Jane Elizabeth Manning was born in Connecticut in about 1820. Her mother had been enslaved, but she was emancipated by the time Jane was born. Jane’s father died when she was a young child and, perhaps in part for that reason, Jane began working as a domestic servant for a wealthy white family in the next town over. As a young woman, she was baptized and joined the local Congregational Church, but not long afterward she heard a missionary from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints preach and she was convinced by his message. She was baptized a short time later, and she appears to have persuaded her family to join the Church as well. In 1843, the Mannings joined an interracial group of converts for the journey to Nauvoo. Although they left the Northeast together, the group was separated at some point during the journey. The white members continued to Nauvoo on public transportation; the black members walked. When Jane and her family reached Nauvoo, they were welcomed by Emma and Joseph Smith and stayed in the mansion house for a short time while they found jobs and housing. Jane remained in the mansion house, working for the Smiths as a domestic servant.

Jane probably received little material compensation beyond room and board in exchange for her labor in the Smith home, but years later she remembered her reward coming in the form of intense spiritual experiences. On her first day of work for the family, Jane recalled in her autobiography, she did the laundry. “Among the clothes I found Brother Joseph’s robes,” she said. “I looked at them and wondered. I had never seen any before, and I pondered over them and thought about them so earnestly that the Spirit made manifest to me that they pertained to the new name that is given the Saints that the world knows not of. I didn’t know when I washed them or when I put them out to dry.”1

Jane was so taken with Smith’s temple clothing that she shared it with one of the other “hired girls” who worked at the mansion house. Many years later, Maria Jane Johnston Woodward declared that she could “bear testimony that [Joseph Smith] had had his endowments and wore garments, for the woman who washed for the family showed them to me.”2 Jane would not be allowed to receive her endowment during her lifetime because Church leaders would ultimately decide that her black skin disqualified her from participating in this and other temple rituals. Telling the story of Joseph Smith’s robes at the beginning of the 20th century, Jane implicitly protested this ruling, pointing out the intimate access she had to the Church’s first prophet and to knowledge of the closely guarded temple rituals.

Jane was not the only uninitiated church member washing temple robes. In 1902, Woodward told of a time when she was working for Joseph Smith’s uncle.

“On one occasion the Prophet [Joseph Smith] wrote a letter to his uncle to meet him the next morning in Nauvoo, (we were twenty- five miles from there). Mother Smith, [his wife, Joseph’s aunt] . . . was sick and as I was the hired girl I had to get these clothes and fix them in time for Father Smith to meet the Prophet Joseph in Nauvoo. Mother Smith told Father Smith to explain to me about this clothing, what they were for and what they did with them, the reason he had to have them and have them in good condition, before I got them out, and he did so. That was the first I knew about endowment clothes.”

Woodward’s reminiscence included details about the great care with which this clothing was treated. Father Smith’s clothes “were in a chest locked up, inside of a little cotton bag made for the purpose,” Woodward recalled. “These clothes were never put out publicly, in the washing or in any other way. When we washed them we hung them out between sheets, because we were in the midst of the Gentiles.”3 Jane did not recall any special information from Emma Smith regarding Joseph’s temple robes, but, like Woodward, she may well have received some instruction in order to explain the special treatment the clothing required.

Joseph Smith’s mother, Lucy Mack Smith, afforded Jane further access to the most closely guarded aspects of the tradition. Jane recalled that “Mother Smith,” as Lucy was commonly known among the Latter-day Saint community, “would often stop me and talk to me. She told me all Brother Joseph’s troubles, and what he had suffered in publishing the Book of Mormon.” Jane was an appreciative audience for Mother Smith’s memories. One morning in the winter of 1843–1844, when she entered Lucy Mack Smith’s room, Jane remembered, “she said ‘Good morning, bring me that bundle from my bureau and sit down here.’ I did as she told me. She placed the bundle in my hands and said, ‘Handle this and then put [it] in the top drawer of my bureau and lock it up.’ ” Once Jane had followed her directions, Smith explained:

“‘Do you remember that I told you about the Urim and Thummim when I told you about the Book of Mormon?’ I answered, ‘Yes, Ma’am.’ She then told me I had just handled it. ‘You are not permitted to see it, but you have been permitted to handle it. You will live long after I am dead and gone. And you can tell the Latter-day Saints that you was permitted to handle the Urim and Thummim.’ ”4

According to Joseph Smith’s own history, though, he returned the Urim and Thummim along with the plates to a divine messenger when he was finished translating the book, so Jane joined the Church far too late to handle those precious artifacts of the Church’s founding. Instead, it appears that Joseph Smith and those close to him generalized the term “Urim and Thummim” to refer to “any stones used to receive divine revelations.” This included both the interpreters Smith had received with the Book of Mormon plates and other seer stones, some of which Smith had owned even before he began having the visions that would ultimately lead to the founding of "Mormonism."

In 1830 Smith gave one of these stones to Oliver Cowdery, who had helped transcribe the Book of Mormon as Smith translated it. Cowdery kept that stone until his death in 1850; it was later donated to the Church. But Brigham Young stated in 1853 that “Joseph had 3 [other seer stones] which Emma [Smith] has.” It is likely that Lucy Mack Smith used the term “Urim and Thummim” to describe some combination of these stones and that Jane handled these instruments at Mother Smith’s direction.

In an 1899 conversation with Elvira Stevens Barney, a white Latter-day Saint woman, Jane described the object Mother Smith had allowed her to handle: “The instrument as near as I can describe it, which I handled, was made of some kind of metal, because it was so very heavy. It was firmly attached, one piece upon another. One piece seemed to be about the size of my wrist,” which Barney interjected was “good size and not perfectly round.” Jane went on: “The other piece was not so large. These were set upright in a circular base.” This description of stones set in an armature sounded more like the original set of interpreters than it did like the “ordinary” seer stones that Jane probably handled. But Jane was careful to quash speculation about the objects to which she had access, telling Barney that Mother Smith “did not say that Joseph used it to translate the Book of Mormon.” By quoting Lucy Mack Smith’s remark that Jane would be able to “tell the Latter-day Saints that [she] was permitted to handle the Urim and Thummim,” Jane made clear the intimate access she had to the foundations of the Church as a trusted member of the Smith household. Handling any of Joseph Smith’s seer stones was a privilege few Latter-day Saints could claim.5

Lead image of the Pioneers of 1847 gathered for a group photo in 1905. Jane and her brother Isaac are pictured in the group. Savage, “Utah Pioneers of 1847,” Princeton University Library.

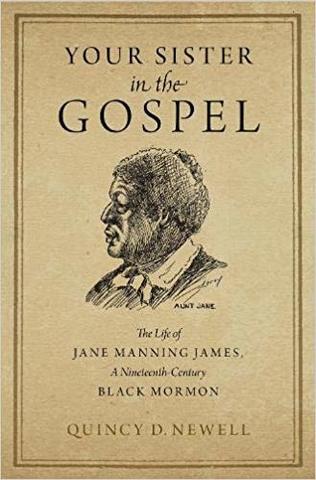

[1] Jane Elizabeth Manning James, “Autobiography,” reprinted in Quincy D. Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel: The Life of Jane Manning James, a Nineteenth-Century Black Mormon (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 146.

[2] Maria J[ane Johnston] Woodward, quoted in “Joseph Smith, the Prophet,” Young Woman’s Journal 17, no. 12 (December 1906): 544. Woodward used her married name when she recorded her memories, but at the time she lived in the Smith household, she was known by her natal surname, Johnston.

[3] Maria Jane Johnston Woodward reminiscence, April 1902, in George H. Brimhall to Joseph F. Smith, April 21, 1902, MS 1325, Box 20, Folder 1, image 23, Joseph F. Smith Papers, 1854-1918, LDS Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[4] James, “Autobiography,” 146.

[5] On the use of “Urim and Thummim” as a general category of stones, see Richard E. Turley, Jr., Robin S. Jensen, and Mark Ashurst-McGee, “Joseph the Seer,” Ensign, October 2015, https://www.lds.org/ensign/2015/10/joseph-the-seer?lang=eng. For a detailed discussion of Smith’s various seer stones, his use of them, and their subsequent chains of custody, see Michael Hubbard MacKay and Nicholas J. Frederick, Joseph Smith’s Seer Stones (Provo and Salt Lake City, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, in cooperation with Deseret Book Company, 2016), 29–43, 45–57, and 65–85. For Jane’s conversation with Elvira Stevens Barney, see Barney, “Jane Manning James,” Deseret Evening News, October 4, 1899, 6, reprinted in Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel, 142-43. For Jane’s quotation of Lucy Mack Smith, see James, “Autobiography,” 146.

"Dear Brother," Jane Manning James wrote to Joseph F. Smith in 1903, "I take this opportunity of writing to ask you if I can get my endowments and also finish the work I have begun for my dead. . . . Your sister in the Gospel, Jane E. James." A faithful Latter-day Saint since her conversion 60 years earlier, James had made this request several times before, to no avail, and this time she would be just as unsuccessful, even though most Latter-day Saints were allowed to participate in the endowment ritual in the temple as a matter of course. James, unlike most Latter-day Saints, was black. For that reason, she was barred from performing the temple rituals that Latter-day Saints believe are necessary to reach the highest degrees of glory after death.

A free black woman from Connecticut, James positioned herself at the center of Church history with uncanny precision. After her conversion, she traveled with her family and other converts from the region to Nauvoo, Illinois, where the Church was then based. There, she took a job as a servant in the home of Joseph Smith. When Smith was killed in 1844, Jane found employment as a servant in Brigham Young's home. These positions placed Jane in proximity to the religion's most powerful figures.

Your Sister in the Gospelis the first scholarly biography of Jane Manning James or, for that matter, any black Latter-day Saint. Quincy D. Newell chronicles the life of this remarkable yet largely unknown figure and reveals why James's story changes our understanding of American history.

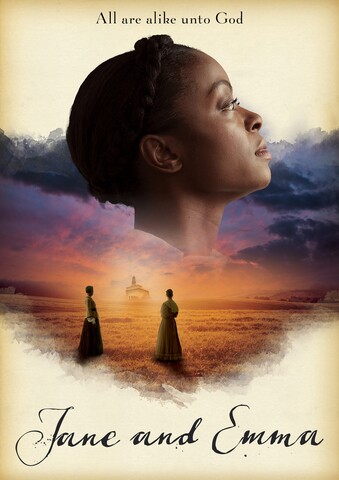

Watch this beautiful movie inspired by Jane's life. Sister Jane Manning, a free black woman and convert to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, returns to Nauvoo to find that Joseph Smith, her prophet and friend, has been assassinated. Jane spends a ceaseless night with his widow, Emma Smith, sitting watch over the body of the Prophet, as a whirlwind of memory, loss, and confusion leaves them wondering how either one of them will be able to move forward. Through the long night, Jane wonders if the Prophet's promise to extend the blessings of eternity to her has died along with him. Join these two remarkable women of faith on an imagined night that reveals the essence of their complex, raw, and ultimately beautiful friendship.