"After All We Can Do"

A common distortion of the doctrine of grace is the view that the Savior extends his grace to us only after we've done all we possibly can do. It would follow then that since no one ever really does all they possibly, theoretically could have done, no one can ever really be worthy of grace either. The false logic runs like this:

1. Grace and mercy are given only to those who are worthy of it, and only after they have proved they are worthy.

2. Only those who keep all the commandments of God all the time are really worthy.

3. But I can't keep all the commandments all the time.

4. Therefore, I'm not really worthy and can never expect to receive grace and mercy.

This kind of thinking is merely the old demand for total perfection trying to sneak in the back door of the Church in a gospel disguise, and it mocks the Atonement of Christ by insisting that we must perfect and save ourselves before the Savior can save us, that we must first cure ourselves before we deserve to call a doctor. Such logic would make it impossible for Christ to save anyone, ever. Unfortunately, sometimes even the scripturally literate will limit their concept of grace in this way without realizing that, in the long run, it turns the doctrine of grace into salvation by works. Just as mercy isn't mercy if we deserve it, so grace isn't grace if we earn it.

There are a great many superlatives used in the scriptures and the Church to exhort the Saints and describe their obligations: all our heart, our greatest desire, our best effort, after all we can do, always, every, never, and so on. We must remember that applied to mortals these terms are aspirational—that is, they define our desires and set our goals—that in each case the circumstances of the individual determine what "all," "the best," or "the greatest" mean, and that "never," "every," or "always" are goals to be reached with the help of Christ and through his atonement.

In my opinion some of the blame for our misapplication of gospel superlatives and other similarly obsessive reasoning comes from a misunderstanding of 2 Nephi 25:23: "For we labor diligently to write, to persuade our children, and also our brethren, to believe in Christ, and to be reconciled to God; for we know that it is by grace that we are saved, after all we can do" (italics added).

At first glance at this scripture, we might think that grace is offered to us only chronologically after we have completed doing all we can do, but this is demonstrably false, for we have already received many manifestations of God's grace before we even come to this point. By his grace, we live and breathe. By grace, we are spiritually begotten children of heavenly parents and enjoy divine prospects. By grace, a plan was prepared and a savior designated for humanity when Adam and Eve fell. By grace, the good news of this gospel comes to us and informs us of our eternal options. By grace, we have the agency to accept the gospel when we hear it. By the grace that comes through faith in Christ, we start the repentance process; and by grace, we are justified and made part of God's kingdom even while that process is still incomplete. The grace of God has been involved in our spiritual progress from the beginning and will be involved in our progress until the end.

It therefore belittles God's grace to think of it as only a cherry on top added at the last moment as a mere finishing touch to what we have already accomplished on our own without any help from God. Instead the reverse would be a truer proposition: our efforts are the cherry on top added to all that God has already done for us.

Actually, I understand the preposition "after" in 2 Nephi 25:23 to be a preposition of separation rather than a preposition of time. It denotes logical separateness rather than temporal sequence. We are saved by grace "apart from all we can do," or "all we can do notwithstanding," or even "regardless of all we can do." Another acceptable paraphrase of the sense of the verse might read, "We are still saved by grace, after all is said and done."

In addition, even the phrase "all we can do" is susceptible to a sinister interpretation as meaning every single good deed we could conceivably have ever done. This is nonsense. If grace could operate only in such cases, no one could ever be saved, not even the best among us. It is precisely because we don't always do everything we could have done that we need a savior in the first place, so obviously we can't make doing everything we could have done a condition for receiving grace and being saved! I believe the emphasis in 2 Nephi 25:23 is meant to fall on the word we ("all we can do," as opposed to all he can do). Moreover, "all we can do" here should probably be understood in the sense of "everything we can do," or even "whatever we can do."

Thus, the correct sense of 2 Nephi 25:23 would be that we are ultimately saved by grace apart from whatever we manage to do. Grace is not merely a decorative touch or a finishing bit of trim to top off our own efforts—it is God's participation in the process of our salvation from its beginning to its end. Though I must be intimately involved in the process of my salvation, in the long run the success of that venture is utterly dependent upon the grace of Christ.

But When Have I Done Enough?

I have a friend who always asks at about this point, "But when have I done enough? How can I know that I've made it?" This misunderstands the doctrine of grace by asking the wrong question. The right question is "When is my offering acceptable to the Lord? When are my efforts accepted for the time being?" You see, the answer to the former question, "When have I done enough?" is never in this life. Since the goal is perfection, the Lord can never unconditionally approve an imperfect performance. No matter how much we do in mortality, no matter how well we perform, the demand to do better, the pressure to improve and to make progress, will never go away. We have not yet arrived.

In this life we are all unprofitable servants, or to use a more modern term, we are all bad investments. (See, for example, Luke 17:10; Mosiah 2:21.) From the Savior's perspective, even the most righteous among us cost more to save and maintain than we can produce in return. So if we're looking for the Lord to say, "OK, you've done enough. Your obligation is fulfilled. You've made it, now relax," we're going to be disappointed. We need to accept the fact that we will never in this life, even through our most valiant efforts, reach the break-even point. We are all unprofitable servants being carried along on the Savior's back by his good will—by his grace.

However, the Lord does say to us, "Given your present circumstances and your present level of maturity, you're doing a decent job. Of course it's not perfect, but your efforts are acceptable for the time being. I am pleased with what you've done." We may not be profitable servants yet in the ultimate sense, but we can still be good and faithful ones in this limited sense. So if we are doing what can reasonably be expected of a loyal disciple in our present circumstances, then we can have faith that our offering is accepted through the grace of God. Of course we're unprofitable—all of us. Yet within the shelter of the covenant, our honest attempts are acceptable for the time being.

In fact, there is a way we can know that our efforts are acceptable, that our covenant is recognized and valid before God. If we experience the gifts of the Spirit or the influence of the Holy Ghost, we can know that we are in the covenant relationship, for the gifts and companionship of the Holy Ghost are given to none else. This is one reason why the gift of the Holy Ghost is given—as a token and assurance of our covenant status and as a down payment to us on the blessings and glory to come if we are faithful. Paul refers to the Holy Ghost as "the earnest of our inheritance" (Eph. 1:14), a reference to "earnest money," which, though only a token payment, makes a deal binding when it changes hands. Thus the "earnest [money] of the Spirit in our hearts" (2 Cor. 1:22; 5:5) assures us of the validity and efficacy of our deal, our covenant, with God.

Do you feel the influence of the Holy Ghost in your life? Do you enjoy the gifts of the Spirit? Then you can know that God accepts your faith, repentance, and baptism and has agreed that "[you] may always have his Spirit to be with [you]." (D&C 20:77.) This is perhaps one reason why the Holy Ghost is called the Comforter, because if we enjoy that gift, we can know that our efforts are acceptable—for now—and that we are justified before God by our faith in Christ. And that is comfort indeed.

Lead image from Getty Images

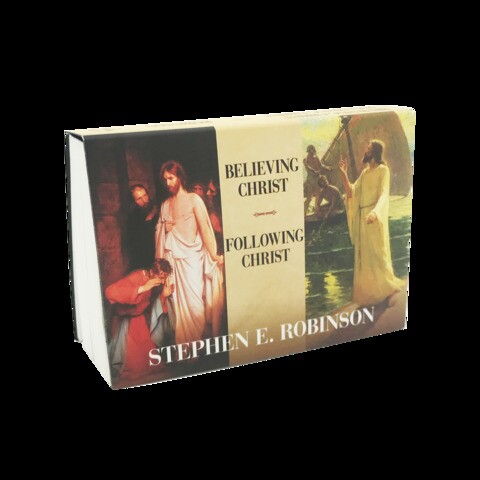

Get Believing Christ and Following Christ and other gospel classics that will fit in your pocket.

About the size of a cell phone, and with text flowing from the top page to the bottom page, these books can be read with one hand. On thin but durable paper, these books are slim and easy to pack or read on the go.

Author Stephen Robinson illustrates the power of the Savior as he uses analogies and parables, such as his own bicycle story, and scriptures and personal experiences in this moving, best-selling book. “Mortals have finite liabilities,” he explains, “and Jesus has unlimited assets.” By merging the two, exaltation can come. As long as we progress in some degree, the Lord will be pleased and will bless us. We must not only believe in Christ but also believe him — believe that he has the power to exalt us, that he can do what he claims. People will better understand the doctrines of mercy, justification, and salvation by grace after reading this book.