Bill Marriott puts faith at the forefront of his life, and that's no secret. In the rooms in his hotels guests can find a copy of the Book of Mormon and Bible. At a party celebrating the opening of his $24-million Los Angeles hotel Bill recalled a memorable moment with John Wayne: “He was a very large man and a man of few words, but he let me know exactly what he wanted—a drink—when he said, ‘I understand liquor flows like glue at Mormon parties.’” There was little doubt in any one's mind that to Bill Marriott, faith and family came first.

Staying Humble

Bill was actively involved in rearing his own children. Being one of the wealthier families in America created the risk of those children being spoiled, so Bill and Donna wanted to do all they could to prevent that. “My parents had the philosophy that we only spend money on education and travel,” Debbie said. “We didn’t grow up with fancy cars or a big house.” The only exception was that each of the children got a car when he or she turned 16. Bill explained, “That was about the only thing we indulged in, but it was probably because we didn’t have to drive the kids around then.”

If the Marriott children wanted money, they could work for it. . . .

Humility was one of the greatest lessons Bill and Donna felt they could convey to their children. By their behavior over the decades, no one could accuse them of showboating at public functions or acting as if they deserved the spotlight. Bill felt strongly that the family wealth threatened to make his children prideful if he and Donna did not pass on their own natural self-effacement. “We used to say, ‘There are no big shots in this family.’ And that’s the way we’ve operated,” Bill said.

The lesson worked, even during the teenage years, when adolescence tends to induce a sense of entitlement. In 1970, Washington Post magazine writer John Carmody joined Bill and his family for several weeks of close observation. He concluded in his comprehensive profile: “Bill Marriott has a family that looks as if it had just marched out of a life insurance commercial. . . . Their church is an integral part of their lives: they truly do pray together and play together. When they are out in public the boys shake hands solemnly with the grownups and they all, mom and dad and the kids, fall into a laughing, easy comradeship that makes the people at the next table, or wherever, look and smile back without quite knowing why. It is, in sum, one of those families a great many people in the United States still hope to have.” . . .

In spite of his career demands, Bill put his Christian faith first, which included serving in a succession of ecclesiastical positions in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. . . . Bill became a high councilor in the Washington D.C. Stake in 1974.

The most rewarding high council assignment for Bill was his role in the opening of the Washington D.C. Temple in 1974, a building for which his father had lobbied over the years. The massive, six-spired edifice covered with white Alabama marble was showcased for the public during an open house in September and October. A total of 758,322 visitors toured the temple. Bill was tasked with hosting a day for business VIPs. They began their tour with breakfast at the Key Bridge Marriott, where Bill had salted the crowd with Latter-day Saint executives from the company among the tables to answer questions about the Church. In conjunction with the open house, Allie, a Kennedy Center board member, arranged for a September concert by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir at the Center, which was attended by newly inaugurated President Gerald Ford and the First Lady.

More often than not, Church work for Latter-day Saints, even famous ones, is anonymous or behind the scenes. Few in the Church in high or low positions escape the thankless task of setting up or taking down chairs for church meetings or cleaning the buildings. Bill was not above that duty. On the Saturday before the D.C. temple dedication services, Allie reported that Bill was exhausted from carrying chairs up six flights of stairs in the temple for two hours. “It made him sick, since he was still weak from the stomach flu he just got over.”

A New Calling

Life-altering personal events in the summer of 1975 competed for Bill’s attention. Debbie graduated from high school and went off to Brigham Young University, and the family became fully aware of Stephen’s multiple health issues. When Stephen was about twelve years old, he began to lose his hearing, but it was a couple of years before either he or his family realized it. His parents had gotten used to Stephen’s “What’d you say?” during conversations. A few days after Debbie’s graduation, Donna felt prompted to ask Stephen, “Are you not hearing me or just not listening?” Stephen thought about it for a moment, and then he said that maybe he couldn’t hear as well as other people. He was soon diagnosed with a severe and potentially degenerative hearing loss. “My dad put his arms around me, and he sometimes cried with me. He also spent all day waiting with me at hospitals.”

In the same month as Debbie graduated and Stephen was diagnosed, Bill received a significant change in his Church assignment, to become bishop of his ward—the equivalent of a pastor. He reluctantly agreed to what essentially amounted to a full-time volunteer job. The day before the news was announced to the Chevy Chase Ward, [Bill's father] J.W. did something almost unheard of in the Church. He called the President of the Church to ask that Bill’s assignment be rescinded. He knew President Spencer W. Kimball would give him a respectful hearing because they were friends. Kimball took J.W.’s phone call and listened as J.W. said Bill was simply too busy at Marriott to be a bishop on the side. “This calling was approved by our First Presidency, and we’re not going to reverse it,” Kimball replied.

A key reason for Bill’s unhesitating acceptance of this new call was his admiration and respect for the man who had issued it, President Kimball. . . . The Marriott family knew Kimball to have a spirit far stronger than his body. He had stayed at the Marriott home in 1957 on his way to New York for an operation for his throat cancer, and he had greatly impressed Bill and J.W. with his insistence on performing extensive duties in spite of his illness.

“If someone were to ask me who was the most powerful and influential man in the world today, it would be President Kimball,” Bill unabashedly pronounced during the Latter-day Saint prophet’s life. “He is the most dynamic leader of the Church in this century. But to me, his greatness is in compassion and humility. He has said his life is like his shoes: to be worn out in service. He has been an example of complete submissiveness to the will of the Lord, of meekness and love.”

For President Kimball’s part, Bill’s acceptance of the call to serve as bishop increased the prophet’s fondness for his friend’s son. In letters to J.W., President Kimball often inquired after Bishop Marriott, calling him “delightful,” “excellent,” and “a credit to the Marriott name.” In one of the sweetest moments in Donna’s memory, after a standing-room-only regional meeting at the new Washington D.C. Stake Center, President Kimball took the time to stop and give two-year-old David a kiss on the cheek. . . .

An Act of Faith

Bill’s ready acceptance of the call to service might have been the greatest act of faith he had ever shown. He felt ill-prepared and thought the timing couldn’t be worse. As the CEO of a $732-million company in the middle of a recession, his plate was already full. He coped by delegating and organizing and by using his business skills at church to make sure the trains ran on time.

He found himself in charge of a large contingent of Hispanic Latter-day Saints who were absorbed into the heavily Anglo Chevy Chase Ward when their own congregation was disbanded. The Hispanic members felt they had lost their footing, so Bill created a “translation booth,” from which English-to-Spanish translations of sermons were transmitted via headphones to the Spanish speakers seated in nearby pews. When one of them spoke from the pulpit, a simultaneous translation into English was piped into the chapel.

The work of a Latter-day Saint bishop is partly administrative but also heavily weighted with one-on-one care for congregants and pitching in alongside everyone else. True to the family motto, Bill’s “no-big-shots” behavior impressed everyone. He was often one of the last to leave after a ward social event, and, with his family, he could be found in the church kitchen doing dishes and mopping the floors. . . .

Bill said, “Some of the happiest moments I ever had as a bishop were when a member came to me and said, ‘I want to come back. I’ve been outside the Church for many years and I have not found happiness. I know that the other way is not good. I want to return to the gospel.’ What a great thrill and blessing it was to bring back just one member to that joy.”

As a bishop, Bill presided over Sunday worship services, performed marriages, conducted funerals, attended ward socials, and went on ward campouts. It was, perhaps, the latter that was the greatest challenge. He hated camping and would outfit a full bed in the back of his station wagon to avoid sleeping in a tent. David Fell, who was the ward executive secretary for Bishop Marriott, recalled that Bill would also don a sleeping mask that made him look like the Lone Ranger. “That’s how he survived the campouts. But he came, and that spoke volumes.” . . .

Perhaps only in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints could a Fortune 500 CEO counsel with a Church member about a deeply personal issue one day and then report to work the next morning and make multimillion-dollar decisions. “As bishop, I was dealing with every kind of thing imaginable—marital problems, kids on drugs, people in abject poverty who couldn’t get jobs,” Bill recalled. At first, he wore himself out in the effort. “It took about six months before he realized there was no way he could solve all those problems. He wasn’t a trained psychologist. He was just one man. He decided he could do no more than to do the best he could and pray that would suffice,” Donna said. . . .

Looking back on Bill’s time as bishop, Donna considered it nothing short of miraculous that her husband could fit it all in. “When he became bishop, I didn’t know where he would find the extra time he needed to do it,” she said, “but the Lord blessed him to carry out his calling. We had a wonderful spirit in our home. He was able to do what needed to be done as bishop, still keep up with his job, and always be at home when he was needed.” Blessings aside, though, the time-consuming calling could not help but sap some of his energy. “He had very, very long Sundays,” Donna recalled. “First there were the church meetings, and then he’d stay after church to counsel with people in his church office. After that, he’d make hospital visits or go to the members’ homes to talk with them. Then he’d go to work Monday morning just wrung out. People couldn’t understand why he was so tired on Monday. They’d all been out playing golf.” . . .

In May 1977, after two years in his Church calling, Bill was released as bishop to take an assignment as the first counselor in a new Washington D.C. Stake presidency. After the reception honoring Bill as the outgoing bishop, Allie recorded with exultation: “All said Billy was the best Bishop they had ever had.” It had been a time when Bill said “the need to rely on the Lord became very important to me.”

Longtime friend Jon Huntsman observed a few years after his friend’s release as bishop that “the happiest I’ve ever seen Bill was when he was bishop—when he was literally working around the clock with families who didn’t have anything. He seemed to thrive in that atmosphere. He radiated a sense of inner peace and contentment.”

Two decades after his release as bishop, Bill reflected that the service “really brought me to a much better understanding of our associates in our company—what kind of problems they have in making ends meet, in trying to raise their families, trying to get their kids to do right, trying to provide healthcare and pay the light bill, the heat bill, the rent. When you’re the CEO of a company, it’s hard to really understand what’s going on in people’s lives that are working down in the trenches. The Church job gave me more empathy. I became a better listener because of it. Those two years became an anchor in troubled times. No question about it.”

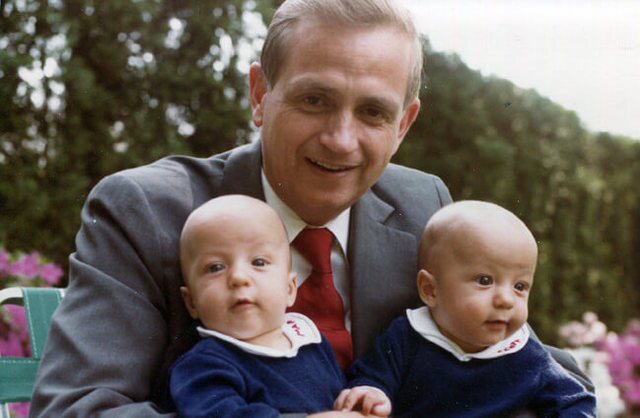

Lead image of Bill with his grandsons Mark and Scott. Photo by Gale Frank-Adise.

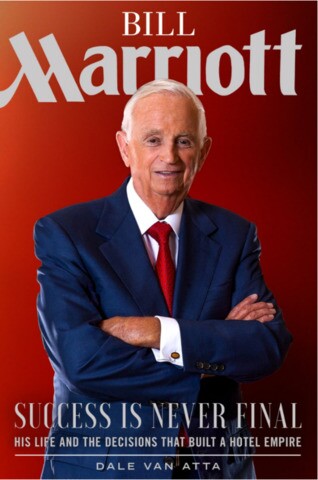

Read more about Bill Marriott's life in Bill Marriott: Success Is Never Final—His Life and the Decisions That Built a Hotel Empire.

Bill Marriott, son of J. Williard Marriott who opened a root-beer stand that grew into the Hot Shoppes Restaurant chain and evolved into the Marriott hotel company, grew up in the family business. In his more than fifty years at the company’s helm, Bill Marriott was the driving force behind growing Marriott into the world’s largest global hotel chain.

Bill Marriott: Success Is Never Finalgives readers an intimate portrait of the life of this business titan and his definition of success. Bill shares details about his private struggles with his father's chronic harsh criticism; his innovations in the hotel industry; and the boundless passion and energy he demonstrated for his work, family, and faith. Bill also shares spiritual experiences that allowed him to recognize God's guidance in his personal life.

This fascinating biography tells the story from Bill Marriott's first job in his family's restaurants to his monumental decisions in building a hotel empire. It is the remarkable story of a man who had the vision to create a multi-billion-dollar business, who understands the power of giving through substantial philanthropic work, and who lives the creed that hard work will pay off but success is never final.