Editor’s note: This article was originally published on LDSLiving.com in March 2018.

As Bryan Hall walked up to a group of general conference protesters one cold October morning, he never thought that he would one day become friends with the ringleader, Ruben Israel, a man he had come to hate—a man he had never even met.

For years, this Utah born-and-bred devout Latter-day Saint had seen Israel and those like him yelling at members just outside some of the most uplifting Church events: general conference, the Manti Pageant, and the Hill Cumorah Pageant, just to name a few. He thought their antics cruel, irreverent, and ignorant. He simply could not see any good in these people.

But in Ruben Israel, he found his nemesis.

“I found myself watching all sorts of YouTube videos, documenting a number of these ‘anti-Mormons’ who were allegedly persecuting us during sessions of general conference,” says Hall. “I found myself furiously focusing on one particular protester: Ruben Israel.

“Ruben encompassed every negative memory and impression I had of these protesters growing up. He was loud. He was intentionally provocative. He was extremely in-your-face. And he was adamantly ‘anti-Mormon.’”

Hall hated what he saw. He reasoned that many Latter-day Saints must also have the same negative feelings toward these people. He hated how disrespectful they were toward things that he and Latter-day Saints everywhere hold sacred. But for some reason, Hall channeled all his anger towards the man who appeared to be their leader: Ruben Israel.

“As I dwelt on this,” he says, “the anger inside me swelled to an almost unbearable level. It’s sad to relate just how deep this anger grew within me.” But Hall thought that confronting Israel about his antics would only make things worse. He tried to push the problem away, tried to ignore it. But it was no use.

Grappling with Hate

Hall says, “In conversations with other [Latter-day Saint] friends and associates, no matter how diplomatic or soft-spoken we were, or even how angry we might become, there was no getting around the fact that talking about it wasn’t uplifting. But ignoring it was just making it fester even worse. Just the act of trying to ignore it told me that it was there and that I couldn’t ignore it.”

But ignoring it was exactly what Hall thought he was supposed to do. He had seen many angry scenes of Church members and protesters yelling, and it always went south very fast. As a young boy, Hall had grown up going to the Manti Pageant with his family in the summertime. It was there that he first recognized the anger that accompanied the “discussions” that many Latter-day Saints had with the protesters. It was there that he learned perhaps ignoring it was best.

“I was just a kid observing this from a distance, as a few members of my family tried to reason with these men. I never listened to what either side was saying. I just felt the argument. I remember feeling that something was very wrong there. But as I look back now, I realize that the negative experience was coming from the fact that everyone was breaking the commandment where Jesus says that there should be no disputations among you.” He realized that it wasn’t what they were saying that mattered—it was how they were treating each other.

Suddenly, Hall remembered another young boy who also was confused by the hatred and bickering surrounding him: 14-year-old Joseph Smith. The more Hall studied the accounts of the First Vision, the more he felt some of Joseph’s confusion was over the arguing itself.

“When I was a kid and I saw those arguments going on,” Hall recalls, “it just seemed like the most un-Christlike moment I’d ever seen. And no one in that circle of discussion—regardless of their religion—was experiencing Jesus. So I can say that I do identify with Joseph Smith’s confusion of the arguing.”

After that, Hall knew that he couldn’t sweep the hatred and confusion under the rug anymore. “I wasn’t at peace with what I interpreted to be the appropriate way to handle the situation. And so I did feel that it was spiritually my responsibility to get over this.” After a while, the anger and the inability to ignore it became too much for him. At the suggestion of a friend, Hall decided to finally talk to Ruben Israel.

“The radical thought came to me that maybe I was the one in the wrong,” he says. He remembered a scripture in the Doctrine and Covenants that says, “He that forgiveth not his brother his trespasses standeth condemned before the Lord.” Hall recalls, “Suddenly on that day, it was incredibly clear to me that the greater sin lay with me.”

So just before the Saturday morning session of the October 2007 general conference, Hall approached Israel on the street. He may have been resolved to talk to him, but he was not quite prepared for what he saw—or for what happened next.

Meeting the Enemy

As Hall approached Israel on that fateful Saturday morning, he watched with interest as Israel gave his fellow protesters a pep talk and organized the day’s events. It really struck him. “It didn’t seem as crazy as I thought it was. When I saw him in person, he wasn’t as terrifying as he seemed online.”

The next thing Hall knew, he was pouring out his apology to Israel, a man he had hated for years, yet never met. “I found myself instantly saying, ‘I’ve hated you my whole life. And I’ve come to apologize and figure out why I couldn’t reconcile it in my heart. I wonder if we could just have lunch.’”

Hall was certainly taken aback by Israel’s response. “He was so cool about it,” says Hall. “He said something along the lines of, ‘Well, brother, I don’t hate you. Make no mistake; I’m concerned about your doctrine. But I don’t hate you, and neither does Jesus.’ And in seconds, we were off and running. It was wildly different than anything I thought it would be, or anything I’d ever heard anyone else warn that it would be.”

As surprised as Hall was, Israel wasn’t surprised at all. To him, Hall was just another Latter-day Saint trying to understand why he and his friends were there. What surprised Israel was hearing a heartfelt apology from a man he had never even met.

As Hall and his friends sat around a table in a diner with Israel and his friends in downtown Salt Lake City, he was amazed to find out that these “protesters,” as he previously knew them, didn’t consider themselves protesters at all. They called themselves “street preachers.” It struck Hall that they seemed to be just as dedicated to sharing their view of the gospel as any Latter-day Saint missionary might be.

Israel talked openly and honestly with Hall about why they do what they do—and why they do it so loudly. “Everything that he thought about us was a little bit different,” says Israel. “What he saw on the sidewalk versus who we were at lunch was different than he expected. And that’s what took him a little bit by surprise.”

Hall learned that Israel lives in Los Angeles and travels all over the States to preach at various religious conventions. Once Hall realized that Israel didn’t especially hate Latter-day Saints and didn’t specifically oppose only Latter-day Saint doctrine, his perception of them began to change.

Finding a New Point of View

“You realize that their life’s mission isn’t to spread anti-Mormon propaganda,” Hall says. Their life’s mission is to teach the word of God as they see it from the Bible. That was news to him.

“It’s not just Mormons,” says Israel. “We’re outside the Muslims’ gatherings and the Jehovah’s Witnesses’, and the Catholics’. What we’re trying to do is just remind people not to outgrow the God of the Bible.”

“It had never ever once occurred to me that they could be sincere followers of Christ trying to help me,” says Hall.

And so after a very pleasant lunch together, Israel invited Hall and a few of his friends to come to dinner with him and his fellow street preachers that night after the general priesthood session. As is customary in the Latter-day Saint culture, Hall decided to bring something to dinner as a contribution and as an act of friendship—cookies and drinks would have to do.

Hall was a bit nervous as he walked up the driveway and knocked on the door. “I thought to myself, street preachers. Whoa. But they were also just people, just like me. They were praying, and they were all so thankful for the food that had been provided.” He was astounded at how grateful they were to the Lord and how gracious they were to him.

From Israel’s perspective, Hall seemed to be genuinely interested in making a connection with him and his friends. He was also very impressed that Hall had the guts to even come to dinner with a group of street preachers who looked a little rough around the edges.

“For Bryan to come to dinner took a lot of faith,” says Israel. “We could have spiked his food; we could have given him something bad to drink; we could have had guys waiting in the closet with clubs and knives and who knows what. But he went there. It took courage, and I appreciate that.”

As the evening evolved, so did Hall’s perception of these people he had once viewed as the enemy. They had come from all over the States to be there at that one gathering in order to preach the word of God according to how they felt it should be preached. And they were doing it all on their own dime.

“That’s where everything changed,” Hall says. “It was surreal because it was as if I was eating with the enemy. But they weren’t the enemy anymore. To my utter astonishment, I didn’t just find closure that night, I found a friend. Like that impossible moment in middle school when your archenemy suddenly becomes cool, something happened that would be spiritually irresponsible for me to deny. I felt the love of God for this man, and I can only give credit to the grace of Christ.”

Agreeing Not to Disagree

Neither of these men expected to form a lasting bond that night, but that’s exactly what happened. With the passing years, they continue to stay in touch. When Israel comes to Utah for general conference, Hall opens his home to him and lets him stay free of charge.

“Over the years of going to Salt Lake City, I’ve stayed at Bryan’s home,” Israel says, “even though he knows I get up in the morning, and I’m going to be out in front of the Conference Center preaching against his church. Even after conference, we’ll go to their house, and we’re up until one o’clock in the morning talking about the Bible and scriptures.”

All those late night discussions have taught them that they have a lot in common—more than they ever thought they would. And those commonalities have led them to have a sincere respect for one another.

“First of all,” says Israel, “we both like the King James Bible, and I think that’s unique. I believe that the Mormons have a lot of things that I think Christians lack. I think Mormons are very strong on family; I think they’re very strong on patriotism; I think they’re very strong on living holy.”

But even when they might disagree over the doctrine, they’re able to value the satisfaction of being friends over the satisfaction of being right.

“Because I disagree with Bryan doesn’t make him a neighbor that I can’t spend some time with,” says Israel. “I know that he’s still a Mormon, and I’m not going to change him. And he’s not going to change me. But we do actually get along.”

“I disagree with Ruben in doctrine and in method,” says Hall. But despite that, he has come to admire Israel for how dedicated he is to what he believes, even if he doesn’t approve of Israel’s methods. But even that hasn’t kept him from learning from his former nemesis.

Learning from Each Other

“I know this sounds crazy,” Hall says, “but I’ve definitely learned how to improve my own faith by listening to his little sermons. He’s a walking database of great little one-liners and sermons. And he’s got this faith that is just really crazy, genuine faith.”

Hall never expected to find that he and Israel both have an enormous amount of respect for Joseph Smith and all that he did for the early Saints. “Ruben has this reverence for Joseph Smith,” he says. That was one commonality that definitely took Hall by surprise.

“Do I agree with Joseph Smith?” asks Israel. “No. But you know what? He actually went to jail for what he believed in.” Israel may not agree with the doctrine that the Prophet Joseph taught, but he does admire the fact that he was ready to take a bullet for what he believed.

The two men talk about more than just religion, though. Israel, a California native, happens to be a huge fan of the Lakers, a team that Hall can’t stand. Needless to say, they never tire of teasing each other over the rivalry.

“We’ve had some throw downs in sports for sure,” says Hall, “since I’m much more anti-Lakers than I am pro-Jazz.”

“I know where he stands on religion,” says Israel, “so it’s not like we’re going to go after each other all day long on that stuff. Sometimes I’ll send him an email about the Lakers beating the Jazz, and he’ll respond with something in kind. And so we do kid around a little bit. He does have a sense of humor, and I—believe it or not— do have a sense of humor myself.”

Strangely enough, these two always have a great time whenever they get together. Hall never would have thought that one day he would be laughing and joking around with the man who once inspired such anger within him. And all it took was one courageous act of brotherly kindness.

“I have absolutely no bad feelings towards these people anymore,” he says. “I no longer refer to them as ‘anti-Mormons.’ They are street preachers who spend their time and money traveling the country trying to share their version of the gospel. I disagree with the approach and would argue against its effectiveness, but I admire their dedication and courage.”

Hall feels as if he finally understands what Christ meant when He said, “Love your enemies.” It was a long journey, and definitely not an easy one, but he’s realized that once you come to love your enemy, that person isn’t your enemy anymore.

“Once you experience genuine love for someone who is not of your faith,” he says, “it ought to change your life forever.”

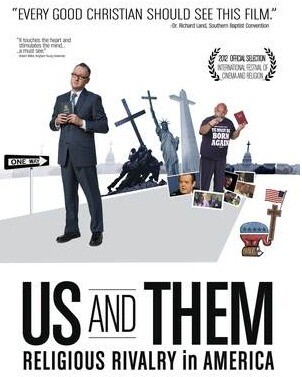

Bryan Hall shares more of his journey in his documentary Us and Them: Religious Rivalry in America. Check out the trailer below.