Twenty years ago, in the basement of my university’s library, I came across an out-of-print memoir written by World War II and Korean War veteran Ward Millar. The book’s touchstones of faith, endurance, forgiveness, sophisticated belief, and unlikely friendship touched my soul. Even as I sat in that basement, I swore that one day I would bring the story to life for a new generation.

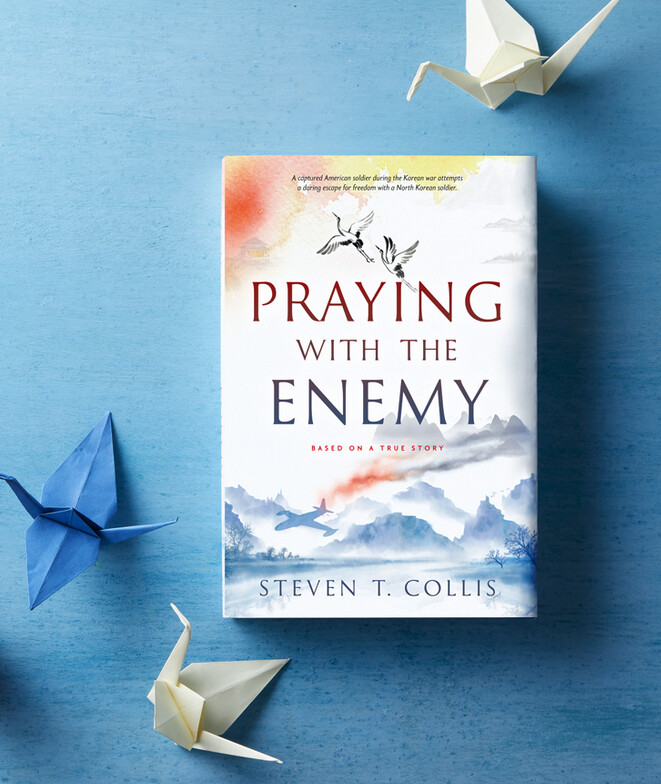

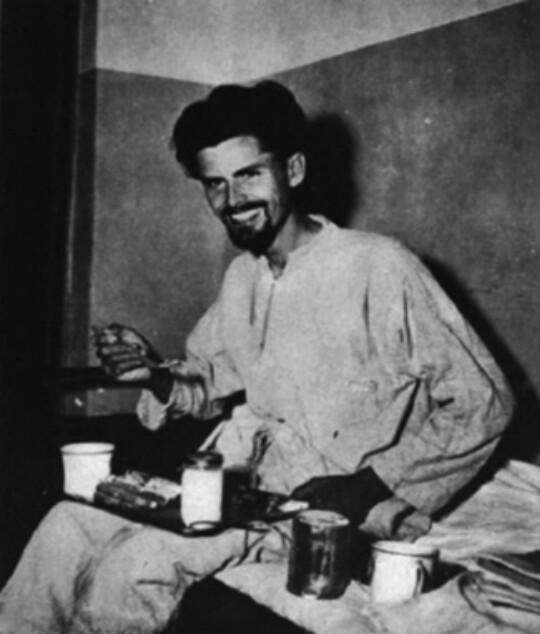

Earlier this year I made good on my promise, and my book Praying with the Enemy was published. Millar’s true story is incredible (although perhaps not as incredible as what I am about to write here): During the Korean War, Millar, an American fighter pilot, crashed behind enemy lines in North Korea. He broke both his ankles when he ejected and was captured and interrogated by communist soldiers.

After months of suffering, Millar finally managed to escape his prison. He hobbled and crawled across the North Korean countryside, but any path to freedom eluded him. Eventually a North Korean soldier under orders to execute Millar on sight recaptured the hobbled American.

Any other communist soldier would have carried out the order. Many tried. But this particular North Korean held a secret. Kim Jae Pil was a closeted Christian, forced into the army of a regime determined to destroy anyone who, like him, was dedicated to any religion or ideology besides the new Communist government.

Kim’s faith outweighed his orders, and he decided to protect Millar. Ironically, Millar was unsure if there was truly a God who would ever hear his prayers, but he respected Kim, far more than any of the communists ever would. The two men learned to communicate and became friends. Then, together, they made a miraculous escape to freedom in South Korea. Millar eventually returned to his bride and toddler in Oregon, and his nascent faith grew into an important part of his life. Kim built a life in South Korea and continued to dedicate himself to his Protestant faith.

That was the true story I intended to tell. As a Latter-day Saint, I was captivated by how these men surmounted such seemingly impossible odds, nurturing and growing their faith along the way.

As I set out on my research for the book, I learned that both Kim Jae Pil and Ward Millar had passed away from illnesses related to age. But thanks to a number of connections, I was able to talk with their families and get more details of what the men experienced up to the end of their harrowing escape. I didn’t do much research on their lives after the story ended—just enough to get a broad picture of what happened to them and to give my readers an ending they deserved.

I had no idea what treasures publishing the book would yield.

The week the book launched, I arrived in Salt Lake City from my home in Austin, Texas. I faced a full day, starting with an interview about Praying with the Enemy on a local morning television show. As I sat down with the TV anchor, lights, and cameras staring at me, I figured very few people would be watching. It was midmorning on a weekday, after all, in the streaming era.

I was only on air a few minutes, but it was enough time to give an overview of the story and to tell the audience about a book signing I would be doing that night.

As soon as the interview ended, I raced to Provo for an academic conference at BYU. An explosion of meetings, speaking, lectures, and networking followed. The moment I finished speaking on my last panel, I headed back to Salt Lake for the book signing. By that point, the TV interview had all but slipped from my mind.

When I arrived at the bookstore, I shook hands with the store manager, who pulled me close and said, “There’s a woman here who wants to see you.”

“What about?” I asked.

“She has something to tell you.”

I glanced over the manager’s shoulder and spotted the woman. She looked pleasant: in her sixties, I guessed, with a warm, patient half-smile. I had never seen her in my life.

As an author who is also a law professor in the sometimes-contentious area of constitutional law, I can get a little leery when a stranger wants to talk. But I smiled, nodded to her, and said, “Could I get settled real quick, and then we can chat?” She nodded.

After a few minutes, I finally plopped into my seat and waved the woman over, apologizing for the delay.

“That’s OK,” she said. What came next stunned me.

Her name was Cindy Forbes Whipperman. That morning, her husband had left the television on after watching the early-morning news, and she went to shut it off. It was on a station and show she never watched. Just before she clicked off the power, an impression washed over her: Leave it on; you might learn something from this. So she set down the remote and went about a few morning chores.

Minutes later, my interview came on the air—the interview I was certain no one would see. She heard me mention the North Korean soldier. She froze. She dropped everything and stepped closer to the television. At that moment, nothing else mattered—just the Korean, Kim Jae Pil, and the story she was hearing.

When the interview ended, she felt her curiosity arrive at spiritual excitement. She raced to her bookshelf and snagged her old missionary journal—a journal from when she was a Latter-day Saint missionary in South Korea many years ago, decades now, in the early 1980s. It had been too long since she’d opened it. She flipped through the pages, and there it was—her account of the very same story I had just summarized on the television.

Kim Jae Pil, the Korean soldier in my book, had crossed paths with Cindy thirty years after escaping to South Korea. When Cindy met the man and heard his story, she found it so powerful that she had to write it down. And she recorded many more details about his later life than I had known.

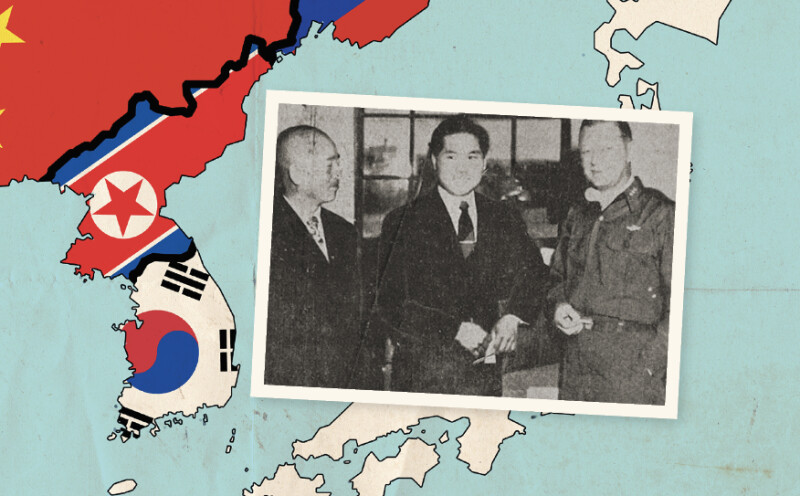

After escaping to the south with Ward Millar—a miracle in its own right—Kim was treated well by the Americans. But his fellow countrymen, the South Korean soldiers, became convinced he was a spy. They sent him to the Geoje Island prisoner of war camp, run by the United Nations. Unfortunately, the UN lacked proper control of the facility, so the camp was essentially run by Koreans.

The camp contained two hostile groups: the Communist sympathizer prisoners and the South Korean guards. Neither side accepted Kim. The Communists accused him of treason and treachery. On more than one occasion they cornered and beat him. The guards were no better—they didn’t believe his story of saving an American and defecting from the north. Far too many Communists had pretended to be defectors only to turn out to be spies. They had beaten him as well.

For months he endured this. Long after his release—long after receiving an award and a cash reward from the American military for his role in saving Ward Millar—Kim felt the wounds, the aches in his arms and back and ankles. He figured they would never leave him entirely.

More importantly, he endured the heartache of being separated from his parents and sister, still trapped in the north. He never saw them again. As the oldest son in his family, it was his traditional duty to care for his parents as they aged. The war had made that impossible. In many respects, he felt he had failed them.

That separation from his family was a tragic tale, one far too many Koreans experienced after the North’s invasion. But decades later, Kim would find an end to his sorrows.

One day, on a busy South Korean street, he met missionaries from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He had never heard of the Church before, but he listened intently. They taught him of things spiritual and unique, of events he had never learned of before. They finally reached the doctrine of temples and the notion that families can be sealed together forever, even if separated in this life. He couldn’t believe it.

He would later say that in that moment, the Spirit washed over his soul in a way he had never felt before. He knew that what he had just learned was a profound truth. He knew that he had found the way by which he could ultimately be reunited with his family.

By the time Sister Cindy Forbes Whipperman met him in Korea, Kim had been baptized. He was a faithful member of the Church and was serving in a bishopric. His children were learning the gospel. He was humble. He willingly shared his story and showed the missionaries the old scars on his legs from being knifed by the other prisoners of war. In short, he was a man Cindy would never forget.

When Cindy finished telling me her story and showing me her journal entries, I couldn’t believe it. I didn’t know anything about Kim’s conversion story until that night. Learning that he had become a faithful Latter-day Saint was a full-circle conclusion to the journey of the book I never could have imagined.

When I wrote Praying with the Enemy, I could hardly believe the odds of a closeted Christian North Korean soldier capturing an American behind enemy lines and helping him escape. By itself, that was certainly a miracle worth retelling. Today, I marvel that Kim Jae Pil met the missionaries in South Korea and joined the Church, then had a fellow Latter-day Saint stumble across his story decades later and publish it, all without knowing about Kim’s conversion. I marvel at the odds of Cindy meeting Kim Jae Pil and of her just happening to watch my three-minute midmorning interview on a TV show she never watches. But those, too, are miracles worth remembering.

I wrote my book to tell a story that needed to be told but that seemingly had no connection at all to the Church. In the end, it had a stronger bond than I possibly could have imagined.

Praying with the Enemy

When these wartime foes cross paths, they find in each other an unlikely ally. Despite speaking different languages, Millar and Kim find common ground in their fragile faith and must rely on each other to undertake a daring escape.