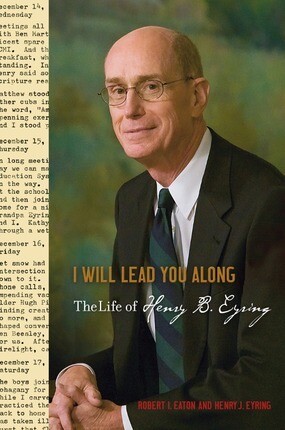

The following is an excerpt from President Henry B. Eyring's biography, "I Will Lead You Along," written by Robert I. Eaton and Henry J. Eyring.

On a Sunday several years later, when Hal was nearing the end of his physics studies at the University of Utah, Bishop Dyer invited him to his office at the church. He announced that he would soon be released as bishop to serve as president of the Church’s Central States Mission. “I’ve been called as the mission president in Independence,” Bishop Dyer said excitedly, “and I want to take you with me.”

Bishop Dyer’s declaration surprised Hal. The Korean War was in full swing, and missionary service opportunities were severely limited. In fact, for the preceding two years, 1951 and 1952, the Church had been unable to call any draft-eligible U.S. male into missionary service. It was only by special agreement with the United States government, reached by Brother Gordon Hinckley, a Church employee, that each ward could begin to send one missionary per year into the field. “I just got this permission,” Bishop Dyer exultantly told Hal. “I can send one person.”

Hal felt mixed emotions. His father, Henry, had been unable to serve a full-time mission because of his family’s indebtedness during a post–World War I economic depression. But with that immediate exception, Hal descended from some of the Church’s most faithful missionaries. His great-grandfather Henry Eyring served three full-time missions. Another great-grandfather, Miles Park Romney, twice left his family in response to mission calls. Like Mildred’s grandfather John Bennion, both of these men essentially worked as missionaries at the direction of the Brethren all their lives. The tradition of full-time mission service ran deeply in the Eyring family.

► You'll also like:President Eyring’s Humorous Call to the First Presidency: "Are You Sure You’re Talking to the Right Person?"

On the other hand, at age twenty-one, Hal assumed that the time for a mission of his own had passed. He was dating and looked forward to marrying and starting a family. Also, his ROTC commitment meant that he would have to spend two years in the Air Force, probably in Korea or Japan, immediately after graduating from college. With dozens of mission-eligible young men in Bishop Dyer’s large ward, including some exempt from military service because of physical limitations, Hal hadn’t anticipated a mission call.

Moreover, in those days mission service was admired but not expected in the Church. It would be another twenty years before President Spencer W. Kimball declared, “Certainly every male member of the Church should serve a mission.” In light of his age and military obligation, Hal felt justified in asking a fateful question. “Bishop,” he said, “I need to know something: Is it the Lord asking or just you?” Bishop Dyer paused a moment before replying, “It’s just me, Hal.”

Hal left the bishop’s office without giving a final answer. Back at home, his parents made their position clear. With a brutal land war raging on the Korean Peninsula, Mildred in particular didn’t like the thought of Hal’s dropping out of ROTC and potentially being drafted as an enlisted man after his mission; she had seen one of her friends welcome home a returned missionary son only to lose him as a casualty to the fighting in Korea. In addition, Hal’s older brother, Ted, had recently returned from an unusually difficult mission to France, where his struggles with unreceptive listeners and disobedient companions had taken a significant toll on his physical and emotional health. Mildred left the decision to Hal, but she shared her recommendation, citing an impression based on prayer: “You’re better off telling him no.”

Hal took that answer back to Bishop Dyer. “I’m sorry,” he said, “I can’t go. Give the opportunity to someone else; it’s a wonderful thing.” Bishop Dyer accepted Hal’s decision without argument.

Leaving the church building, Hal was surprised to find his uncle, Spencer Kimball of the Quorum of the Twelve, outside. Elder Kimball and his wife, Camilla, Henry’s older sister, lived just a few blocks from the Eyrings. Elder Kimball loved Henry and Mildred and their sons, whom he saw often at family gatherings. He took enough personal interest in Hal and his brothers that they felt comfortable calling him “Uncle Spencer.”

► You'll also like: When President Eyring Proved Doctors Wrong with a Prayer and a Priesthood Blessing

“What were you and the bishop talking about, Hal?” Uncle Spencer asked. Hal briefly related his discussion of mission service with Bishop Dyer.

“What did you tell him?”

“I said no, because my mother prayed and had a feeling that I shouldn’t go.”

“Well, Hal,” Uncle Spencer asked, “did you pray?”

“No,” Hal replied honestly, “but my mother’s a spiritual person, and I respect her feelings.”

“I see,” said Uncle Spencer, letting Hal go on his way without further comment.

"He didn’t say a word. He knew it was the most tragic mistake, tragic. The idea of serving a mission was everything, and he liked me. He never said a word; he just walked away. . . . Here this great man knew my heart and the way I would feel badly, but he didn’t try to turn me around that day. He could have turned me around. But he was a believer that you let people make their choice and then try to help." —2012 Interview

In the end, the decision had to be Hal’s. As he sought the guidance of the Lord, he determined to stay the course with his military commitment. He didn’t know at the time that missionary experiences would soon be coming to him in ways he hadn’t expected.

On his second Sunday in New Mexico, Hal was asked to meet with President Clement Hilton of the Church’s Albuquerque District.1 President Hilton called him to serve as a district missionary. Hal had mixed feelings about the call. It fulfilled a promise made in a blessing given before he left home. In that blessing his new bishop, Weldon Moore, had said that Hal’s military service would be his mission. Yet his military orders were clear. “I’m happy to serve,” he told President Hilton, “but I’ll be leaving in four weeks.”

“I don’t know about that,” replied President Hilton, “but we are to call you to serve.”

Suppressing his doubts, Hal accepted the call and went to work, spending the recommended ten hours each week meeting and teaching investigators.

Toward the end of his six weeks of military training, Hal was summoned by a senior military officer. Rather than being transferred, he learned, he would be staying in Albuquerque. A staff officer had unexpectedly passed away, and Hal’s physics education and performance during training had led to his being recommended to fill the open staff position. He would not only stay in Albuquerque but also work with a team of senior officers including colonels and generals from the air force, army, navy, and marines.

The most immediate benefit of this unexpected assignment was the continuation of his missionary labors. The Church in Albuquerque was small, but its district missionaries were well organized. They worked under the direction of President A. Lewis Elggren of the Western States Mission, which was headquartered in Denver. Hal ultimately received responsibility from President Elggren for a group of ten missionaries in the Albuquerque area. . . .

Hal served exactly two years as an air force officer and district missionary, deeply grateful for both opportunities. He returned home to Salt Lake City in the summer of 1957, expecting no fanfare, and was surprised to receive both a certificate of honorable release from his mission and an invitation to speak in the semiannual conference of his parents’ Bonneville Stake.

The day after the stake conference, Uncle Spencer called Hal and invited him to come to his home. They met in the little study that was famous among the neighbors for typically having a light on late at night. . . .

Elder Kimball was suffering from throat cancer; within a month he would go under the knife to have the malignancy removed, along with all of one vocal cord and part of another. Uncle and nephew sat knee to knee. “Hal,” Uncle Spencer whispered, “I want you to tell me about your experience in the military.” As Hal described what he had been doing for the past two years, Uncle Spencer expressed greatest interest in his missionary labors. He asked his nephew to relate stories of investigators and missionary companions. He wanted to learn the details of each person and the work that Hal did with him or her. They talked for an hour. Finally, Uncle Spencer seemed satisfied. “Hal,” he said solemnly, “as long as you live, when you’re asked if you’ve served a mission, you say ‘yes.’”

Learn more about Henry B. Eyring's life in I Will Lead You Along: The Life of Henry B. Eyring.