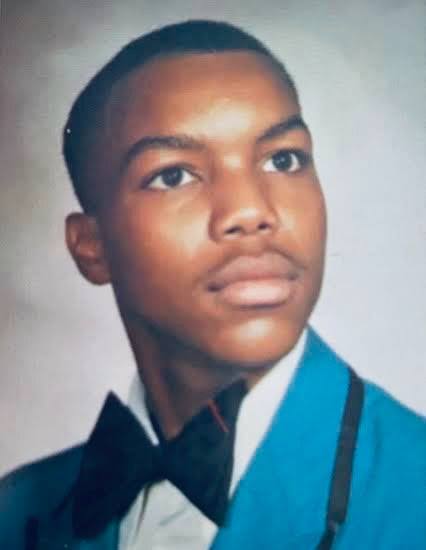

It was the end of tenth grade for me at John Bartram High School, a tough inner-city school in West Philadelphia with a student population that was about 90 percent Black. My siblings and I, like the other kids in our neighborhood, would enjoy a hot city summer. Water gushed from fire hydrants to cool off kids in cutoff shorts, and the sweltering heat rippled in waves from the softened asphalt of the black streets.

Our neighborhood was hot in other ways too. “Black fever” ran high. It was 1978. These were the days of “Black power” and “Black pride.” Slogans, music, and movies extolled the Blackness of our identities and heritage, pushing back on not only decades of discrimination against Black people but, more subtly, on the shame some Black people themselves felt about aspects of their own racial heritage. For our family, these feelings of heritage and the ability to not follow the crowd in the Black community were amplified by our interest in the Nation of Islam. We seemed odd to some who lived in ways we understood were self-destructive.

Crime, too, was heating up, as it did every summer. It was at once predictable and random in the City of Brotherly Love. And some of it was racial. When my Black friends and I walked home from school, it was not unusual for us to be chased by gangs of white youth with sticks and bricks and shouts of racial epithets as we passed through their all-white neighborhoods. We had similar problems with some Black youth as we passed through their areas or when they came into ours.

Dad had grown up in Harlem, and our family had faced challenges in the Philadelphia housing projects and row-home communities we lived in, so we had to be fairly street smart. But we were also taught to be appropriate and sensible. Mom always said our family had purpose. She kept a tight leash on us, not just to keep us alive but to help us succeed. To us, she seemed endowed with spiritual sensitivity. On one occasion, my older brother, Tony, wanted to go to a party just up the street on our block with his friend Eric, who lived across the street. Mom said “the Holy Ghost” told her she should not let him go. Of course, he became very upset. The denial did seem ridiculous given how close the party was and the fact he’d be with his friend. But she prevailed, and Tony angrily stayed in for the evening. The next day we were all shocked to hear Eric had been shot going home from the party. He was paralyzed from the waist down and died a few years later. Mom, whose credibility soared, had many similar experiences. She taught us to seek the guidance of God’s Spirit and to follow His will.

Given this training, the spiritual experience I had that same summer seems fitting in hindsight, though it was something of a surprise at the time. I had been wondering if there really was a God. My desire to know Him and if He existed was intensifying. It was then that I had a vivid dream that remains one of the most significant and sacred of my life.1

It confirmed God’s reality and set me on a path toward knowing Him. I felt so summoned by God through the dream that I arose early the next morning, a Sunday, determined to get closer to Him. I put on slacks and a dress shirt and walked to the nearest church.

The service was a Catholic mass in a traditional stone church, called Most Blessed Sacrament, two blocks away. Surprisingly, turnout was low and white. It seemed I was the only Black person there, joining longtime parishioners who now commuted from safer neighborhoods. I was also surprised by how comfortable I was with this racial dynamic. While many white individuals had had positive influence on my life, I had never worshipped with them. Given the decidedly Black Nation of Islam and our later membership in the Black Protestant church in which I had been baptized, I’d simply never had the opportunity. Yet it seemed good. I distinctly remember shaking hands with an older working-class white man in a uniform during what my Catholic friends call the sign of peace.2 I remember our mutual smiles. More importantly, I remember feeling that this cross-racial display of spiritual brotherhood was right, that it was pleasing to God.

During this same period, over 2,000 miles away in Salt Lake City, Utah, fifteen leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints wrestled with a question that would significantly impact the Church, the world, and the entire human family on both sides of the veil. Although I had no idea who they were, they would profoundly change my life and my family—root and branch—as they considered their question: Should priesthood ordination be extended to all worthy male members (and thus temple blessings for all worthy members) of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, including those of African descent, from whom it had been withheld? On June 8 of that year, President Spencer W. Kimball and his counselors in the First Presidency issued the answer in an official statement:

Aware of the promises made by the prophets and presidents of the Church who have preceded us that at some time, in God’s eternal plan, all of our brethren who are worthy may receive the priesthood, and witnessing the faithfulness of those from whom the priesthood has been withheld, we have pleaded long and earnestly in behalf of these, our faithful brethren, spending many hours in the Upper Room of the Temple supplicating the Lord for divine guidance.

He has heard our prayers, and by revelation has confirmed that the long-promised day has come when every faithful, worthy man in the Church may receive the holy priesthood, with power to exercise its divine authority, and enjoy with his loved ones every blessing that flows therefrom, including the blessings of the temple. Accordingly, all worthy male members of the Church may be ordained to the priesthood without regard for race or color.3

Two years later, in 1980, my family moved from Philadelphia to southern New Jersey, where two full-time missionaries came to our home. We later learned they had fasted and prayed for direction and were led directly to our street and house. My mother felt to invite them in. We were taught by a series of missionaries, and both parents and all ten children were baptized over several years. So far, five of us have served full-time missions, including Mom after Dad passed away.4 Three of the grandchildren have now served or are serving as full-time missionaries.

Looking back, I marvel at the minimal impact the former priesthood ban had on our decisions to join the Church. At a minimum, my mother and I knew about the ban, and some members and missionaries attempted explanations before we were baptized.5 But even the ethos of that era, strongly reinforced in our family’s racial experiences, did not inhibit us from accepting and embracing the restored gospel. Our spiritual and social experiences while learning about the Church, and the testimonies that grew out of these experiences, were such that I don’t remember race being much of an issue. This was true even though our Latter-day Saint congregation was overwhelmingly white.

It was not until after I was baptized in 1980 that I seriously studied the former priesthood ban on people of African descent. That study took me on a journey that, thanks to the gospel of Jesus Christ, transcended race, ethnicity, and culture.

I think it is natural for many Black people who join or investigate The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to look into the priesthood ban. However, we should always remember that the center of our lives and therefore the focus of our study ought always to be Jesus Christ and His doctrine. No amount of study of the priesthood ban will save us from death and enable us to return to God to enjoy eternal life with our families. Only the doctrine of Christ can help us achieve these eternal goals. And, in my observation and experience, if we focus on the former to the neglect of the latter, we will stumble. As I sought to deepen my relationship with God, I found my focus and energy continually more centered on Jesus Christ and His Atonement. As I ministered to others, it became clear to me that the doctrine of Christ, especially faith in Jesus Christ and His Atonement, was the way to access the most potent source of divine power and peace for anyone struggling with anything related to the restored gospel or the Church that administers it.6

The Prophet Joseph Smith’s declaration about “the testimony of Jesus” sprang to new life for me (Revelation 19:10; see also Doctrine and Covenants 76:51). “The fundamental principles of our religion,” he said, “are the testimony of the Apostles and Prophets, concerning Jesus Christ, that He died, was buried, and rose again the third day, and ascended into heaven; and all other things which pertain to our religion are only appendages to it.”7

As my focus on Christ and His Atonement increased, the vision of Heavenly Father’s unified human family became clearer. Correspondingly, the priesthood ban and its particulars diminished in importance for me personally. I have also seen this with other Latter-day Saints who struggled with the former ban. They became converted to the restored gospel of Jesus Christ—and remained in His Church—only as they gained a personal witness and understanding of the doctrine of Christ and applied it in their lives.

The doctrine of Christ includes faith in Jesus Christ and His Atonement, repentance, baptism into The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, receiving the gift of the Holy Ghost, and enduring to the end. In my case, understanding Jesus’s Atonement changed my self-perception forever. It catapulted my identity as a child of God, a child of the covenant, a disciple of Christ, a minister of the gospel, and a brother in the human family far above even the most socially ingrained aspects of my Black identity, despite my intense racial experiences. I believe one of the ways it accomplished this was, ironically, by giving me a sense of my own nothingness without Christ. Suddenly, the principles, teachings, and experiences of prophets in the scriptures, especially the Book of Mormon and Pearl of Great Price, awakened a vision of my utter dependence upon Jesus and my dire need of His salvation and to follow Him. Far from having a problem with His Church, I saw more keenly than ever how supremely blessed I was to be a part of it and what a profound honor it was to help establish it as much as I could. This deep spiritual self-perception didn’t diminish my earthly racial identity at all. On the contrary, it contextualized and magnified it in eternity.8

Notes

- Because the dream is so sacred, it remains private to me and my family.

- In this part of the mass, attendees shake hands and wish each other peace.

- Doctrine and Covenants, Official Declaration 2.

- I was not one of those truly valiant Black Latter-day Saints who joined the Church prior to the revelation. Seven of us were baptized in 1980. Dad followed in 1981, and the oldest child was baptized in 1994. The three youngest were baptized as they came of age.

- Oddly enough, I don’t remember the moment when I learned of the priesthood restriction. While I was writing this essay, I was told by a good friend that at the time of my baptism, I asked “a lot of tough questions” about the ban. While I am sure this is true, I don’t remember it. My earliest memory of talking about the ban was when I was a full-time missionary teaching a Black man in St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands. He had served at Hill Air Force Base near Ogden, Utah, where he had heard several times about the restriction. He was incredulous that I, as a Black person, could be a Mormon. So while I don’t specifically remember struggling with the ban, early on in my Church membership it became a challenge to help others overcome so they could experience the deeper and sweeter fruits of the restored gospel that lay beyond it.

- It was about this time that I heard a talk that had a great impact on my life, “Another Testament of Jesus Christ,” by President Dallin H. Oaks. Citing the teachings of President Ezra Taft Benson, President Oaks invited the Church to repent for not remembering the Book of Mormon and its essential feature of salvation through Jesus Christ. See Ensign, March 1994.

- Joseph Smith, in Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph Smith (2007), 49.

- President James E. Faust taught: “We do not lose our identity in becoming members of this church. We become heirs to the kingdom of God, having joined the body of Christ and spiritually set aside some of our personal differences to unite in a greater spiritual cause. We say to all who have joined the Church, keep all that is noble, good, and uplifting in your culture and personal identity. However, under the authority and power of the keys of the priesthood, all differences yield as we seek to become heirs to the kingdom of God, unite in following those who have the keys of the priesthood, and seek the divinity within us. All are welcomed and appreciated. But there is only one celestial kingdom of God. Our real strength is not so much in our diversity but in our spiritual and doctrinal unity. For instance, the baptismal prayer and baptism by immersion in water are the same all over the world. The sacramental prayers are the same everywhere. We sing the same hymns in praise to God in every country” (“Heirs to the Kingdom of God,” Ensign, May 1995).