other prominent people afflicted with agoraphobic anxiety include Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and actress Kim Basinger.

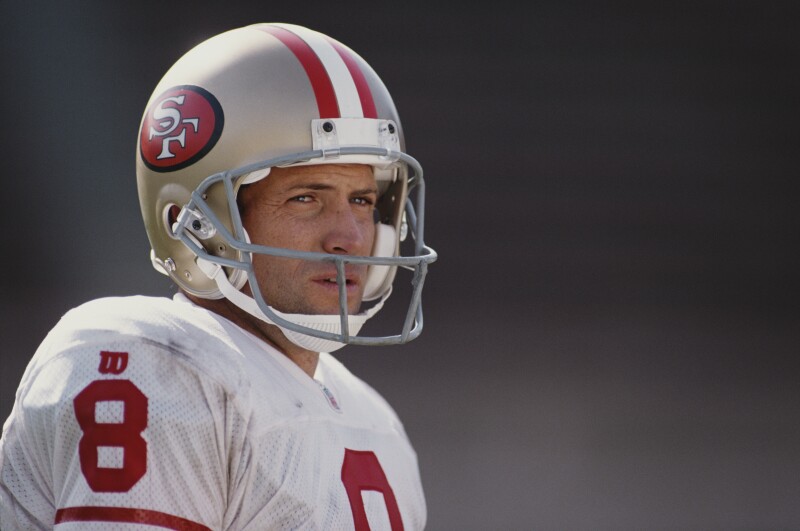

Some readers may be surprised to learn that Steve Young, Brigham Young University’s all-American quarterback, who went on to become the Super Bowl MVP while playing for the San Francisco Forty-Niners, suffered from separation anxiety disorder. His symptoms first appeared when he was a child and lasted well into his professional career in the National Football League. Anxiety—not his professional career in the NFL—was also the reason Brother Young reports that he did not serve as a full-time missionary. From Steve’s own words: “People thought my status as a football player had influenced my decision not to serve a mission, unaware that I was an eighth-string nobody [at BYU] when I made that decision. It was only the fear and anxiety that had held me back.” Brother Young explained some of what he eventually learned about his condition from the psychiatrist who initially treated him as an adult:

He [the psychiatrist] told me there was a clinical name for my symptoms: separation anxiety disorder. I had never heard this term, and I wanted to know more. He said it usually manifests itself in children when they go off to kindergarten. After five years of being nurtured, fed, and cared for exclusively by parents, some children demonstrate great anxiety when they are first put into a classroom with twenty other children and a teacher who especially functions as a new parent. “Some kids cry all day,” he explained. It’s a lot of separation anxiety. Separation anxiety was what I had as a child. Anticipatory anxiety was what I had now.

During a recent interview with Brother Young, he shared with me that one of the first nights in his life he spent away from his parents was his first night as a freshman at BYU. I asked Steve if, given the choice of living his life over again without anxiety, would he choose to do so. His answer was revealing: “My first answer is ‘yes,’ it would be awesome to go through life and just experience [it] the way everyone else did. That would be so great because I could see everyone else really enjoying the things I just couldn’t. But then here I am, and the richness that I feel, the strength, the depth that I feel. It would be different. And so in that way, I probably would get back in line for it again.”

Steve believes his experiences with anxiety have helped him become the man he is today. I found Steve Young to be a man of intellectual depth and spiritual sensitivity—born, in part, from his wrestle with anxiety. He has shown great courage in facing anxiety, and a great deal of wisdom in seeking help from his parents, family, friends, colleagues, inspired Church leaders, and mental health professionals and, above all else, “being tethered to heaven.”

. . . We should remember that life, by divine design, is intended to be difficult. Anxiety, at least in its milder forms, is one of the “thorn[s] in the flesh” (2 Cor. 12:7) we all experience and, in the end, can be a part of the mortal experience that helps us understand our need for others, including our need for and dependence on God.