During my first semester as a graduate student in 1981, I read an article by Brigham Young University professor Dr. Allen E. Bergin which included a challenging statement from Dr. Albert Ellis asserting that religion had a negative effect on mental health: “Religiosity is in many ways equivalent to irrational thinking and emotional disturbance. . . . The elegant therapeutic solution to emotional problems is to be quite unreligious [as] the less religious they are, the more emotionally healthy they will be.”1

While I was initially surprised by this statement, I was also impressed by the professional and respectful manner with which Dr. Bergin responded to Dr. Ellis’s arguments. Instead of simply dismissing his fellow psychologist’s assertions, Dr. Bergin’s reply included empirical studies, philosophical arguments, and clinical evidence that I found “spiritually strengthening” and “intellectually enlarging”—two of the very purposes of a BYU education.

In the months and years that followed, I studied most everything I could find on the relationship between religion and mental health. I sensed I had found the academic, clinical, educational, and pastoral passion that would fill much of my life.2

A Controversial Issue

The relationship between religion and mental health has long been a controversial issue among mental health professionals and academics, and between religious leaders and laypeople alike. While many academics and clinicians continue to be critical of religion, there are others, past and present, who have discovered through research that religious belief and practice is a positive influence in the lives of individuals, families, and communities. William James, a physician, Harvard professor, and one considered by many as the father of American psychology, was among the first scholars to champion the positive side of this debate when in a book published in 1902 he concluded3:

We and God have business with each other; and in opening ourselves to His influence our deepest destiny is fulfilled. The universe, and those parts of it which our personal being constitutes, takes a turn genuinely for the worse or the better in proportion as each one of us fulfills or evades God’s commands.

The research I have done over the last 40 years includes studies on the mental health of many religions from the early part of the 20th century to the present. While I have sifted through thousands of anecdotal essays, media reports, blog posts, religious discourses, apologetic and polemic publications, I have spent most of my time in the academic journals and working with individuals and families in educational, clinical, and pastoral settings.

With few exceptions, my reviews of the scholarly research have produced little support for the negative assertions that religion facilitates mental illness. While the research also includes contradictions, exceptions, and ambiguities, the larger body of academic research supports the conclusion that religious belief, and most especially personal religious practice, facilitates mental health, marital cohesion, and family stability.

These positive relationships between religion and mental health are found in the research that has been done on each of the religious traditions I have studied—Catholicism, Protestantism, Islam, Judaism, and other faiths including the Seventh-day Adventist Church, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Bahá’í, and the Hare Krishna movement. Of the 540 studies that met the specific criteria for my initial study, 51 percent reported that religion was positively associated with mental health, 16 percent indicated a negative relationship, 28 percent indicated neutrality, and 5 percent yielded mixed results.4

Research on Latter-day Saints

As a Latter-day Saint, I have been pleased to discover that the research outcomes from studies on members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and mental health during the same time period reported above are remarkably positive. Nearly two-thirds of the research outcomes (71 percent) indicated a positive relationship, while 4 percent indicated a negative relationship, 24 percent indicated neutrality, and 1 percent was mixed.5 My colleagues and I are presently engaged in a review of the academic literature that will update the research on Latter-day Saints and mental health through 2021 that appears to support these same trends.6

The overall body of research from the early part of the 20th century to the present supports the conclusion that Latter-day Saints who live their lives consistent with the teachings of their faith experience greater well-being, increased marital and family stability, less delinquency, less depression, less anxiety, less suicide, and less substance abuse than those who do not.

Understanding the Grace of Christ

In addition to the positive mental health outcomes reported for those who are actively engaged in their religion, I have also observed some religious beliefs and practices that can contribute to the mental health problems that are unique to people of faith.

For example, as a mission president in the Ghana Accra Mission, I observed that some of my most faithful and fruitful missionaries were suffering from feelings of anxiety and depression. Some were even experiencing what I knew from my clinical training to be “scrupulosity,” which often includes a compulsive need to confess even the smallest of transgressions that normally would have been something they could have resolved between themselves and God.

During an interview with one of these missionaries, I observed some similarities between this young elder’s anxieties and some of the same concerns expressed by Martin Luther, the 16th-century Protestant reformer. In the following statement, Luther describes his experiences in an Augustinian monastery during his training to become a priest that paralleled the experiences of some of my struggling missionaries7:

When I was a monk, I made a great effort to live according to the requirements of the monastic rule. I made a practice of confessing and reciting all my sins, but always with prior contrition; I went to confession frequently, and I performed the assigned penances faithfully. Nevertheless, my conscience could never achieve certainty but was always in doubt and said: “You have not done this correctly. You were not contrite enough. You omitted this in your confession.” Therefore, the longer I tried to heal my uncertain, weak, and troubled conscience with human traditions, the more uncertain, weak, and troubled I continually made it. In this way, by observing human traditions, I transgressed them even more; and by following the righteousness of the monastic order, I was never able to reach it.

It has been my personal, professional, and pastoral experience that many Latter-day Saints can identify with these same feelings of anxiety and despair. Some of the missionaries I ministered to were helped by working with mental health professionals. But all were strengthened by first understanding what Luther eventually discovered about the grace of Jesus Christ and the appropriate place of good works, and then living by what they’d learned.8

Motivated by the needs I saw in people, two of my colleagues and I designed what would become the first empirical research study ever done with Latter-day Saints on the relationship between their experiences with the grace of Christ, good works, and mental health. This study was recently published in the Journal of Psychology and Spirituality.9

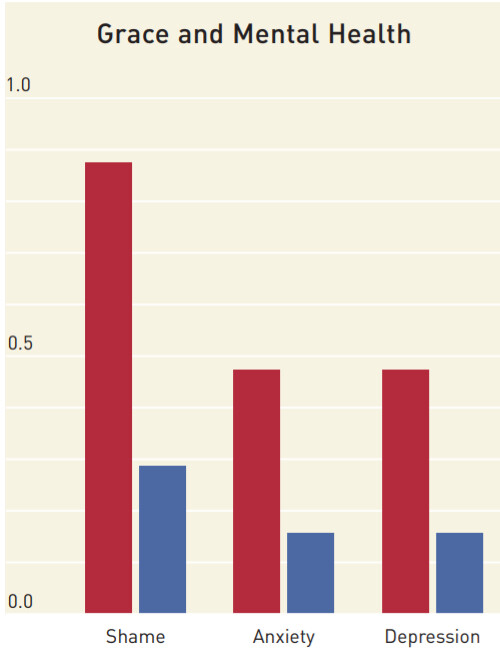

The following graph is a simplified illustration of the results:

The red bars represent the higher prevalence of shame, anxiety, and depression in the lives of the individuals we studied who focused more on their own good works (also known as legalism) rather than God’s grace. The blue bars represent those who reported less shame, anxiety, and depression because of their experiences with the grace of God.

The data from our study, collected from 635 Latter-day Saints, indicate that experiencing the grace of God has a positive relationship with mental health and that an individual’s legalistic beliefs would be correlated with decreased mental health because of the way these beliefs interfere with their ability to experience grace. Our research also supports President M. Russell Ballard’s comment that some Latter-day Saints become “so preoccupied with performing good works” that they forget the importance of having a “complete dependence on Christ.”10

Above All Else

My recently released book, Let’s Talk about Religion and Mental Health, includes many examples of the Savior’s words when he said, “For he [God] maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust” (Matthew 5:45). Faith in Christ is essential as we face afflictions of any kind, but even the most righteous and faithful among us can experience mental and emotional suffering.

I have observed that a supportive family, inspired leaders, good friends, skilled physicians, modern medicine, competent counselors, and hard work by the individuals involved all play major roles in the healing process. Above all else, the most important factors in overcoming emotional afflictions and mental disorders are discovering, renewing, and maintaining a meaningful relationship with God, following His guidance, and receiving the redemptive and enabling blessings of the Atonement of Jesus Christ. He can heal those who are “afflicted in any manner” (3 Nephi 17:9, emphasis added). I pray that each of us will one day return to our Father in Heaven having received the grace of Christ, having learned how to experience peace in this life and find eternal life in the world to come.

Available at Deseret Book and deseretbook.com.

Article Notes

1. Albert Ellis, “Psychotherapy and Atheistic Values: A Response to A. E. Bergin’s ‘Psychotherapy and Religious Values,’” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 48 (1980): 637.

2. Daniel K Judd, Religion, Mental Health, and the Latter-day Saints, (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, Religious Studies Center, 1999).

3. William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience (New York: Modern Library, 1902), 516–17.

4. Daniel K Judd (1999). “Religious Affiliation and Mental Health” (Appendix A). In D. K. Judd (editor) Religion, Mental Health, and the Latter-day Saints, Provo (Utah): Religious Studies Center (Brigham Young University), p. 257.

5. Daniel K Judd (1998). “Religiosity, Mental Health, and the Latter-day Saints: A Preliminary Review of Literature (1923–1995). In J. T. Duke (Ed.), Latter-day Saint Social Life: Social Research on the LDS Church and its Members, Provo (Utah): Religious Studies Center, pp. 473–497.

6. Daniel K Judd, W. Justin Dyer, H. G. Finlinson, and M. Gale (2021). “Religion, Mental Health, and the Latter-day Saints: Review of the Literature 2005–2021.” Manuscript in preparation.

7. Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, vol. 27: Lectures on Galatians, 1535, Chapters 5–6; 1519, Chapters 1–6, ed. J. J. Pelikan, H. C. Oswald, and H. T. Lehmann (Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1999), 13.

8. Daniel K Judd, “Clinical and Pastoral Implications of the Ministry of Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation,” Open Theology 2, no. 1 (2016): 324–37.

9. Daniel K Judd, W. Justin Dyer, and Justin B. Top, “Grace, Legalism, and Mental Health: Examining Direct and Mediating Relationships,” Journal of Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2020. Vol. 12. No. 1. 26–35.

10. M. Russell Ballard, “Building Bridges of Understanding,” Ensign, June 1998, 65.