Editor's note: This article was the cover story of the January/February 2021 issue of LDS Living magazine.

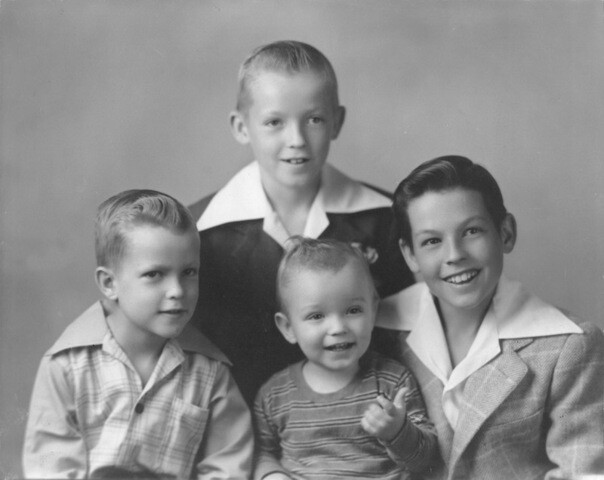

Don Bluth loved going to the movies. As a boy growing up in Payson, Utah, he would ride into the city on his trusty horse, Flash, parking him under a tree before entering the theater. While Flash “mowed the lawn,” Don experienced the magic of Disney films in all their glory, marveling at the color, music, and storytelling in each scene.

When he emerged, Don mounted Flash and rode home, passing the time by talking to his friend. The faithful horse would always respond—though whether the reply came from his own boyish imagination or not, Don couldn’t really say.

“He was very encouraging, in that he kept saying, ‘You can do anything you want to do. You just have to believe in yourself . . . and if you want to be a Disney animator and you like what that is, then that’s terrific. Go ahead and do it. You can do it,’” recalls Bluth.

Don took the advice to heart. The boy who once dreamed of being an animator would later go on to work for Disney on some of the company’s most classic films, including Sleeping Beauty (1959), 101 Dalmatians (1961), The Sword in the Stone (1963), Robin Hood (1973), Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too (1974), and Pete’s Dragon (1977, as animation director). But eventually, Bluth would be confronted with a crossroads he never anticipated, compelling him to leave the world of Disney in order to help start an independent animation firm—a move that would change his life forever.

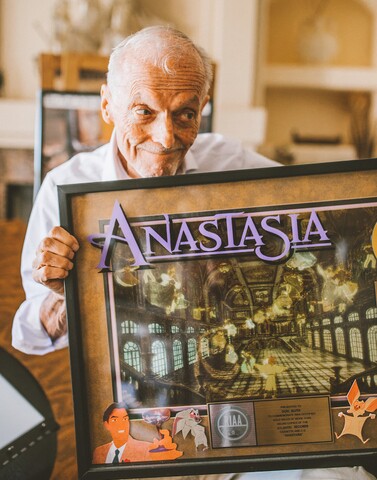

Since then, Bluth has become one of the most prestigious competitors in the industry, making his mark not only as an animator, but as a director of films like The Secret of Nimh (1982), All Dogs Go to Heaven (1989), Thumbelina (1994), Anastasia (1997), and Titan A.E. (2000). The animator has also worked with some of the biggest names in film—Bluth teamed up with Steven Spielberg in the 1980s for the much-beloved An American Tail (1986) and The Land Before Time (1988), and notable voice actors in his films include Meg Ryan, Angela Lansbury, John Cusack, Matt Damon, Bill Pullman, and Drew Barrymore.

But it’s not just Bluth’s career that is remarkable—equally significant is how his faith has shaped his life’s work.

The Crossroads

Although he spent much of his childhood milking cows on the family farm in 1944, Bluth’s heart had never really been into it. Pencil and paper were more appealing to him, and Bluth wanted to learn how to draw more than anything. But with no access to teachers or internet to search for information, he was very much on his own, learning the skill by copying the characters in Disney comic books. He practiced again and again and again—and the more he did, the better he became.

It wasn’t until around age 16 that Bluth was introduced to the world of animation by “Judge” Wetzel Whitaker, a man who had quit Disney after working on Peter Pan (1953) to take over the motion picture department at Brigham Young University.

Whitaker was an inspiration for Bluth, as it was through him that Bluth first saw the equipment purchased for BYU’s program and learned about filmmaking. It was also during this time that Bluth received a piece of advice from the BYU animation pioneer that he’s never forgotten.

“I asked him the question, ‘Why did you leave Disney?’ I couldn’t understand why anyone would, and he says, ‘It’s called a crossroads,’” recalls Bluth. “And he said, . . .‘You, sometime, will come to your own crossroads. You’ll see it,’” Bluth adds. “And I did. And I remembered what he told me.”

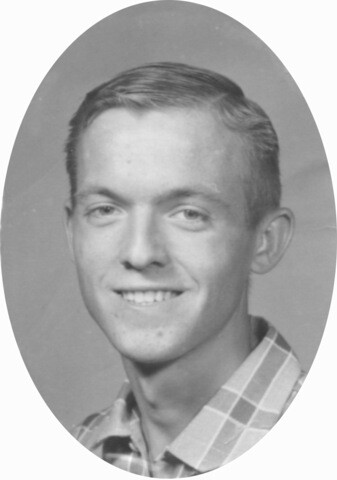

For Bluth, those crossroads would manifest in many ways. In the 1950s, around age 18, he took his portfolio to Walt Disney Productions and landed a job working on Sleeping Beauty. The film, Bluth says, was a “benchmark in the history of animation,” and Disney pulled out all the stops when they created the picture. Kelly Loosli, professor of Animation and Media Arts Fiction Production at BYU, explains that Sleeping Beauty was “more complex . . . with interesting contrast of soft forms against hard shapes, angles against curves” compared to the films before it. He adds that he can see how the movie has influenced Bluth’s work, considering that Milt Kahl—one of Disney’s core animators who worked on Prince Phillip—was one of Bluth’s mentors.

In one year, Bluth went from being a “nobody” to an assistant manager at Disney. Then his bishop called him up and asked him to serve a mission. While it meant leaving behind everything he’d worked for, Bluth prayed about the matter, counseled with his parents, and decided to serve.

“So I went to the people at Disney, and I said, ‘I’m going to go on a mission for the Church. And they were very disappointed. They said, ‘You have it all in your hands right now. You could be anything you want here at the studio.’ [They said], ‘You want to throw it all away?’ And I said, ‘It’ll come back.’”

Departing for two and a half years to Argentina, Bluth had no training program as a young elder. He bought a grammar book to teach himself Spanish, took an airplane to New York, and boarded a boat, ultimately taking a 30-day journey to get to the South American nation. To Bluth’s knowledge, he was the last Latter-day Saint missionary to depart in this manner.

During his time as a missionary, Bluth also put on two plays, The Wizard of Oz and Peter Pan, from scratch, which involved composing original music and writing the script in Spanish. It was on his mission that Bluth said gospel truths and a fresh perspective of what his future held really came together for him.

“Anything that you do with your life, you’re either a testimony of Jesus Christ or you are not. And I figured that out on the mission,” he says. “So what I did by saying, ‘Wait, this isn’t about Don and animation, this is really about my relationship with the Savior and what I can do to show love toward other people’ . . . when I finally returned and came back home, it took me a little while to get back into the animation world. But when I finally did it gave me a voice.”

Animating Again

Getting his foot in the door at Disney again “took a little bit of doing,” says Bluth. As a young man, he couldn’t settle on a major and kept “dropping out” from his studies at Brigham Young University in between working summers at Disney. Ultimately studying English, Bluth, who had never previously been a reader, fell in love with the written word. To this day, he credits the program with shaping the way he depicts characters in art.

“The drawings that I was making were no longer just drawings—they represented characters that had thoughts and philosophies. Everything kicked it up a notch. The mission did it and also the education at the English department did it,” he says.

When Bluth returned to Disney in 1971, things in the studio weren’t quite the same. According to a 1979 New York Times article, Sleeping Beauty, which took six years and $6 million to produce, was a significant factor in Disney’s loss of $1.3 million between 1959–60. Additionally, Bluth felt that public stockholders influenced company decisions, bringing the quality of production down as time-consuming special effects such as shadows, sparkles on the water, and smoke started disappearing from the company’s films.

Becoming disenchanted with the situation, Bluth resigned from Disney in 1979. But he wasn’t the only one—a number of fellow Disney animators followed Bluth to his new independent production company, including co-founders John Pomeroy and Gary Goldman.

“Some people used to ask, ‘Well, why did you leave Disney?’ because that seems like a silly thing to do,” says Bluth. “I left basically because Walt left. And if Walt wasn’t there, the vision wasn’t there. It became a mechanical process. . . . So why not make it better, when really what was driving it was bringing the cost down? . . . I mean, Michelangelo took a while to paint the Sistine Chapel. If you told him, ‘You have a month,’ what would you get?”

The Moral of the Story

A change in storytelling was another factor in Bluth’s decision to leave Disney. Believing that “a story is as strong as your villain factor,” Bluth says original Disney films like Snow White (1937), Pinocchio (1940), and Bambi (1942) taught high morals exceptionally well since the villains were so frightening. But films like Robin Hood (1973), on the other hand—which Bluth himself worked on—steered away from that tradition, opting for the comedic. Bluth felt that this made the stories more “vanilla pudding” and “soft sell” as the company became wary of upsetting viewers.

Known for often having dark themes in his own work, Bluth gravitates to a “hero’s journey” where main characters overcome difficult obstacles, believing such story lines better reflect the opposition between good and evil.

“In real life, do we have a villain? Yeah, that’s Satan. And do we have a hero? Yeah, that’s Christ. And the two are at war, and we are the booty. So it seems to me that we’re going to talk about real things—even in caricature, even in cartoons, we have to include that scenario,” he says.

Including that scenario in his own films means Bluth is also able to naturally incorporate other religious truths in his stories. In The Secret of Nimh—Bluth’s personal favorite of his films—the main character, Brisbee, has to learn how to save her son and “stop asking someone to do what you have to do for yourself,” which he feels aligns with gospel principles.

In The Land Before Time, there is also an overarching theme of families and eternal life. At the end of the movie, the protagonist, Littlefoot, believes he’s seen the shadow of his mother who died early on in the film—but in reality, it’s only his shadow on the wall.

“But when she’s dying, she does say to him, ‘I’ll be with you always.’ Now that’s a very, very [Latter-day Saint] philosophy, that the family will be together forever. . . . but I’m sure there [are] many people who are not [members of the Church] who would agree that that’s true—because it is a truth. You will be together. And life does not end when you die, or when the body has died. It continues. And the happy thought—the really, really happy thought in the gospel, of course—is that not only does it continue, but you will be resurrected.”

Perhaps Bluth cares so much about the message he portrays in his movies because of his philosophy that, as he recalls silent film actress Lillian Gish saying, each one changes you—even rearranges your very molecules—for better or for worse.

“If people realized that everything they’re going through when they sit in the dark and watch a movie, [if] they would say, ‘What’s this movie doing to me? Is it helping me, or is it making me depressed? . . . So the movie—it’s the conflict of life—the movie is either satanic or it’s godly, so which is it? And you can show villainy without being a satanic film. But some films, I know immediately, the minute I turn them on, and I start looking at it, I go, ‘I don’t want to watch this.’ And I leave it alone.”

A Conduit for Inspiration

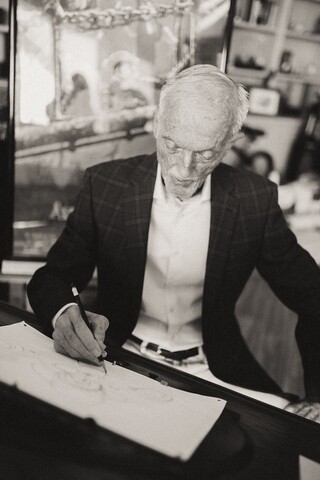

Bluth has discovered that he isn’t alone in the creative process.

“I’ve learned over the years that the ideas and the creativity are not really [mine]—that I am a conduit through which I think the Deity can talk. But it isn’t me doing it. There are moments when you feel absolutely alone and that you’re not going to be able to do it. And there are other moments when it just really flows, like water flows in a river.”

Over the years, Bluth has been involved with many parts of the filmmaking process in addition to designing characters, like orchestrating color, lighting, and story. But while he has often had to provide solutions to dilemmas in his role as director, he’s found that by staying connected to the divine, things will inevitably work out.

“There is no pressure because I think it’s all about inspiration,” he says. “You’re either the conduit or you’re not. If you try to operate on your own, you’ll fail.”

Bluth doesn’t just seek for inspiration in his work—he also seeks for revelation from the scriptures. Longtime friend Roger McKay, who has also partnered with Bluth in creating a community theater in Scottsdale, Arizona, says he’s often seen this in action.

“I’ve watched Don over the years, and he’s like a little kid sometimes when he discovers something in the scriptures, and we’ll sit down together and [he’ll say], ‘Did you know this? Did you read about this? Do you know what this means?’ And he’ll start talking about these little principles in the scriptures and just delving into them . . . he’s taught me a lot and he’s always curious like a little child. It’s amazing.”

Bluth says the scriptures, in addition to inspiration from the Holy Ghost, are key to one’s personal testimony and knowing gospel truths with certainty.

“There was a Charlie Chaplin movie, in which he is tossing the world like a big balloon. It goes up and down, and up and down, right? [He keeps] pushing it up. Testimony is much like that. Sometimes it’s very strong, sometimes it’s weak and it’s coming back down,” he says. “So the scriptures are there . . . if you don’t reach out and knock, you won’t [understand] them. And . . . the Holy Ghost is the revelator. He’ll come and he’ll give you assurances of what the truth is from the inside . . . . The Holy Ghost can prove anything.”

From serving as a branch president in Ireland when he relocated his animation studio in the 1980s to his current calling as a Sunday School teacher, Bluth will do “everything in his power” to make sure he delivers what’s needed, says McKay.

“He doesn’t want to miss out, and he wants to make sure he’s serving diligently and faithfully,” McKay says. “Even during the pandemic, he’s figuring out creative ways of teaching and making sure he doesn’t miss a Sunday or miss what he’s supposed to teach. He’s just very, very diligent. Very disciplined and dedicated.”

On and Off the Stage

Bluth is also a much beloved part of his community. Since 2004, he has worked with vice president and producer McKay by putting on plays through the Don Bluth Front Row Theatre. The theater—which for nine years presented shows from Bluth’s home living room—puts on classic plays like Fiddler on the Roof, The Sound of Music, and Hello Dolly. On performing nights, says McKay, Bluth can be found at the front door greeting patrons and listening to a story or two.

This love of theater is also reflected in Bluth’s animation. When it comes to drawing, he says, “If you can’t make your characters look like they’re emoting some kind of emotion or doing the acting process, then the animation’s not very good. Animators are really just actors, but they draw their performance instead of being onstage.”

In both his work and in caring for others, Bluth is always “looking out for the underdog,” McKay says. He’s focused on two very important things—love and a yearning for home, likely because these principles “drive his own life.”

“I think he always looks at his work, whether it be theatrical, plays, or films, through the lens of ‘How will this uplift my audience?’” he says. “He always looks through the lens of upliftment, of ‘How can I bring someone up with my work?’”

The Stories Worth Telling

A lot has changed in the animation world since Bluth, now age 83, began working at Disney as a teenager. Marketing often drives the content these days, and with the cost of movies going up, more eyes have to be on a film in order for it to be profitable. There is also more competition, with studios producing movies around the world, so it can be hard to “break through the noise,” says Loosli. So the fact that Bluth has made so many films is a feat in and of itself.

“A number of people have tried [building an independent studio], and if they were lucky, they were able to make a single film. That film may have even made a little money . . . but rarely is that person ever able to make another film again. Don defeated the odds, and through perseverance and determination made quite the collection of films over his career. I can’t think of anyone who has done what Don has. It’s pretty remarkable.”

As the animation world has shifted from hand-drawn to computer animation, Loosli says Bluth’s work will stand on its own as it’s part of the original art form that makes his films so distinct.

“Many of Don’s films will stand the test of time because they were hand-animated by true craftsmen, by people who were passionate about the stories they were telling and the medium they were telling them in. He will always be seen as one of a small handful of key people who gave new life to the animation industry,” he says.

With 11 of his own movies and one short under his belt, Bluth currently spends most of his time teaching online drawing courses at Don Bluth University, writing an autobiography, and working on Don Bluth Studios’ latest project, Bluth Fables. Based on short stories written by Bluth, which are reminiscent of nursery rhymes and Aesop fables, the project highlights the studio’s signature hand-drawn animation in short stories in motion. Recently, the Latter-day Saint also struck a deal with Netflix, which will be making a live action movie of Bluth’s video game, Dragon’s Lair (1983), in the not-too-distant future.

But in the meantime, if there are other stories left to tell, Bluth will be sure to recognize them.

“I think the only story that’s worth telling, really, is one which nudges you toward the truth, meaning the truth of life, eternal life, everything. What nudges you toward that? And finding out who you are—so many people don’t know who they are at the heart of them,” he says. “So any movie that I can make, if it can help people get there, I’d be interested in doing that.”

Art, concludes Bluth, can be “a wonderful medium if you say it right.” And if there’s one thing he hopes his work does say, it’s that it conveys one of God’s greatest commandments—to love one another.

“The most important thing, the greatest gift of all, was given by the Savior. And so I keep that in mind all the time. I can’t top anything. What He did is gave life. He gave light. He gave information. He gave joy. He gave everything that makes life worth living. So . . . the little things that I might do can underline that,” he says. “What I’m trying to [do] with art is be sure that [I] inspire people to love themselves and to be able to love other people. That’s important. And that is basically the teaching of the Savior.”