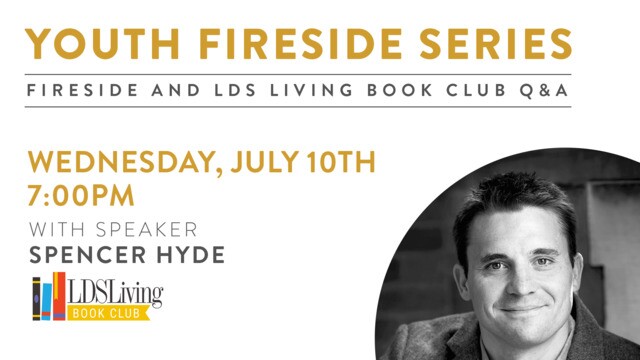

Last Wednesday, the LDS Living Book Club and Deseret Book hosted a fireside and Q&A with BYU English professor and author Spencer Hyde. Spencer has lived with severe OCD his entire life and based the book Waiting for Fitzroughly on his own experiences.

Watch the video below or keep scrolling for a transcript of the event as well as some bonus questions Spencer answered afterward.

Transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Colin Rivera: Everyone, thank you so much for coming out. Welcome to this combined event, which is a combined Deseret Book youth fireside event and an LDS Living Book Cub Q&A event. So thank you so much for coming. We have the amazing Spencer Hyde with us and his mom Cindy. We're excited to hear from them. Spencer is the author of Waiting for Fitz, which is our current LDS Living Book Club selection for this month. We've been reading together and basically how the Book Club works is we all read a book together and we get some insights from the author throughout the month. And then once during the month, we kind of all get together and hear some live insights from the author. And we're privileged to be able to have that be combined with a fireside about some of the deeper and more complex issues that the book touches on. We're grateful for Spencer for being here to do that.

Spencer Hyde spent three years during high school at Johns Hopkins for severe OCD. He was particularly suited to write this novel because he's lived through the protagonist's obsessions. Spencer worked at a therapeutic boarding school before earning his MFA and his Ph.D., specializing in fiction, short human pieces and essays. He wrote Waiting for Fitz while working as a teaching fellow in Denton, Texas. Spencer and his wife, Brittany, are the parents of four children. We're really grateful that you guys can be here today. And we're grateful that Spencer and his mom could be here.

Spencer Hyde: I wanted to keep this really informal, more casual, and just really talk about the story behind Waiting for Fitz, which is in large part my story, but combined with many others who have their own individual struggles. So I was going to start from well, not from the very beginning, but just from childhood.

I noticed as a kid that I was very particular. How many of you avoid the cracks in the sidewalk? Show of hands? Yeah? So I thought you know, "That's normal, I'm avoiding cracks in the sidewalk, that makes sense." But I was also doing other things. I was counting things. And I thought, "Well, that's got to be one of those things. You're just counting things. Everyone does that, I'm sure." And then when I was about six or seven, I was in the car. I still remember it because there was this infomercial. And if you read the book or have read the book, you'll notice I make fun of those a lot. Because they're hilarious and they're all the same. But there was one on the radio that said, "You know, do you count things?" And I thought, "Yeah, most people do." And they said, "Do you count things in specific numbers and get upset if things aren't the way you want them to be?" Well, yeah, I do. And they said, "You might be suffering from OCD," after they listed a bunch of other things and I thought, "What's OCD?"

From there, I just kind of thought, well, maybe I do have OCD, but it doesn't really matter. It's not debilitating, I can still get on with my life just fine. And here I want to introduce my mother because she's going to have information that I don't, because when things started getting bad, it's almost as if horse blinders were put on, or like I was completely knocked out. When my parents were called to be mission presidents in Maryland we were brought into Elder Maxwell's office. I don't remember that meeting at all because I slept through the whole thing. It was a really soft couch. I was actually taking medications at the time, things were at their worst as far as the OCD goes. So she'll remember things that I don't and she has more insight on specific moments that I do. So this is Cindy Hyde, my mother. My wonderful mother. And whenever you want to jump in and correct me or add something just let me know and we'll keep going from here. So I was about nine or ten when it started getting worse.

There's usually a trigger event for OCD. Spencer had OCD things before the trigger event. But I didn't really notice them as something that wasn't supposed to be. -Cindy Hyde

Cindy Hyde: There's usually a trigger event for OCD. Spencer had OCD things before the trigger event. But I didn't really notice them as something that wasn't supposed to be. He used to have to line up his cars to go to bed. When he got the scissors to cut a little piece of fabric out of one of his clothes to see what that felt like, he had to cut the same piece out of everything he owned. So there were things like that. If he got dirty on the playground I would get a call from school and he would need me to bring him a clean shirt. I had two boys before him, who would come home from school looking like they had worn that shirt all week. So that was unusual, but I just thought, "He's just clean."

Anyway, my father passed away and the next day Rob's mother passed away, my husband's mother. And that was the trigger event for Spencer. He was in third grade at the time and I was putting those obituaries into the children's histories and Spencer could no longer come into that room anymore. And every time my mother left or any of us left Spencer would have to hug us and tell us that he loved us. He felt like he had missed that with my dad and his grandma that had passed away.

SH: I was really close to my grandpa. He's the one who started encouraging me to write stories. I handed him things and he was like, "Oh that's really interesting!" Even though they were bad. We saved some of them and they were not interesting. But I was happy to feel that encouragement. But here's where I think of a part in Waiting for Fitz where I talk about Pascal's Wager. And it's kind of how I thought of those times. I didn't have a term or theory for it until later. But Pascal's Wager is, if there is a God and you believe and you know, and die and go to heaven, that was a good thing because there is a God. If there's not a God, and we believe in Him and we don't live a good life, it doesn't matter because he's not there. If we don't live a good life and he is there, that's not good. So with OCD, I know it sounds crazy not to go into this room. But what if something happened. My OCD is telling me, you know, if you go in, you're going to feel this immense depression that something bad would happen to others in the family close to you unless you wash it off. And I thought if I just avoid that room, I'm good, I'm safe. So I started thinking in those terms, which isn't necessarily healthy, but it was a way to cope at that time.

Spencer said to me, "Mom, I don't think I can believe what you and Dad believe." And I don't know what happened, but I know the words were put into my mouth. And I said to Spencer, "That's okay. You don't have to believe it. You can just know that Dad and I do." -Cindy Hyde

CH: When Spencer hit puberty is when things really escalated, at age 12 when he went to junior high school. Spencer was the kind of person that he never brought one friend home from school, he brought five. When it got bad, pretty soon there were no more friends and he was living in is rituals. I remember one time driving down South Temple and was taking him to school and we were by ourselves. And Spencer said to me, "Mom, I don't think I can believe what you and Dad believe." And I don't know what happened, but I know the words were put into my mouth. And I said to Spencer, "That's okay. You don't have to believe it. You can just know that Dad and I do." And I can see Spencer's whole body just relax. I think that was something that was so hard for him to say to me and knowing that he said it to my husband also because he knew how important our religion is to us. He said later that he felt like somebody had taken a piano off of his back. Rob and I later read a book called The Boy Who Couldn't Stop Washing. And in that book, she says how hard religion is for people with OCD. Because in religion we feel so many things. People with OCD are feeling so many things that it's hard to tell which one it could be.

One of the first things that Spencer did that I noticed was he walked by the counter and he knocked his hand. And then he backed up, and he knocked it twice and he kept going. And I was like, "What are you doing?" He goes, "Number one is bad, number two is good." And he kept going.

SH: Which, by the way, the bathroom in this Deseret Book store is not a great place with those with OCD. It's got the one with the hand dryer that you stick your hands in. And they always hit the side and you think you need to go wash again. And there are no paper towels so you are waiting for someone to walk in and open the door. I still have these things. They're not gone.

But yes, religion was very difficult because I thought, just give me the numbers, right now. I'm listening to talks, and I'm counting different words, and the things they're doing. Or I'm looking at different colors in the room. I'm not really paying attention and I'm not really fully there. And as far as the friends go, they were always kind to me, but mental illness can be a very selfish thing. You feel very selfish at times. And, you know, not only am I struggling, but I'm causing others to lose sight of what they're struggling with because they're invested in my life. And I'm very grateful for that but man, I feel selfish. I'm totally in my head. I don't know anything that's going on with anybody else because I'm always thinking about when's the next bathroom stop... Right? When we moved to Maryland, even going in the hospital I was stopping at every bathroom along the way to wash it off of me. And yes, I still remember certain clothes I'd be wearing in different situations. If they were "contaminated", I couldn't wear them. I just put them in the closet.

CH: So we had a missionary new to the mission, and she did not have an arm. Well, Spencer had gone with Rob to pick up the new missionaries, and he had his new Sunday clothes on. And when he got home from that the missionaries staying at our home that first night. This sister's sat in a chair, and then went up and slept in the bedroom, and was gone the next day. And the next day, all of Spencer's clothes had been thrown away. Spencer could no longer sit in that chair that she had sat in and he never went again into the bedroom that she was in. I said to Spencer one day, "Spencer, surely somewhere inside of you, you know your arm is not going to fall off if you sit in that chair." And he looked at me. And he just had this very thoughtful look on his face for a while and goes, "Yeah Mom, I think it is in there somewhere. I just don't know where."

We often have labels in society, like the "autistic kid" or the "black person," instead of "the person who is autistic" or "the person who is black." I think it's important to put the person first. But at the time, with that kind of OCD, it was hard for me to separate anything from anything else. It was all just a mess. Which is what caused me to be more depressed and turn inward. And thinking that I would never crawl out of that hole. There were a lot of hopeless moments. -Spencer Hyde

SH: I remember that sister. She was wonderful. One thing I tried to do in Waiting for Fitz is separate the person from what they deal with. We often have labels in society, like the "autistic kid" or the "black person," instead of "the person who is autistic" or "the person who is black." I think it's important to put the person first. But at the time, with that kind of OCD, it was hard for me to separate anything from anything else. It was all just a mess. Which is what caused me to be more depressed and turn inward. And thinking that I would never crawl out of that hole. There were a lot of hopeless moments. There's one scene in Waiting for Fitz where Addie takes, you know, 45 minutes to walk down the stairs. One of my buddies called me after he read the book. And he said, "Look, I really enjoyed it, I like it. But that first chapter when she walked down the stairs, that was exhausting." And I said, "Good. I want you to feel exhausted." Because that was every moment of every day. Even trying to get to sleep, that's when it got even worse, you know. Thoughts would come and I'd have to go wash. But the has a story has a good ending.

When my parents got called to Maryland. Well, you know this part better than I do; just getting to Dr. Riddle.

CH: So when we left for Maryland, everything got worse than it had ever gotten. Because change is very hard for people with OCD. When there's change, things escalate. And my mother said to me one night, "You two simple fools are not going to go on a mission are you when you have a son that is that sick?" And I said, "One of two things is going to happen. Either we're going to go where Spencer's going to get help. Or we're going to go to Africa and he's going to be healed. And I'm hoping for Africa."

So when we got our call, it was to Johns Hopkins. I mean, it was Maryland and Johns Hopkins is in that area. When we were in the MTC, one of the sisters stood up during the sisters' session and asked about mental illness. And she talked about how she had two identical twins, who had mental illness and were on missions. And she was from the area where I was going. So afterward, I went up to her and asked her about the doctor that she saw. And she said, "oh, he is just amazing." And we can get you an appointment. So we went into the office where the mission president and wife can use the phone and she got on the phone, called the doctor and we had an appointment the second day after we got to Maryland. So Spencer and I, not knowing how to get to Johns Hopkins, were driven by the assistants down there. And we met with this doctor. And after he talked to us for a little while and said, "You know, the number one specialist in the whole country for adolescent OCD happens to be here at Johns Hopkins." And he said. "Once a year, he has to take time on the floor. This is July. He's head of psychiatry, he doesn't ever take July. But let me go find out when he's going to be on the floor because that's when we need to get Spencer into the inpatient unit." So he comes back into the room and says that Dr. Riddle is on the floor for July. He said this has never happened. But when people know the doctor was coming, the place is booked. So he said let me go see there was a spot for him on the floor.

He came back to the room and he said, "Who are you?"

"I'm Cindy Hyde and this is my son, Spencer."

He said, "No. Who are you? And why are you here?" And I explained to him about our mission. And he said, "There is a room on the floor with Dr. Riddle. And it's a private room. And I'm sending you up to information. And we're going to admit Spencer."

SH: I had just turned 15. And the stewardess surprised me on the way over and gave me a first-class seat and I slept the whole way because I was still on those medications. It's like an elephant tranquilizer. I was always sleeping. But yeah, we got to the inpatient unit. That was really hard. I mean, I certainly needed help, I wanted help. But I, you know, I hadn't been away from my family. I hadn't done anything on my own. Because I needed the comfort of home when I was struggling like that. She was talking about change, I didn't want any change. I wanted to be in the back in my room, I knew where the sinks were. So I got it, and she left. And then my dad came back later that night with some of my things.

CH: Okay, this was kind of an important part. We had all been fasting and praying for over a couple of years now. Now it's two years in the making when Spencer was really, really sick. And we haven't seen our happy Spencer for a long time. Dr. Taber is taking the information for us to be admitted. And for some reason, I couldn't stop crying. And this was unusual for me. And so I went into the other room and I called my husband who was interviewing missionaries. And he said, "Oh my gosh, we need to stop. You know, we need to be strong for Spencer." And I said, "I'm trying but I'm torn!" So Dr. Taber went and got Dr. Riddle, who was the specialist. And he came in because they were afraid I was not going to be able to leave Spencer, because Spencer is about as tight as you can get to me saying, "Mom don't leave me here. Mom, don't leave me here."

So Dr. Riddle says to me, "Your son is very sick. And he has not been helped yet and I am going to help him." So we left Spencer there. And I still remember the sound of the metal doors when they shut. And they just vibrated through my soul. And Dr. Riddle told me I was only allowed to come to see him for an hour a day. And Spencer said before I left, "Mom, remember, this is what we have been fasting and praying for."

I knew that this was the answer to all of our fasting and all of our prayers. And this was the means that the word was provided for us to help our son. He wasn't going to be healed, but he was going to be helped. -Cindy Hyde

So the assistants are driving me home and I am crying the whole way home. I need some help. I need to feel some peace. I need to know that this is right. I need Him. And then I thought about where I was in the Book of Mormon because that's what I do when I need help. I open the Book of Mormon and start reading. I didn't know where else to read and so when I got home I sat down and I opened it and I was in chapter 16 of Alma. And I got to verse 21. And it said, "Do you think you can sit upon the thrones and not make use of the means that I've been provided for you?" And feeling started at the top of my head and went through my whole body. And I knew that this was the answer to all of our fasting and all of our prayers. And this was the means that the word was provided for us to help our son. He wasn't going to be healed, but he was going to be helped.

SH: I love hearing it from my mother because I didn't experience it that way. Because I wasn't able to feel those things at the time. In religion, you almost have to be kind of vulnerable, right? Just hang on to those around me who know what they're doing. And those who trust. And trust that they're taking you in the right direction until you can get on your own feet, right? I'm good at mixing metaphors. You'll notice in the book. I stole Taborn because I wanted to give him a little shout out. And Dr. Riddle, that's just too good not to use. But in the hospital, one thing I noticed, which is I mean, they're not catering to the OCD people, but everything's routine, right? You have the person who's in charge of the pills, they get them the little cups. You drink them, you move on. You go to this meeting, you go to the next meeting, here's your schedule for the day. I hated schedules like that. But I noticed that everything was a routine. We had all these rituals. And that's why you'll see in the book, I joke about them sometimes because I looked at them and I imagined Dr. Riddle, and Dr. Taber look at each other like "Hey man, I was going to wear the white coat today." And he's like, "We all have to wear a white coat. I like to put my glasses on real quick, I'm going to do that today, you can do it tomorrow." They have the same routines. And the more I read about the Theater of the Absurd and Waiting for Godot— which the title references and the book references—I started realizing that life is a series of rituals unless there's something to give it meaning, right? I mean that's all it is, is a ritual unless we have some purpose. Unless we have something in it for you and me. So hearing that helps give it meaning because at the time I was just hanging on.

CH: So I came home from the hospital. I'm a wreck. My husband gathers the family and lets them know what's happening and why Spencer's not home. And he said, "You know what, let me take his pillow down to the hospital because you're in no condition to do that." He came back in the very same position I had come back in. So much for his bravery. But the next morning at seven, the telephone rang, and it was Doctor Riddle. And he said, "I want to study your son. I want to take him on as a private patient." Doctor Riddle takes no private patients. He continued. "I would like to take him on as a private patient. I want to see him every day. And I might want to see him for a long time every day. But I'm going to let you come and get him this morning. As long as you promise me to bring him every time we want to see." So that was a miracle.

Dr. Riddle had started seeing Spencer at first every day and eventually went to once a week. He wanted to take Spencer on as a private patient because he had never seen a case like Spencer before. In all of his stories of OCD adolescents, there was always something that he felt like that might be the cause. Whether it was a divorce or drug addiction, or, you know, there were so many things. With the mother going on drugs when she's pregnant, or this or that. He said, "So far I've had five conversations with Spencer and I want to treat him." Dr. Riddle treated him for three years and never charged us. Because he didn't even know how to charge us because he didn't take patients.

SH: I'm just thinking about Dr. Riddle's office. I remember going in there and feeling trapped because I was looking at his bookshelf and I had a lot of choice words for the books he had on the shelf. I mean, he didn't have great taste in reading, I didn't think. There was kind of a haze around my life. And so I just sat back and listened. I didn't really become myself again until I honestly finally found the right medication. And then the right behavioral therapy.

CH: So Spencer was seeing Dr. Riddle for about seven months, and nothing was changing. When we would go into Johns Hopkins and here was Spencer's worst nightmare. It's not like going to an office. We had to walk through a hospital full of sick people. People in wheelchairs. People with all kinds of things that they were dealing with. Spencer would put a hood on and try and hide all the way there. But he knew every bathroom all on the first floor, and we take the elevator around and he'd see the bathroom, right before we got to talk to Dr. Riddle.

SH: And it's not because of the people or their illness. I thought that if I was around that, that it would somehow like, the OCD was saying, "this will transfer to someone you love. If you don't go wash your hands, everything in this hospital, maybe this consuming bone cancer will immediately transfer to your sister or your brother." And I thought, "well that sounds ridiculous. But I need to be safe. I'm going to go wash my hands. I don't want anything to happen to anyone I love."

CH: Spencer's hands were raw and bleeding. Every night I would go in after he went to bed and put Aquaphor on his hands. So Doctor Riddle has been seeing him for about seven months. I was at every appointment with Spencer. And he asked me, he said, "I'm stumped. And I feel like I should be further Spencer at this point at seven months. I have two colleagues, one Chicago, one in Arizona. Will you go with Spencer and see those two colleagues? And I said, "Yes," not knowing what the Church would say if I said, "I'm going to Chicago and Arizona with my son while I'm on a mission." But anyway, I said to Dr. Riddle, "I've had a feeling." And Dr. Riddle said, "You've had a feeling?" And I said, "Yes, I think you should try Ritalin." Now, if anybody looks up Ritalin and OCD, that's a very, very bad combination. Dr. Riddle looked at me and said, "I will never, ever, put him on Ritalin. We're done with that." Then I said, "No, let me explain to you about what a feeling is." And I explained it to him. And he said, "Well, we just started a new medication. So we're going to go with that one for two weeks, and in two weeks, we'll talk about this again." So in two weeks, we came in, and the first thing I said was, "Can we try Ritalin?" And Dr. Riddle had his head down, he was writing. And he looked up over his glasses and he said, "You are not going to leave me alone on this are you?" And I said, "No." He said, "The feeling." And I said, "That's right, the feeling." And he said, "I am going to give you five days. Five days of Ritalin. And when that's done, you will never talk to me about it again. Is that a promise?" I said, "That's a promise." So we went out with five days of Ritalin. On the second day, Spencer came into our bedroom. And he said, "Mom, Dad, I'm back."

SH: And that's the story. That's pretty much how we got to where we are. Not that it's gone, right? I don't want you to think that it magically disappeared. My wife still graciously opens doors for me so I don't have to. I still count things. My mind's going a mile a minute. I'm looking at different things. I'm counting things all the time, still. But I've learned to deal with them. And some of that was exposure therapy, working with different behavioral therapists. You know, they'd say something like "cancer." And they look at me and I'm like, "I know the bathroom right out the door", and they're like, "Don't. You can't for five minutes." Which is torture. But five minutes later, I realized we were talking and I had forgotten about it. So it's just those steps to retrain the brain. So that's the story. I'm happy to take any questions.

CR: We're going to get to as many as we can, but we're running a little bit short on time.

For those who are here to hear your story, but maybe aren't as familiar with the book, would you give just like a two-minute overview of the book, so some of these questions become a little bit more relevant.

SH: Yeah, absolutely. So in Waiting for Fitz the germ of the idea was in the psych ward at Johns Hopkins. But this story is about a group of teens, two of whom break out of a psych ward in Seattle, to track down the past of the main male character. The protagonist, Addie—I chose a female protagonist to give me the distance I needed. I started with a male protagonist, and it felt too close to what I was dealing with, and I needed the separation. So Addie Foster is the main character. And in the psych ward, she meets Fitz. He's dealing with schizophrenia, and they have a group of friends in there. Didi, who was a pathological liar. Wolf who is looking for his horse. And then you have a few others dealing with very specific things. Didi also has Tourette's. But again, I wanted to create a fun story, but one that also touches on important things like forgiveness, and hope, and love.

CR: Awesome. So the first question I wanted to ask is, are any of the actual characters and people and events depicted in the book, something that happened to you or is it loosely inspired by experiences you've had?

SH: I'd say, loosely based on my experience. Like Fitz, I have a friend whose wife has schizophrenia. She read the pages. I have a friend who deals with Tourettes's. I had people read the pages and kind of tell me, you know, this doesn't feel right, because I wanted to get it as accurate as possible, as close as possible with their experience. But yeah, it's loosely based on my experience.

CR: Can you tell me a little bit about what inspired you to put the pen to paper and publish a book like this? Obviously, the subject matter is really meaningful to you. But why actually write a book?

SH: I think that started with the natural world, honestly. There were some things I was fascinated by, that are in the book. Like the size of a great blue whales heart, or the Kirkland's Warbler, and how I was intrigued by how fascinated people were with these little birds nest in Michigan and the Bahamas. And it only nested in trees that are a certain height. And those trees only come to be when a fire releases the seed in the ground. I was fascinated by these things. So those ideas are peppered throughout the book. But the heart of the book came from my reading of Waiting for Godot and my experience with those and thinking about rituals. And how I wanted to tell a story where a character realized this, right? My life is a series of absurd rituals until something or someone gets it. And so I wanted a character to go through that experience.

CR: We have a question from Kevin, who wrote his question on our LDSL Facebook feed. He said, "My spouse does the same things that you mentioned during your fireside and was never sought treatment until now. How can I be supportive of that?

SH: Love them. I know that sounds simple. Love them and allow them their space to deal with the issue. For example on Halloween last year, my wife bought us clothes, we're going to be the Weasleys. But I got home and saw the costume on the bed and immediately had a bad association with it. And I thought I can't wear that. And I'm at a point where I new behaviorally, it would be good for me to wear it and get over it. But I'm also kind of just not feeling good, like let's just move passed this one. And she was so charitable and kind and said, "That's okay, we'll do something else." And I think allowing the person to figure it out at their own pace is the most important.

CR: What lessons do you hope that people take away from the book?

SH: We touched on this a little bit earlier, but I hope they take away the idea that the person is much more important than anything they're dealing with. But also when everyone is dealing with something. And remember the person first, and to love them as best you can. I think that's most important. And this one idea one central idea also was the idea of forgiveness in the book. I think we often don't believe that. Forgiveness works for everyone else. But maybe not for me, which I think is true of mental health. Other people can get help. But not in my situation. Mine's different, right? It's so individual which I talk about in the authors note in the beginning. But it doesn't mean that you can't empathize with others. And I hope that you can feel some of that in these characters.

CR: Thank you. I have a question for your mom. This is from Sharon: "How would you handle school with Spencer, knowing about his OCD? What did that look like in his education?"

CH: I would actually go in and talk with the teachers. Because if something was said in the classroom, when Spencer hadn't yet turned in his homework, if something was said that was contaminating, he couldn't open his backpack, because then everything in the backpack would be contaminated. So he would not be able to turn his assignment in if something has been said, that had bothered him before that time. So I've talked to every teacher. The other thing that we did is Dr. Riddle did not want Spencer getting up for early morning seminary. And so I went to the stake president and was set apart as a seminary teacher. And I taught Spencer at home.

CR: This is a question from Brian who is here tonight. I have a friend who because of depression, anxiety and addiction has lost his belief in God, how do we help others and ourselves when we face these sorts of challenges?

SH: I think it goes back to loving him and allowing him to space, but also recognizing that he may not be in a position where he can even understand what you're trying to tell him about religion. It's like my mom trying to describe her feeling to Dr. Riddle. Well, that doesn't work for me, right? I don't think in those terms, I don't understand what you're trying to say. And when you're dealing with severe depression, like I was at one point, it didn't matter what other people said. I was in my own world. But what's most important is that you are there and that person emerges for the smallest thing, right? The smallest question, the smallest favor or if they're willing to respond to you. Keep the conversation going and worry about friendship and loving them before anything else.

CR: Thank you. We have two more questions. This is from Lindsay who is here. She says, "When struggling mentally or emotionally, how do you know if you should just rely on the Savior or if you should seek out therapy and/or medication? What is a good balance? How do you know what's best for you?

SH: I'm open-minded. We've been given so much, right? Dr. Riddle, I still remember talking with him once and he said this was in 2003, he said, "We have learned more in the past 10 years about medicine than in the 100 years before that combined." And imagine what's happened since, 2003-2019. We have incredible means that have been given to us. We are all very fortunate to have access to these means. If you don't have access there are a lot of groups out there focusing on these specific issues, focusing on suicide prevention, focusing on depression and OCD. So get out your phone and search. But I'd go find help. Especially looking up those who specialize in our area, right? You Google doctors specializing in OCD.

So often you find people who say, "I don't want to take anything because it changes my personality, or I don't want it to change me." But as I've had children that have dealt with mental illness, what it has done is given them their lives back, and given them the ability to live a life. -Cindy Hyde

CH: So often you find people who say, "I don't want to take anything because it changes my personality, or I don't want it to change me." But as I've had children that have dealt with mental illness, what it has done is given them their lives back, and given them the ability to live a life.

SH: I had a friend in college while I was having a tough time struggling with some depression. And that man said, dead serious, he said, "Why don't you just go on a jog? Just work it out, you know?" And I thought, "Well, I guess if you've never grown up around mental illness, we also can't fault people for having these ideas. right? If that's how they work through their problems that's wonderful." But I had to talk to him about you know, that doesn't work for me. That might make it worse. So I think educating people as best you can, and then allowing them space to grow.

CR: Thanks so much. One more question. This is from Callie from our Facebook feed. She says. "Now that you are on the other side, what steps would you recommend to someone in this situation?"

SH: I imagine the situation on the other side? If I'm understanding the question right, I'd recommend seeking help immediately. I've had a few emails after people read the book. And I remind them, I'm a doctor, but not that kind of doctor. So find help, and then lean on those close to you for support. And just don't give up. This is an important question. And whenever someone asks about this, about what do I do when I'm in it, when I'm in the fire, when I can't breathe? I think about that piano on my back, that weight. I think about my raw and bleeding hands. I think about the young boy on the bed when I first got to the psych ward. He was only a few years younger than me, when I could have sworn he was like five years old. My heart broke. And I thought I'm struggling with a lot. But he's already here. What is he struggling with? And for me, the whole world of fiction, the reason I write is to give people an experience that they wouldn't normally have. To teach them about things they might not normally learn about or know about. And have them experience another life and learn to empathize. Because fiction, good stories, it's practice, the practicing accountability. And practice how to live through books. And I spent a lot of my time and books. Not just the Book of Mormon, but a lot of different books when I was at my worst. And I think that it might sound over the top, but words saved me.

After the fireside, Spencer answered some of the questions we didn't have time to get to during the live event and expounded on some of the answers he already gave.

What do you think the best way to support someone with OCD is? Listening? Or, what is the best way someone supported you?

A great question. So often those struggling with mental illness are consumed by their own thoughts so much so that they can't quite hear or see anything else. I think what matters most here is proximity. You need to be close, you need to let them see you close, let them know you are there, even if you don't have answers for them. Sometimes that meant sitting in the car with my brother, William, knowing he wasn't going to ask me questions about OCD or depression or anxiety. We could just be. We could watch a soccer game together and I knew there was no judgment. Nothing but time together. I think that's the best way to support someone in that situation at times, but it varies for each case. Love them. Be present.

What are some things that help to boost your creativity when you're struggling to write?

Get outside. Go for a hike. Go for a swim. Watch a comedy sketch. Read a book. I find when I invest my time in other works that inspire awe, I start to gain traction in my own work. William Trevor said if you want to be a great writer, you need to be an even better reader. Annie Proulx said the same thing. In fact, it's hard to find a writer who doesn't know this very thing: if you want to be a better writer, be an amazing reader. Consume everything you can get your hands on, and I promise it will provide fuel for your own creative endeavors. There is something of the artistic community in each piece, something of a collective hunger to create that will spill over into your own work. Look to others, and you'll find yourself.

When struggling mentally or emotionally, how do you know if you should just rely on the Savior, or if you should seek out therapy and/or medication? What is a good balance? How do you know what is best for you and your needs?

I think Brigham Young's advice is quite fitting here: "Pray as though everything depended on the Lord and work as though everything depended on you." If you are thinking it might be a good idea to seek out therapy, then do it! If you are questioning it in the slightest, go see someone. If someone you love thinks it might benefit you, show them you appreciate their concern and trust them and go see someone. The Lord has provided us with incredible means. I remember at Johns Hopkins when Dr. Riddle told me that there had been more advancements in medicine from 1993-2003 than there had been in the 100 years before it, combined! That's incredible. Imagine how far we've come since then. You have means available. You have people who love you and want to see you happy. Do all the work you can during the day, then fall on your knees and find the balance.

I have a friend who because of depression, anxiety, and addiction has lost his belief in God. How do I help this friend face that challenge?

This friend doesn't need someone to tell them about God or religion in any way. This friend, in fact, likely cannot even face the smallest requirements of living let alone grander thoughts of greater significance. The timeline is not eternal, but second to second. I don't think that's an exaggeration either, having been in that sink myself. You can help this friend by being proximate, by being present, by loving them. Be nearby so any moment of emergence, any sight of hope, is one you can capitalize on. Remind them they are loved. Do that by being there and not putting any pressure on the person. They have enough weight on them as it is. Show up and offer to carry the load, but don't go in with expectations--go in with the idea of charity and presence on your mind.

What do you hope that people will take away from Waiting for Fitz?

A lot. I hope you enjoy the story. I hope you connect with the characters. I hope you empathize with mental illness and forgiveness and mercy and hope and all themes present in the book. I hope you understand more about what it means to be a human and exist on this earth at this time with people struggling from numerous things, be it OCD or understanding what it means to love or forgive or befriend. You are okay, just as you are. I hope you understand that.

Now that you are on the other side, what steps would you recommend to someone in your previous situation?

Don't give up. You are needed. You matter. You are loved. People are waiting for you. Take your time. There is no deadline, there is not a requirement, there is no line you must reach. We will meet you where you are. There are people waiting to help you carry the weight. Let them. There are those waiting to love you more fully. Let them. There are those present who would sacrifice anything and everything to get you back. Let them. Don't feel you are selfish. Don't feel guilt for your struggle and how it has presented itself. Don't feel you have done anything wrong. You are never so low we can't reach you. Your OCD or depression or schizophrenia or anxiety is never so loud that we cannot cry out over it and be heard, even from a thousand miles away. We will be heard. You will hear us. We are not going anywhere, so take your time. We'll be here, present, proximate, filled with love. You are wonderful. We are waiting for you. You are worth waiting for.