Though born in Jerusalem a short distance from where the Savior—already whipped, bruised, and tortured—was executed on a cross, Sahar Qumsiyeh grew up in Bethlehem—the land of Jesus Christ's birth. But the sunbaked streets that Qumsiyeh knew held little reminiscence of biblical starlit skies and angelic choirs.

Instead, Qumsiyeh remembers the echo of bullets, the sting of teargas, and fear. In fifth grade, Qumsiyeh recalls, she heard the familiar sharp clang of rubber bullets outside as soldiers opened fire on children demonstrating at her school. A tear gas bomb rolled into her classroom as a fellow classmate curled up screaming. “We all wanted to go home and be in the safe arms of our mothers—but that was not permitted until the shooting stopped,” Qumsiyeh writes in her memoir, Peace for a Palestinian. Hours after that confrontation, a petrified Qumsiyeh walked home past the same soldiers who had fired at her schoolmates. But they did not shoot.

It would be several years later, when Qumsiyeh was 14, that an Israeli would first shoot at her.

Praying for Death

While playing with her cousins in the street, Qumsiyeh saw an Israeli settler stop her car before opening fire. “I don’t know if somebody threw a rock at her car or what, but she felt threatened,” Qumsiyeh says. “She got out of her car and started shooting in all directions. I remember hiding behind a fence and shivering because the gunshots were so loud. I felt they were going to come through the fence and kill me.”

The violence—fueled by decades of killing, animosity, and unrest—reached a new peak as Qumsiyeh graduated high school and began attending Bethlehem University in 1987, the year the “Stone Uprisings” began. Palestinian men and boys would blockade streets, set car tires on fire, and throw stones at approaching soldiers.

“At the time, . . . I was not interested in politics, so I kept myself distant from these demonstrations. However, what happened on October 29, 1987, changed all that,” Qumsiyeh writes. Late that morning, protesting students gathered for a demonstration on campus. When Israeli soldiers arrived, some of the students hurled rocks over the university’s 10-foot wall. Clouds of tear gas filled the campus, and the wall, once a shield protecting students from direct clashes with the guards, now became a prison.

Qumsiyeh huddled in the science building, catching stinging whiffs of the suffocating gas and watching injured students being dragged to the university’s small medical clinic. “At first their injuries were related to the tear gas,” Qumsiyeh remembers. “Some had passed out, and others were very dizzy. But then we noted students with bullet wounds being admitted.”

Among the wounded was a young Palestinian named Isaac, whose limp body was carried by four students, each bearing a limb; blood was dripping from a bullet wound in his head. “Isaac had been on the roof of the cafeteria hanging a Palestinian flag when an Israeli soldier shot him,” Qumsiyeh writes. “We expected Isaac to be rushed to a hospital. But . . . the soldiers would not allow him or anyone else to leave the campus. We sat there for two hours as Isaac fought for his life. Everyone was silent. Suddenly nothing else mattered. Isaac was slowly dying.”

Then something penetrated the silence. “I remember everyone singing patriotic songs, and it did something to me. It changed something inside me,” Qumsiyeh says. Late in the day, Isaac’s body was allowed to be taken to the hospital, where his organs were transplanted into Israeli patients. “At midnight, soldiers brought Isaac’s lifeless and empty body to his home in the Aida Refugee Camp and allowed only his parents to accompany their transport of the body to a remote field far from Bethlehem,” Qumsiyeh writes. “[They] dug a hole and threw Isaac’s body inside and then covered the hole with rocks and dirt.”

After Isaac’s death, the Israeli military closed Bethlehem University, but Qumsiyeh began attending demonstrations, refusing to use violence but also refusing to let others be slaughtered without acknowledgment. Qumsiyeh walked in protest after Anton, another of her classmates, was stopped by two Israeli border policemen who shoved an automatic weapon into his back and fired three times at point-blank range. They then dragged him down a flight of stone steps to conceal his body while he bled to death.

Demonstration in Beit Sahour after a Palestinian was killed in 2000.

“In Israeli law, basically you could kill a Palestinian, you could put a Palestinian in jail, you could beat up a Palestinian—there’s nothing, [no punishment]. Nobody really cares,” Qumsiyeh says. “I started to wonder if Palestinian lives were as important as other people’s lives. . . . All these things I saw made me hate the soldiers.”

With businesses and schools closed because of strict militaryenforced curfews, Qumsiyeh had ample time to dwell on her hatred—on the hopelessness, injustice, and devastation of watching homes demolished, family members imprisoned without explanation, and her nation’s flag torn down and burned.

“I wondered why God had abandoned me and my people,” Qumsiyeh writes. “I felt my heart fill with the darkness of anger and hate. I longed to die. In fact, during some demonstrations, everyone else ran from the Israeli soldiers while I stood still. . . . I saw no hope in the future; I began to pray to Heavenly Father, asking Him to end my life. One day I prayed with such intensity and faith that I thought He must have heard me.” Qumsiyeh reached the end of that day with her mind, heart, and pain as alive as ever. “I knew there was a God,” she says, “and I knew He listened. [But] because I prayed so much for Him to end my life, and He didn’t answer, . . . I [thought], ‘Well, He doesn’t care.’”

A Flicker of Light

After Bethlehem University reopened, Qumsiyeh received her bachelor’s degree in mathematics in 1993 and quickly determined she wanted a master’s degree—an impossibility in Palestine at the time. After applying for scholarships across the United States, Qumsiyeh received a dream scholarship of $56,000 to American University in Washington, D.C.

But then she received a call from Brigham Young University, to which she had applied on a whim after spotting an advertisement in a local newspaper. Qumsiyeh knew little about BYU except that it was located in a desert her family told her was inhabited by religious zealots who did not drink tea, coffee, or alcohol. Virtually everything Qumsiyeh read or heard about Utah seemed alien and unappealing, which should have made it easy to turn down the $10,000 scholarship offer.

Yet she agonized over her choice. “I lit a candle in the Church of the Nativity . . . and I said a prayer,” Qumsiyeh says. Raised a Christian, Qumsiyeh knew rote prayers, but the only times she had prayed expectantly and sincerely were when she begged God to take her life. “After this particular prayer, however,” she says, “I had a strong feeling in my heart—a feeling I could not deny—saying that I should go to BYU.”

Despite this conviction, she waited for a divine voice, a grand revelation, or the heavens to part, but God provided no manifestations or heavenly signs. In the end, Qumsiyeh defied her family’s wishes and followed the subtle prompting by attending BYU in 1994.

“From the little I knew about [Latter-day Saints], I figured it would be hard to get used to being around them,” Qumsiyeh recalls. “The strange thing was that from the moment I arrived on BYU’s campus, I felt loved and welcome. . . . I had never seen people treat me that way and respect me the way people did at BYU.”

Despite this embrace of love and kindness, Qumsiyeh felt that the dreams and fears inescapable to her seemed alien to or ignored by those who surrounded her. “Few of my new friends seemed remotely capable of understanding how difficult my life in Palestine was,” she writes.

Qumsiyeh never felt more foreign than when attending church with her Latter-day Saint friends. But the promise of hearing a living prophet encouraged her to listen to general conference that fall.

“During conference, when my friends said the prophet was going to speak, I was curious,” Qumsiyeh says. “One of the speakers referred to my land as Palestine, and that meant something to me. . . . It felt like somebody was acknowledging my identity and my right.” Qumsiyeh suddenly felt noticed and acknowledged, and she knew that “a church that did not hate Palestinians must be a good church.”

Her head still ringing with conference messages, Qumsiyeh asked her friend Shae about the Church. Shae began by speaking of the premortal world, explaining the creation, our divine nature and potential, the Atonement of Jesus Christ, mortality, suffering, and life after death. “Others in the room objected to Shae’s approach because they thought she was telling me too much and would confuse me,” Qumsiyeh remembers. “But to me it was as though Shae were putting all the pieces of a puzzle together, and for the first time I could finally see the beautiful picture—a picture that was so clear and cohesive.”

Qumsiyeh received a copy of the Book of Mormon in Arabic, and she began relishing opportunities to attend church. She writes, “I learned to love the Church more and more with each visit. Everything that was taught sounded so logical and perfect to my ears and my heart.”

After she finished reading the Book of Mormon in 1995, an unshakable peace enveloped Qumsiyeh. She says, “I just remember that good feeling of peace that I [had] found the truth. I just knew it. I finished reading the Book of Mormon—I never needed to kneel down. I never needed to ask because . . . I already knew the answer deep in my heart and with every fiber of my being.”

However, knowing the truth and becoming a member of the Church were two separate crossroads for Qumsiyeh. By committing to baptism, Qumsiyeh risked ostracism and persecution by her people and the heartbreak and antagonism of her family. But when Qumsiyeh’s friend asked her, “Sahar, are you willing to follow Christ and be baptized?” her one-word reply changed her life: “Yes.”

Sahar Qumsiyeh on her baptismal day. She became baptized a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints while attending BYU.

On February 4, 1996, with 160 friends gathered to support her, Sahar Qumsiyeh was baptized a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. “As I came out of the water, I knew that I was born again,” Qumsiyeh writes. At that moment, she understood that Heavenly Father loved her, heard her, and had indeed answered her most desperate prayer: “Heavenly Father did end my life—He ended my life of misery, despair, and pain and gave me a new life of light, peace, and happiness.”

The Depth of Faith

Five months after rising from those baptismal waters, Qumsiyeh returned to Palestine, where family members berated her with controversial teachings and hateful comments about the Church. Their mocking was like a firehose on her flickering testimony. Her mother threatened to burn Qumsiyeh’s scriptures, telling her she would never marry. She had become a pariah and brought shame to her family, and in a region limited by travel restrictions and economic turmoil—where family meant not only belonging but survival—Qumsiyeh felt more isolated than ever.

Just before Christmas 1996, Qumsiyeh reached her breaking point. All day long, her brother bombarded her with vilifying messages, even continuing without interruption as Qumsiyeh curled up in her bed to sleep. Broken and overwhelmed, she rushed to the bathroom to find a moment of respite. “[At that point,] I didn’t have faith anymore. I didn’t even believe that God existed. I just lost everything,” Qumsiyeh remembers. Kneeling on the cramped bathroom floor, she “gathered the little bit of faith” she still possessed and asked, “Heavenly Father, are you really there?”

Later that night, Qumsiyeh experienced a divine manifestation too sacred to share, one that assured her of God’s soul-shaping peace and love. “I never doubted again,” she says. “I knew He was there. I knew He existed. I knew He cared.”

Sahar Qumsiyeh with her family in Palestine.

That reassurance strengthened Qumsiyeh as she risked imprisonment by breaching political divides to worship at the nearest Latter-day Saint meetinghouse in Jerusalem. Only five miles separated Qumsiyeh from the city of her birth—five miles littered with soldier-controlled checkpoints, barbed wire, concrete walls, and decades of death and hostility.

Palestinians were required to obtain permits to travel anywhere outside the Israeli-occupied West Bank, and obtaining a permit to enter Jerusalem was nearly impossible. Qumsiyeh had a choice: she could allow herself to become estranged from the Church— forfeiting her greatest source of peace—or she could risk imprisonment and death by illegally sneaking into the City of Peace.

“I knew God’s laws were above any of man’s laws,” Qumsiyeh writes. “For me, making that arduous and risky weekly trip into Jerusalem was more than an act of obedience. It was something I did because I felt my soul would simply die spiritually without it.”

Sahar Qumsiyeh at the Israeli-Palestinian border. After waiting for hours at the border, Qumsiyeh would often be turned away, forcing her to risk her life sneaking into Jerusalem to attend church.

Every Sunday for 12 years, Qumsiyeh traveled for hours along rutted backroads, climbed through jagged holes in walls topped with razor wire, skirted past armed soldiers, scaled 10-foot concrete barriers, and hid from the police in backyards and alleyways.

“I often felt Heavenly Father’s hands carrying me to and from church. I was shot at once when the soldiers discovered me climbing a hill trying to sneak into Jerusalem. I was attacked twice by men who tried to rape me as I was alone on those hills,” Qumsiyeh recalls. “I honestly look back and say I would have never made it without Heavenly Father’s help.”

With each passing frustration or terrifying encounter, Qumsiyeh’s faith broadened. Each week as she pressed the sacrament bread to her lips and felt the water moisten her tongue—remembering the Savior’s torn flesh and free-flowing, freely given blood spilt less than five miles from where she sat—she better understood His sacrifice and His Atonement.

The Savior’s grace and Qumsiyeh’s faith allowed her to witness miracles. One Sunday, when a strict curfew was placed on Bethlehem residents after a Palestinian had been killed, Qumsiyeh braved stepping outside her front door. She knew Palestinians who had been shot for such an offense, but she also knew she had been assigned to give a talk that day in sacrament meeting. “I decided that I could only step outside. That was all that I could do,” Qumsiyeh writes. “I had faith that Heavenly Father, somehow, would do the rest.”

After stepping from her front porch into the street, Qumsiyeh heard a car approaching. A taxi driver had taken the obscure side street near her house to avoid soldiers. The driver stopped and, telling Qumsiyeh he was heading to Jerusalem, offered her a ride. Though they had to drive through an abandoned field to enter the Holy City, Qumsiyeh knew the Lord had provided a way.

Peace and Perseverance

Qumsiyeh continued undaunted in her faith. In 1997, a friend purchased a plane ticket for Qumsiyeh to travel to Utah to receive her endowment, but the night before she was to leave, a bombing in Jerusalem caused Israeli authorities to refuse travel to any Palestinians. With the proper permits already in place, Qumsiyeh hoped the restriction would not include airline flights. With the help of friends, prayer, and pleading, Qumsiyeh made it past the Bethlehem checkpoint, only to be turned back by airport security. Devastated, Qumsiyeh questioned why the Lord would allow this to happen when she was striving to enter His house. She writes:

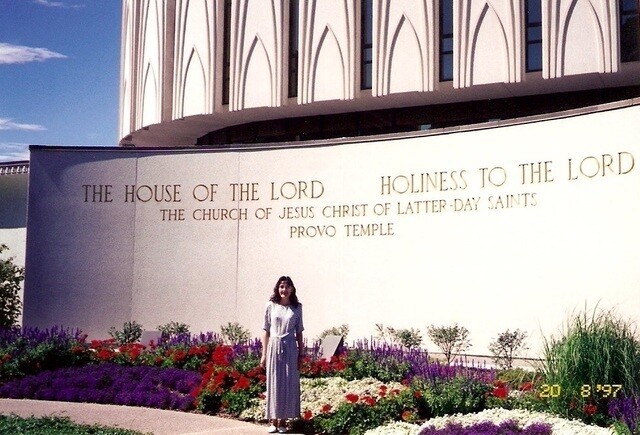

As much as I wanted to go to the temple that day, Heavenly Father knew I was not quite ready. We often think that strong faith means that we will be able to get what we need or want if we pray for it. . . . [But] sometimes God requires us to wait for the miracles and does not grant them right away, or even at all. For me, the wait made the experience of going to the temple all the sweeter. When I finally entered the Provo Utah Temple, two weeks after that hard experience at the airport, I felt that I had found the one place on earth that I belonged. Everyone was dressed in white, and I felt welcomed. In the temple it did not matter that the color of my skin was different or that I spoke a different language or that I was Palestinian. I was in the Lord’s house, and I was His daughter. It was peaceful, quiet, and safe.

Sahar Qumsiyeh on the day she received her endowment at the Provo Utah Temple.

In 2008, Qumsiyeh received what she believed to be an answer to 12 years of continual prayer—the United Nations offered her a job that included a permit to enter Jerusalem. Because of her new permit, Qumsiyeh could now regularly attend church, and she was soon called as the Relief Society president. While her new calling allowed Qumsiyeh to connect with the members in Jerusalem, it also made her aware of other members in Bethlehem who had been unable to attend worship services—some for more than a decade—because of travel restrictions.

“The walls and restrictions were not going to be removed anytime soon, so we needed a more practical solution,” Qumsiyeh recalls. “The only viable answer to assist and strengthen them became clear: we would bring the Church to them.” What began as a simple sacrament meeting in the home of one of the members in 2010 evolved into the establishment of a branch in Bethlehem in 2014. “It was great to see hope and faith come back to their lives,” Qumsiyeh recalls. “I thought getting that permit to enter Jerusalem in 2008 was the answer to my prayer, but it was only a small part of it. The Lord had something bigger and more wonderful in mind for me.”

Elder Ronald A. Rasband, then of the Seventy, visiting the Bethlehem Branch.

"Love Your Enemies"

In a land where angels proclaimed joy, peace, and goodwill on a night luminous with starlight, Sahar Qumsiyeh witnessed perpetual fear, violence, and hatred.

On a Sabbath reminiscent of the hundreds of others she had endured, Qumsiyeh recalls coming face to face with an Israeli soldier who barred her from entering Jerusalem and from the solace of the sacrament:

“Go home! You can’t enter Jerusalem! Go back!” the soldier at the checkpoint screamed at me. This soldier who had invaded my country was now telling me that I was denied access to the city of my birth. I tried to form angry words to respond to his unjust act but was halted by the words of the Savior echoing in my ear: “Love your enemies.” Memories flashed through my mind of times when I had seen these soldiers demolish homes of my relatives, beat people until their bones were broken, arrest family members, and prevent me from going to church in Jerusalem and partaking of the sacrament. . . . Anger and hate filled my soul, and I thought, How could the Lord expect me to love these soldiers? After what I have seen some of the soldiers do, He could not possibly expect me to love them! The words came again, now more real to my mind: “Love your enemies.”

Like Nephi, Qumsiyeh understood that Heavenly Father would never give a commandment without providing a way. She wrestled in prayer, begging to find the love our Savior offers to all, seeking the divine compassion that allowed Him to cry out, “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34). But Qumsiyeh was disappointed. After her first prayer, she felt no love miraculously descending upon her—nor did she feel it in the months immediately following.

“My heart was so hard that it took months for Heavenly Father to mold it and soften it. Almost a year after that event, I was heading to church on a normal Sabbath,” Qumsiyeh recalls. When a soldier turned her away from the checkpoint, along with school children and families pleading to be allowed to go to the hospital, Qumsiyeh felt something inexplicable stir in her.

Now, as I looked up at the soldier’s face, I expected to find the same hate and anger that I had found [the year before]. This time, however, my heart seemed different. As I looked into the soldier’s eyes, my heart filled with love instead of hate. These feelings of love shocked me. . . . But as I looked at that soldier that day, I saw a brother of mine—a brother not only because Palestinians and Israelis are literally related by blood but also because in front of me stood a son of God, beloved of Him.

Sahar Qumsiyeh overlooking Jerusalem from the BYU Jerusalem Center.

Qumsiyeh understands this love as a gift, a grace attainable only through Jesus Christ and His Atonement. And it is because of His sacrifice Qumsiyeh knows:

You can be happy. You can find personal peace even if you’re in a difficult situation. I grew up in this country that’s in constant conflict, and I often wondered, is peace possible? . . . But I’ve come to learn that as you follow the Savior, who is the Prince of Peace, that peace is possible. I often wonder, why was the Savior born in such a troubled place? I’ve come to understand the reason He chose it is because He wants us to know that peace comes through Him and that if we follow Him we can have personal peace. We [can] be in a difficult situation, we [can] hear gunshots or be in a place of war, and we can feel that comfort, peace, and strength as long as we’re following Him. The Savior tells us, “Peace I leave with you, my peace I give unto you: not as the world giveth, give I unto you. Let not your heart be troubled, neither let it be afraid” (John 14: 27). He is the one who is able to calm seas and calm our hearts during the storms of life. If we are obedient to His commandments even when it is hard, He walks by us and even carries us, when needed, back to His mansions above.

Peace for a Palestinian: One Woman's Story of Faith Amidst War in the Holy Land

Whether your own obstacles are great or small, Sahar's message will help you discover that the true source of peace and comfort is the same for all of us.

Read more about Sahar Qumsiyeh in her book, Peace for a Palestinian, available in Deseret Book stores and on deseretbook.com.