When I telephoned my 82-year-old mother to ask if I could write a novel about her early life, she erupted in objections. “My childhood isn’t interesting at all,” she insisted. “I can’t remember dates and places anymore, and there just aren’t enough memories to write about.” After calming her down, I persuaded my mother to let me come for a visit to explore the feasibility of the project. The dismal, wet drive from Springville, Utah, to Boise, Idaho, offered no hint of the miraculous year and a half that lay ahead.

Wounds of the Past

During the drive, I reminisced on the rocky road my mother and I had traveled. Much of my adult life was spent resentfully licking the emotional wounds from what I deemed her less-than-stellar mothering. It wasn’t until my late 40s that I matured enough to quit acting like the daughter I thought she deserved. I looked to the future and realized that in my declining years I certainly wanted my daughters to forgive my shortcomings and to love me unconditionally. I became kinder and more attentive to my mother, even though trust issues still badgered us. When she heard the gravel grinding under my tires, my mother’s frail, shrinking body shuffled onto the porch to greet me. Her eager grin multiplied the soft folds in her cheeks. For an instant, I realized how much I had missed her. I didn’t visit often enough.

After hugs and unloading my bags, I dragged the glider chair across the room to sit knee-to-knee in front of the fireplace with her. We maneuvered through small talk, and with a hesitant breath, I began my probe. Soon it was apparent we both needed an answer to the same question—could she trust me?

She was fearful that embarrassing personal or family secrets might be exposed to public scrutiny. I squirmed as I attempted to placate her fears, wondering if I believed the reassurances I was selling her. Was part of me hoping I would sniff out those unspoken stories that might further condemn the woman I had spent so many years criticizing and blaming?

Shuffling through the keepsakes in a silver metal box that she stores under her bed, my mom pulled out her mother’s old but unworn Book of Mormon. She saw the hunger in my eyes and asked if I wanted to have it. I didn’t hesitate. “Are you sure you can part with it?”

The Spirit of Elijah

My grandma Clyda had passed when I was 15, and I didn’t know her well or feel close to her. So I was startled when an unexpected feeling of awe and longing flooded me when I pressed the old book between my fingers. I couldn’t wait to retire to my bedroom that night so I could be alone to discover the hints and clues to my grandma’s heart. What verses spoke to her? What was written in the margins? What parts were read the most?

At last, I crawled into bed with keen anticipation. I drew the sacred book to my face and buried my nose in its pages, inhaling deeply. I hoped to smell the telltale scent of my grandma: Tweed perfume and Camel cigarettes. At least a faint residue of smoke still lingered.

Gingerly, I thumbed through the tissue pages, eager to discover. Squiggly red pencil lines as though a first grader had drawn them marked infrequent passages throughout the book. Suddenly, I gasped when my eyes spied the only red ink and carefully ruled underlining in the entire book:

“O wretched man that I am! Yea, my heart sorroweth because of my flesh; my soul grieveth because of mine iniquities. I am encompassed about, because of the temptations and the sins which do so easily beset me. And when I desire to rejoice, my heart groaneth because of my sins; nevertheless, I know in whom I have trusted” (2 Nephi 4:17–19).

Of course it would be Nephi’s lament that spoke to her! I could have guessed that. He sang her song. Grandma Clyda had made many poor choices in her life and suffered from depression and guilt. She became a chain-smoker and was addicted to tranquilizers most of her adult life. Much of 2 Nephi chapter four was likewise deliberately marked, but at the end of verse 31 she had double lines under this plea: “Wilt thou make me that I may shake at the appearance of sin?”

How telling. These verses captured her struggle, her heart, and what she truly longed for. I continued thumbing through each page, hoping to learn more about her. Scrawled in shaky red pencil, the word grace frequently appeared in the margins. She was desperate for grace. Knowing what I did of her sad life and overlaying it with these marked verses, I thought I sensed a bit of who she was—a woman alone, afraid, and insecure in her standing before God.

For the first time in my life, I fell asleep feeling close to my grandma. The Spirit of Elijah blanketed me as I drifted to sleep, hoping I would be with her in my dreams. She had played a big part in my mother’s life, for good and ill. I couldn’t wait to ask my mom a hundred questions the next day.

Much of the following day I spent interviewing my mother. I took notes as fast as I could when her brain sparked and the memories gushed out. I’ll never forget sitting in the kitchen across the table from my mother when it happened. Almost as an incidental FYI, she casually mentioned how she was shipped off to Catholic boarding school.

“Mom! You never told me this.”

“Well, I didn’t mean to hide it from you, dear. It just never crossed my mind.”

“It never crossed your mind to tell me that when you were 10 years old, your mom pinned a note on your coat that read, ‘Drop me off at O’Neill, Nebraska,’ and then stuck you on a train full of strangers for 10 hours?”

As more details emerged, her experience grew even more traumatic. I had to fight back my tears, but, curiously, she had none. Hers seemed locked away somewhere deep inside her little-girl heart. This was just the beginning of the endless sad and disturbing tales that I pulled from my mother’s silent past over the next several months. Her stories muted mine, and a new respect and awe grew inside me for my mother’s strength to surmount such a cruel and lonely childhood.

God Intervenes

The last day, my mission was to convince Mom to turn her journals and keepsakes over to me. After another exhausting day of memory-provoking questions and notetaking, Mom cooked her favorite recipe of fried rice for me with her secret ingredient to make it authentic (a splash of fish oil). We retired to the fireside and naturally tumbled into a long, late-night discussion about the project.

At last, the Spirit settled over us, and our hearts gave way. It wasn’t so much what was said but what was felt. Mom extended her trust, and I relinquished my questionable designs. The Lord’s merciful intervening was evident; I just felt it. This was the moment I knew He had an interest in this project; I committed to be the learner and not the designer.

I felt sober and more earnest about committing her early life to paper. I promised to call often to mine her memory for more experiences and details and to ask questions. This was going to be a tremendous undertaking. I hoped it would be worth it.

Miraculously, I returned home with a box of mom’s journals mummified in duct tape and screaming in black permanent marker, “DO NOT OPEN UNTIL I DIE!”

Curiously, the forbidden journals were not nearly as helpful as the box containing musty letters from friends and relatives and time-stained picture albums. The responsibility of finding order and truth in all this material weighed on my shoulders. I had all the physical evidence of her life in one room of my house. How would I tell her story? How could I discover the truth and not allow my biases and judgments to taint the reality?

The Process

One of the first things I did was to study the pictures in her albums and remove those that spoke to me and typified her life. I grouped them on my office wall in chronological order. It was fascinating how those paper images transformed the feeling in the room. It was as though the physical likenesses invited a spiritual presence.

As I typed away, I often stopped to stare into the faces of the children who would become my mother, my grandmother with a perpetual sadness behind her eyes, and my great-grandparents who raised my mother on their farm until she was 9 years old. I imagined how each of them felt, spoke, and loved. I guessed at their fears and dreams. Slowly, their personalities emerged, and the peculiarities of their speech filled in the dialogue and details needed for the anecdotes.

To make the dialogue believable, I had to get a real sense of their 1930–40s era. I listened to period music and radio shows to immerse myself in their lives. I researched the products they used, Google Earthed where they lived, and read the books they had read. All this aided the shaping of dialogue. And in speaking for them, I came to know, understand, and love them.

I felt their patriotism and sacrifices during World War II hardships. They never turned a homeless traveler away that stopped in at their farm for a meal. A leftover breakfast biscuit, a slab of bacon, and a couple of eggs washed down with a tall glass of milk were always available to anyone hungry.

Over months of writing, I came to love and admire my great-grandparents. When I learned something new, I shared it with my mother. Frequently our discussions triggered her memory bank, and I’d get juicy new deposits to add to the book.

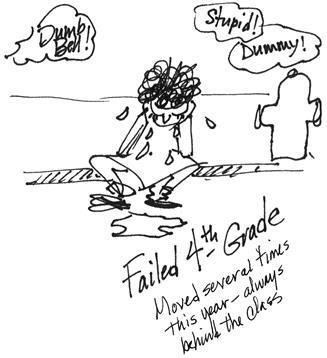

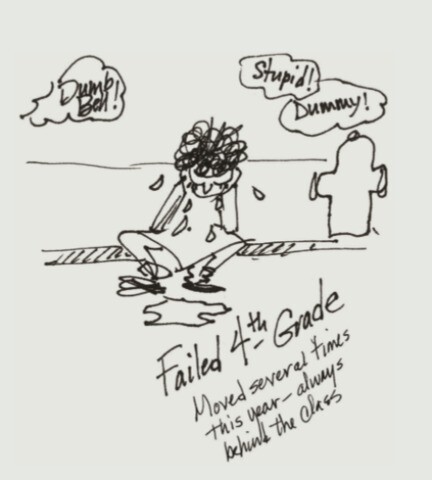

Over the months of writing, the Lord delivered many tender mercies, reassuring me that He was assisting me and that I was on the right track. As an outline of my mother’s life began to materialize with dates, places, and key events, I got the idea to ask Mom to illustrate the stories of her life. She used to enjoy sketching and painting, and I thought this would be a great addition to the book. She regretfully told me that her hands now shook too much to draw. I was sorely disappointed.

That very week, while rummaging through yet another box of my mother’s mementos, I found an artist’s journal filled with sketches of her life stories. She had drawn them many years before. I was dumbfounded and elated. The pictures were precisely what I had imagined for my book. She was as shocked as me at the discovery. She had no recollection of making those drawings, and yet there they were, just waiting to be discovered.

How I Changed

The first few months of writing I discovered that my greatest enemy was the barrage of self-defeating soundtracks that repeatedly played in my head. It sounded something like this:

You’ll never finish!

This is too hard!

Why do you think you can write?

You don’t know what you’re doing!

This writing is awful!

Just quit!

Go eat chocolate and watch a show.

I practiced disciplining my thoughts and allowed only positive affirmations to speak in my head. Like anything else, the more I practiced, the better I got at it. After just a week or two, I was able to tune in to the right station.

From a writer’s viewpoint, and practically speaking, I discovered a great key to tackling a writing project: I am the only one who can make it happen. If it fails, it fails because I did not finish the task. If it succeeds, it succeeded because I stuck with it, no matter how difficult. I told myself that if I just sat at that desk long enough, the book would someday get completed. As it turned out, that was true.

As I detailed the cruel hardships of my mother’s childhood, the bleak, omnipresent neglect of her life became undeniable. My heart ached for her, and I wept many times at my desk. I wanted to cry the tears that should have been shed for her when she suffered, but rarely was someone there to hold her and extend empathy. Sometimes my tears were for her, and other times they sprang from my shame in judging her so unfairly. But this much I know: those tears washed the pain from my heart and birthed a new love for my mother.

I wouldn’t have survived her childhood as well as she did. She is strong. She is a fighter. Once my disappointment, now my mother is my hero. In times past estranged, we are now dear friends.

Closure

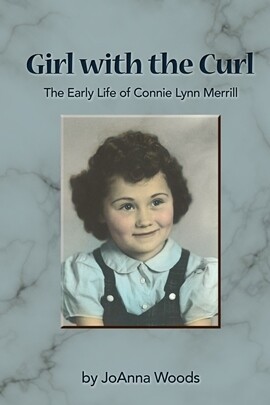

I self-published my 332-page book, titled Girl with the Curl, in the spring of 2017 and had the thrill of putting it in the hands of family members and friends. I asked my mother to read it through and tell me what she learned from it. Her answer couldn’t have shocked me more. She said, “I learned that my mother loved me.” I suppose that’s what I learned too. My mother loved me. I just didn’t see it until I learned her whole story, experienced her life. I am forever grateful to God for helping me to write the novel that repaired our breach while my mother still lives.

Photos courtesy of JoAnna Woods