Russell Osguthorpe: Attachment, Relationships, and God's Plan

Latter-day Saints may best recognize Russell Osguthorpe's name from his time as Sunday School general president. But they may not know he has a background in psychology and was serving as a stake president when he noticed that healthy attachment could be developed in relationships as long as a desire for improvement existed. Since then, he has been devoted to better understanding attachment theory from an academic, clinical, and spiritual perspective. In this week's episode, in honor of Valentine's Day, we'll discuss the importance of developing healthy attachments with God and with those around us.

We need to come to know God as He knows us. And we need to come to know His children as He knows His children. When we do that, we will be attached and [that attachment is] stronger than a relationship or a connection.

Episode References:

Brother Osguthrope’s book: Filled with His Love

Brother Osguthrope’s podcast: Filled with His Love Podcast

Book about family estrangements: Fault Lines: Fractured Families and How to Mend Them

Quotes:

“There are many in the world who are dying for a piece of bread but there are many more dying for a little love.” – Mother Teresa

“It is a time-honored adage that love begets love. Let us pour forth love—show forth our kindness unto all mankind, and the Lord will reward us with everlasting increase; cast our bread upon the waters and we shall receive it after many days, increased to a hundredfold. Friendship is like Brother Turley in his blacksmith shop welding iron to iron; it unites the human family with its happy influences” (Joseph Smith, Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, p. 316.)

Show Notes:

2:19- Attached?

9:05- Hope for Change

12:42- Initial Interest

14:25- Parent-children Relationships and Ability to Attach

19:52- Covenants and Attachment

22:29- Sibling Relationships

27:20- Words That Give Life

30:49- Physical Health Effects

32:52- God’s Plan for His Children

37:01- Desire To Relate in Healthy Ways

39:45- What Does It Mean To Be All In the Gospel of Jesus Christ?

Morgan Jones 0:00

With the week of Valentine's Day upon us, this week's episode felt particularly important. It is widely believed that an understanding of adult attachment first explored by psychologist John Bowlby in the 1950s can help us enjoy lasting love. Brother Russell Osguthorpe has observed the importance of this attachment in professional as well as ecclesiastical responsibilities. And he is a firm believer that it is by increasing our capacity to give and receive love, that we can create healthy relationships with God and others.

Russell T. Osguthorpe has authored four books and more than 70 articles on religion and education. He holds a PhD in instructional psychology and has served as a professor and administrator at Brigham Young University. He has also served in a variety of Church callings, including Sunday School general president. He has conducted seminars in more than 25 countries and speaks several languages. He recently published a book titled Filled with His Love, which will be the topic of conversation today.

But before we get into our interview, I think it's worth mentioning that Brother Osguthorpe has opted to donate all of his royalties from the sales of this book to the "Lighthouse Sanctuary," a shelter in the Philippines for trafficked children. He hopes it will benefit children whose ability to attach in relationships in their lives has been negatively impacted by the decisions of others.

This is All In, an LDS Living podcast where we ask the question, what does it really mean to be all in the gospel of Jesus Christ? I'm Morgan Jones, and I am so honored to have Brother Russell Osguthorpe on the line with me today. Brother Osguthorpe thank you so much for being with me.

Russell Osguthorpe 1:50

Sure. Great to be with you.

Morgan Jones 1:53

Well, I have been reading your book, and am so excited to talk about it today. Brother Osguthrope has a book coming out called, Filled with His Love. And it's all about a topic that I think is fascinating whether you are a member of the Church or not, which is, attachment.

And you specifically talk about attachment to God and attachment to those around us. But before we get into this, there may be some listening, I think, that may have an adverse reaction–if they're not familiar with attachment theory, they may have a little bit of an adverse reaction to the word attached or attachment. I think a lot of people are like, well, I want to feel connected, but I don't want to feel attached. What would you say, Brother Osguthorpe to those people?

Russell Osguthorpe 2:41

It's a good question. Some people have said, "Why didn't you just use the word 'relationships,' or 'connections,' you know, rather than 'attachments' in the book?" But actually, the more I thought about this word, the more powerful it became to me.

So you know, we're connected with people in our professional networks. We're connected with people on social media, but a lot of those people, we actually don't know very well. We have connections with them, but we're certainly not attached to them, because we really don't know them that well.

But the close people we have in our family, the close ones we have with friends, the loved ones we have, those I think the word 'attachment' is so much stronger and helps us kind of set a higher goal for our relationships.

I just ran across the other day–in fact, just yesterday–I was reading a little bit about Prophet Joseph, and he had this quote, we've all heard the quote where he says, "Friendship is a basic principle of the gospel." But he followed that up–but I hadn't seen this before–he followed it up with, "Friendship is like Brother Turley in his blacksmith shop, welding iron to iron. It unites the human family with its happy influence."

I thought, wow, iron to iron, these two pieces of iron being welded together. That's attachment, I like the metaphor. And he was using it for friendship, but we could use it obviously for being attached to God, being attached to our family members.

The scriptures also–they say, this is in the New Testament, and I've always wondered exactly what this meant and it's coming more clear to me now, it says that we should know as we are known. Hmm, what does that mean to know as we are known? I think what it means is, we need to come to know God as He knows us. And we need to come to know his children as he knows his children. When we do that, we will be attached and it's stronger than a relationship or a connection.

Morgan Jones 4:48

I love that. Okay, so for those who are not familiar with attachment theory, can you explain to those listening what that is and maybe a little bit of background on the different types of attachment?

Russell Osguthorpe 5:03

Sure, attachment theory was kind of created in the mid last century in the 1950s 60s, in England by some developmental psychology people who were looking at the relationship between young children–very young children–and their parents. And they noticed how some children had an aversion to their parents at times, and some children had this very anxious attachment to their parents, they couldn't stand being without them for two seconds.

They started looking at these patterns, and that's what kind of gave rise to attachment theory. Only recently have we looked more at how attachment theory affects–and attachment styles–affect adult relationships. Those early pioneers in the theory did not really think about that very much. But more and more people are thinking about that.

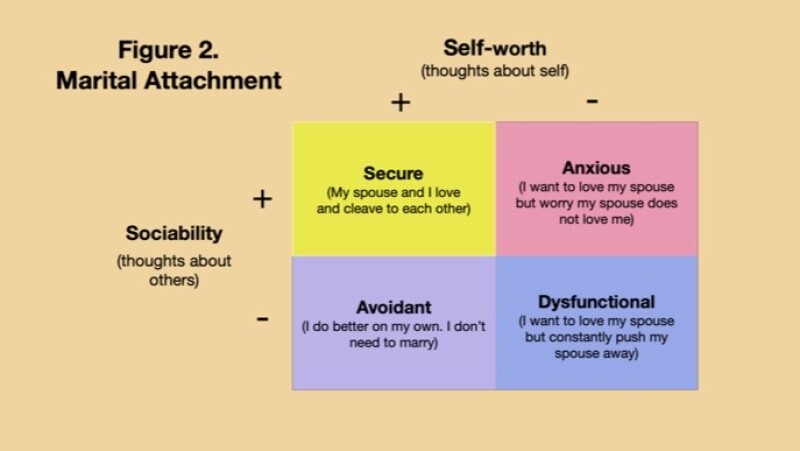

And also attachment to God. There are a large number of–a large number of articles now and books on what it means to have attachment with God and when we have attachment troubles with God. So if we had a video I would show this chart that I've got that helps me at least understand attachment theory.

So along the–we have four boxes, and along the top of the box, we have a thing called self-worth. In other words, how do we feel about ourselves. On the right side we have negative feelings on the left side we have positive feelings about ourselves.

On the left side of the four boxes is called, "Thoughts about Others–Sociability." In other words, top thing is how do we feel about ourselves and the left side is how do we feel about others.

So in this positive, self-worth box, and positive sociability box, we have what we call secure attachments. These are safe, secure–we feel safe in the presence of our caretaker of our parent, of our spouse, whoever it is, we have this kind of secure, enduring attachment. So I paraphrase it, "I love my parents, and my parents love me." That's secure, you feel loved, and you're able to love them.

Now in the right, top box, where we have negative self-worth but we have positive sociability, we have positive feelings toward others, but we're very anxious. So it's called anxious or preoccupied, we're always wanting more, we always want to be closer to the person. So when someone doesn't text us, we feel left out, we feel forgotten. And we have this anxious kind of feeling that we need more closeness to the person. So that's anxious attachment.

In the left bottom box is called avoidant style. Now in the avoidant style, that person says, "You know, I feel confident myself. I have positive self-worth. But I really, really do not need other people," or "I really maybe don't even need God." So that's the extreme avoidant.

In the right bottom box is kind of a mix of the anxious and avoidant and so I call that dysfunctional. It's, it's really one of the toughest boxes to be in. It's kind of like, "I wish my parents loved me, but I feel I need to protect myself from them, because sometimes maybe they have damaged me, ignored me, abused me or whatever it might be." And so they've got this anxious and avoidant style going on, which causes a lot of emotional trouble and relationship problems.

So, I don't know, does that–does that help you?

Morgan Jones 8:42

Yeah, no, that's awesome. That's super helpful. And we'll include that chart, if it's okay with you, in our show notes, or maybe share it on Instagram so that people can visualize what you're talking about. But I think that's a great explanation. So before we get too far into this, I think it might be important to talk about how . . . to kind of give people some hope, because they may be listening and be like, "Oh, I feel like I identify with this," but your message in the book is that these things can change.

Specifically, you write, "The good news is that anxious and avoidant feelings can be overcome. Particularly as one comes to rely on the mercy and grace of the Savior's Atonement. Anxiety can be changed into feelings of security. Avoidance can be replaced by enduring love for God and for others."

So maybe just give a little bit of a message before we get too far into this–a little bit of a message of hope for those listening about what this might–how this might happen.

Russell Osguthorpe 9:52

Yeah, I remember when I described this chart to one person, he said, "Okay, definitely I am anxious. I have an anxious attachment style and that's just the way it is." And–but, of course, we all have some of that in us. Some of the anxious part and some of the avoidant part. But the research that psychologists have done recently, I think, is very hopeful.

Because what it says basically is, if a person wants to change or improve their attachment style, if they want to develop a secure attachment style and right now they have an anxious one or an avoidant one, they can do that through help, through therapy, through–well, in many ways it's what I tried to do in part three of the book.

I give 20 suggestions, I call them recommendations, whatever we might call them, 20 ways that we can improve our attachment style or ability to love and be loved. And so, right now, my kids convinced me I needed to do a podcast myself. And so I've done a podcast called filters is love, where I am just going through those 20 ways and saying, "Okay, briefly," I take 10 minutes and just say, "Okay, here's what it means to get more stillness in our life," or "Here's what it means to make our own emotions." Or "Here's what it means to use candor, and kindness when we communicate."

I just go through some of those things quickly and help people see, okay, I could improve my communication style. I could improve the amount of stillness I have in my life, because right now my life is hectic and distracting and difficult. So, I don't know, is that helpful?

Morgan Jones 11:36

Yeah, no, that's great. I think . . . I think also, correct me if I'm wrong, but it seems like circumstance can kind of change your attachment as well. So recognizing that, like there are different factors at play. And it's not just "Oh, I'm broken."

Russell Osguthorpe 11:53

Exactly. Now, as I say, we all have, perhaps times in our lives when we have difficulty–when we don't feel like being around people, we're kind of avoidant. We all have times in our lives when we worry about the other person's love for us, that anxiety comes in. And that–when that anxiety comes in or that avoidance comes in, it can hurt the relationship, but really often, it just can be momentary. And we can get past that. And we can–I think the important thing about attachment theory is it helps us say, "Okay, wait a minute, who am I? How do I relate to other people?"

So that's, I think, the main benefit of my book, I can say, "Okay, this is when I need to kind of change the way I relate to other people because I can do that if I just kind of become conscious of it."

Morgan Jones 12:42

Right.

Okay. So, Brother Osguthrope you are the former Sunday School general president. You–from what I understand, you developed this interest in this topic because of your Church service. So can you talk to me a little bit about how you initially became interested in attachment theory?

Russell Osguthorpe 13:03

Sure, I had so many experiences, it seemed to me that–I was a stake president of a young married stake, also a mission president before serving in the Sunday School and in all of these counseling experiences, it seemed to me that everyone was coming to me with relationship problems.

Yes, some came to me with other kinds of problems, but in one sense, they mostly boiled down to relationship problems. Even addiction problems often have their root in attachment problems. People turn to substance abuse, because they don't feel loved often.

So, I mean, when they were coming to me with marital difficulties, or with addiction problems, I say, "Okay, let's talk about how you relate to other people." And I didn't have the, the tools–in a sense–at that time, because I wasn't aware of attachment theory back then. This was quite a while ago when I was a stake president.

But now I look back on it. And I say, "Okay, all of these people that were coming to me, particularly those who were contemplating divorce, were all having difficulty with attachment problems that they had not recognized and didn't understand in themselves." And they needed to do that before they could move on I think.

Morgan Jones 14:17

I think that's spot on and I think that it's so true that relationships, I think, are so much at the root of our well-being and you have a chapter in the book where you talk about how this can even relate to our physical health and vice versa, meaning, you know, if you don't have a secure attachment, I think it can have an effect on your physical health and your physical health can have an effect on your ability to attach. Well, that's one of the things that you talk about to build attachment.

But let's–you mentioned that this started because researchers were looking at the way that a child was raised and how that affected their ability to attach, how does the way that a child is . . . or the child's relationship with its mother, how does that impact their attachment?

Russell Osguthorpe 15:12

So if the listener can look at that diagram that maybe you might post on Instagram or something, if a child feels cared for, protected, and safe–they call it safe haven and security. So this, if they feel like in their home, they're in a safe haven, in other words, they don't have to be afraid of their parent. And they have–they call it a secure base, I love this term because it's kind of like a base to jump off of.

And so someone who feels a secure base, a child that feels that says, "Oh, I can create, I can play–I can try new things. I can play in new ways. I can interact with people in new ways, I can meet new people, new kids, and everything and feel comfortable, because I have a secure base," the parent has made them feel secure enough to launch out themselves later. And this really has effects for adults.

I worry that so many people don't launch out, they don't become creative as they could be, they don't use their imagination as much as they could, because they never really could feel a secure base, they never felt secure in themselves. And it has a lot to do with this perception of themselves.

When people say, "Oh, I just can't do that, I'm not good at that." They don't have a secure base, you say, "Well, maybe you're not good at that right now, but you could be good at that. And maybe we can help you be good at that, let's help you be good at that." And then you can develop this feeling that you can create and achieve more than you thought in the other boxes. So the anxious one is where the parent is kind of on again off again. So either abuse or neglect, some kind of mix of that can go on there.

In the avoidant one. In the extreme case, this is where abuse comes in. So if a child feels–is abused in some way, verbally, physically, sexually, in whatever way, then that child says, "Okay, I can't trust the adults in my life. I can't trust people to do what they really should do. This person should be loving me, and this person's actually hurting me." And so that is kind of the avoidant person has some of that probably in their background if they really are very, very avoidant.

And the anxious person has this other thing where they can't, they want the parent to love them, but the parent keeps pulling away at times, and they can't figure out why. And this is, you know, some parents just have difficulty really developing attachment with their own children. And so they need help in the early going, as they're raising their kids. So is that helpful to kind of give a picture of that?

Morgan Jones 18:01

That's super helpful. And then another thing just to kind of lay the groundwork. So like I said, the basis of your book is not only our attachment to those around us, but also our attachment to God. And you talk about how our attachment to God also affects the way that we're able to attach to others. And I found this really interesting.

I participated in a focus group that the Church was doing a few years ago, and one of the biggest things that they talked about was, "How does your–what is your relationship with your father like?" And then, "What is your relationship to your Heavenly Father like?" So how would you say that that attachment to God also affects the way that we attach to others or maybe even vice versa?

Russell Osguthorpe 18:46

So it's really well documented that people who have a negative relationship, abusive or neglectful relationship with their father have a difficult time attaching to God. I tell a little story in the book where one of my friends was working at a center for children with emotional problems. And he said, "I thought well, I'm just going to teach them the 'I am a Child of God' song and talk about how we're all children of God.'" And he did that.

And the therapists that was there with him said–well, he said, they didn't seem to respond very well. And he said, "Okay, wait a minute." He said, "All of these kids in here–virtually all of them–have been abused by a father." You come in and say, "You should think really great things about Father in heaven they can't do that. It's very hard right now. They have to overcome lots of baggage in order to be able to do that."

So that happens, these are extreme cases, but they kind of help us understand a little bit, the more mild cases as well.

Morgan Jones 19:51

Absolutely. Okay. So you kind of get into the book and we'll talk a little bit about some of the specific things, now that we've kind of given people some background. You write that nothing can create attachments as strong and enduring as making and keeping covenants with God. Why would you say that that is, Brother Osguthorpe?

Russell Osguthorpe 20:18

I really like that question, Morgan. That gets to the heart of what we're doing in this–trying to do in this book to me. Covenants obviously bind us to God, we are called "Children of the Covenant," we make promises to him, He makes promises to us. And we don't make such promises or covenants to people we barely know. We might have 300 friends on LinkedIn, but that doesn't mean that we make covenants and promises with these people, right?

This is a special relationship that we have with God, we have covenanted to be His covenant children. So making a covenant is just the beginning. Every time we keep that covenant, it is in the keeping of the covenant, that we deepen that relationship. That we help that attachment become stronger. And that's what I think is beautiful about temple worship.

The Lord didn't say, "Go to the temple sometime in your life, and then enjoy the rest of your life." He didn't say that. He said, "Go to the temple, and make those covenants and then go back again, and make the covenants that you made for yourself, make those same covenants for others. And you'll be reminded of the importance of keeping those covenants." And when we keep those covenants, He knows this, the Lord knows this, then, basically at that point, that's when He can fill us with His love. When we are His children, totally committed to Him, then we can be filled with the love that He has for us, which is an infinite love.

Morgan Jones 22:04

I love that so much. And we'll talk a little bit later you have this quote that I really love that kind of outlines the fact that God has–everything in God's plan is kind of centered around this idea that commandments, covenants, all of these things are to help us love and be filled with His love. And I just think that idea is so beautiful.

I really loved another thing that you talk about. So we've talked about, you know, relationships with parents, and obviously, like there's marital relationships, but you also wrote about siblings, which I found to be really interesting, as the sister of five brothers and sisters. You wrote, "Parent, child, and marriage relationships are crucial to our well being in mortality and beyond. But all family relationships are important. Consider one's relationship with siblings. These brother and sister attachments can last longer than any other familial relationship. On average, our parents will die 25 years before we do," which is something I had not considered, "But our siblings will be on Earth after our parents have left us. Given the potentially long time siblings inhabit this earth together, we may spend surprisingly little time thinking about the impact of these relationships on our own life."

You then say that while sibling relationships can be some of our closest in this life, they can also be our most frustrating. Why would you say that that is?

Russell Osguthorpe 23:39

I mean, one reason is because we know we should love our siblings, we know we should be close to them, we know we should kind of want to spend time with them all the time, even when we're adults, and sometimes if we don't feel that way, it's frustrating for us.

Psychologists actually have done lots of research on sibling relationships. I just barely touched on it in the book. But one thing they found is that siblings have less in common usually with each other than they do with their friends. And what they're saying is even though the siblings grew up in the same household, and they share some of the same DNA, they may not have a whole lot in common with each other as adults, because their paths sometimes go different ways, whereas their friendships were all by choice. They chose who to be friends with. Siblings all just kind of came in this family together.

So I think from a gospel standpoint, though, we want to say to ourselves, okay, if my sibling relationship is not what I want it to be, then I need to do what I can to see what I can do to make that relationship better than it is, because it can be a very rewarding relationship attachment, even if we don't have a ton in common.

Now, I read a book while I was writing this book, I read a book called Fault Lines. Very, very well done book by a psychologist at Cornell who did research on family estrangement. And one of the things he found, which was kind of disturbing, disappointing to me, he said, "Okay, about one in four people in the United States is currently"–this is one in four US adults–"Is currently estranged from at least one family member."

How did he define estrangement? He said, "Estrangement in this case means at least two years without saying a word to each other. No communication."

Then he went on even further, he said "Okay, even more troubling is that 40% of adults in America have experienced this kind of estrangement at some point in their lives." So many of them have overcome it, because only 25% are experiencing it now. So obviously, it can be overcome.

He spends his whole book talking about reconciliation, and kind of putting past problems away, and coming to reconcile with each other. If two siblings have become really estranged from each other, because they don't like each other, then they can overcome that through processes of reconciliation. And he goes into that in this book, very nice book.

So this is why sibling relationships can be so fascinating, because in some cases, people become literally detached from each other. And we know in the gospel sense, we don't want that to happen. We want to find ways to love one another, particularly in our families.

Morgan Jones 26:52

Well, and I think that goes back to the topic of covenants, right? If we understand covenants, and that we are sealed together as families, we want to do whatever we can to preserve those relationships, recognizing that there's power in covenants. You also talk about the effect that–so this is kind of moving into the later part of the book–you talk about the effect that giving specific praise can have on our ability to attach to those around us. Why would you say that words are so important?

Russell Osguthorpe 27:29

I've always loved that quote by Elder Maxwell, where he said, "We need to give each other more deserved specific praise." We don't want to praise each other if it's not deserved. We don't want to tell a child, "Oh, you just read that correct word," if he didn't read the word correctly. But we want to give more deserved specific praise, and why?

Because words–it's a really great question, Morgan, because words are at the heart of relationships and attachments are exchanging words. I used to–when I was Stake president, I would ask couples who were struggling a little bit, I would say, "Tell me about your communication patterns? Is there ever any harshness?"

And sometimes they would say, "Well, what do you mean harshness?" And I'd say, "I mean, are you ever kind of verbally attacking each other?" And they'd say, "Well, you know, everybody fights." And I'd say, "Well, no, everybody doesn't have to fight to come to agreement. You can come to agreement over a disagreement by calm and measured communication. Kind communication, you don't have to attack each other."

And so words can hurt people. The scriptures teach us, you know, it says, "It is said that thou shalt not kill"–this is in the New Testament–and it's saying, "Thou shalt not kill," we all know this commandment, but then after that, he follows it and say, "Well, I say unto you, even now that you should not use the word Raca." In other words, you should not use verbal attacks on each other either.

I had a friend, this fellow was a friend back East. Not a member of the church, but I thought it was a great insight. He said, "When we give advice that is not sought or not wanted, it is an act"–he says it can be–"An act of violence." So when someone doesn't want the thing that we're saying, and we keep forcing it on them and pushing it on them, we're kind of hurting them in some ways. And when we attack verbally, I think we literally kill something inside the person. Sometimes people say after these verbal fights, "I feel like something died inside of me after I got so attacked verbally."

So these are things we do not want in secure attachments. They are things we don't want in enduring eternal relationships. And so we have to find ways to change those patterns of communication so that we give life to each other. The–I thought the other day of one of my favorite greetings. When I, when I was a young missionary, I went to Tahiti. The way they say hello is, "Ia Orona," which means literally, "That you might live," or "Life to you." "I'm giving life to you when I say, 'Hello.'" That's what we want to do with each other. We want to give life. We don't want to kill something inside somebody.

Morgan Jones 30:37

Yeah, no, I think that that is profound. What effect can not feeling–I mentioned this earlier, you talk about physical health, and it's tied to our attachments, but what effect cannot feeling secure in our attachments to those closest to us have on our physical health?

Russell Osguthorpe 30:57

Again, you know, medical science has documented these effects very . . . thoroughly, I might say. And when I talk about stress, you know, when we don't have a good relationship a secure attachment, then we have stress. And that stress, of course, leads to anxiety, or at least to the avoidance thing, where we just say, "I give up, I'm not going to relate to people anymore."

But you know, when someone feels this stress–I don't, all stress is not bad. Stress can be productive for us if we learn how to deal with it, but relationship stress, which is kind of a constant battering of our emotional equipment, really, that's hard to deal with. That has to be fixed. We can't go on day after day, feeling that our spouse hates us, wants to get back at us, is angry at us–all those things.

And so, in these cases, we need to figure out, you know, what can we do to help this relationship get better? Because our physical health, it's documented that it raises blood pressure, it raises the risk of heart disease, it raises the risk of digestive problems, you name it, all parts of our body are affected by our brain. And when our brain is not healthy and happy, in a sense, the rest of our body does not do well. And we've all experienced that. Sometimes we don't recognize it, and we can't put our finger on it. But our physical problem is so often due to our emotional wellness.

Morgan Jones 32:36

I 100% agree with that. I think that's–I think sometimes we underestimate the ability of our body to tell us how we're doing emotionally. At the end of your book you write, "Relationships are fluid and alive. They need to be nurtured and protected like all living things, otherwise they can wither and even die. God's covenant children, by definition, have committed themselves to form safe, secure, enduring attachments. He gave us commandments, covenants, temples, scriptures and living prophets to help us achieve this very aim. He knew that success would come only with our commitment, love, faith and action. The Savior knew that exaltation is a family matter, that no one could be exalted alone. That is precisely why He came to earth, lived among mere mortals, and demonstrated by his teachings and his life, how essential it is to be filled with His love."

I wondered Brother Oscuthorpe as you've been working on this book, what it taught you–what all that you've studied and learned–taught you about God's plan for his children?

Russell Osguthorpe 33:51

I also love that question, because I've learned a lot. And it's been in one way for me a kind of sacred kind of learning. Because learning that leads us closer to God is a sacred act, it's a sacred experience. And I write to learn, and so I uncovered so many studies, philosophical writings, all kinds of things that led me to come to a greater understanding of just how important it is to love God and love His children.

In the very beginning of the book–and I'm not sure how I found this particular quote, but this is a powerful quote, this is Mother Teresa. And the short part of the quote is, "There are many in the world who are dying for a piece of bread. But there are many more dying for a little more love," right. "There are many in the world who are dying for a piece of bread, but there are many more dying for a little love." So you can erase that first part, take the good part.

Now we picture Mother Teresa working with the most impoverished, the most hunger ridden population ever in the depths of Calcutta in India. This is amazing that she said, "Yeah, I realize there are lots with disease, there are lots with hunger, but the number one problem–over all else–is they don't have enough love."

When I was in the Sunday school, presidency we would train all over the world. So we'd have these large congregations like 800 people in a stake center. And I would look out at this group and I would say, "Raise your hand if you are right now receiving too much love." And nobody would raise their hand I said, you know, it's kind of interesting that love cannot, we cannot receive too much love. I mean, really, the pure love of Christ the pure, really good love, I'm not talking about smothering, ineffective love. I'm talking about love in the truest sense, we can all use a little more.

And that's why Mother Teresa said, "There are many more dying for a little love." For those who are love deprived, there is no question in my mind that that love deprivation leads to emotional, physical, really disastrous problems for them. So we all need to find ways to love one another more. And that means to bring that love that God fills us with when we attach ourselves to Him. When we get close to Him, the closer we get to Him, then the closer we want to be with His children, and to invite all of them with inclusion, and acceptance and total, pure love of Christ as it says in Moroni.

Morgan Jones 36:58

So well said thank you. You also write that, "Love changes us. But for the change to occur, we need to accept the love that comes to us from God and from others and then seek to share that love with as many as possible." And then later you say, "But we first need to want to change. Desire is essential, only then can we begin to relate to others in healthier ways. When we choose to change our capacity to give love to others increases, it is not a one way stream. Love always needs to flow in both directions."

Talk to me a little bit about the transformative power developing a secure attachment can have on a relationship and why creating more secure attachments, no matter, you know, where we're at with this, is something that we should all strive for.

Russell Osguthorpe 37:50

Yeah, it's kind of like when we come to the end of life it's really all that matters, our relationships. It doesn't matter how much money we made, or what kind of recognition we got from other people, but we want to make sure that people know that we love them. And we want to feel their love, this is the ultimate thing in life.

And so we all have some avoidance or anxiety kinds of reactions at times in our relationships. And overcoming those is possible, you know, as it says, if we want to, a lot of research showed–they looked at all these people with attachment disorders. And they kind of measured how they did with therapy, well, they had to want the therapy, they had to want to get better or they didn't get better.

So people, if change is going to happen inside us, we first got to have that desire to do it. And so I think of the old saying too that says you need to work out your own salvation, you say, well, maybe I can work out a little bit of my own salvation, but I can't work out exaltation. President Nelson has been very clear exaltation is a family matter. So we have to live together in love. This is the most important thing we do when we come to earth, learning to live together in love so that we can have that kind of happiness, joy in relationship through mortality and then on through eternal life.

Morgan Jones 39:34

Thank you so much. My last question for you Brother Osguthorpe, and first of all, thank you so much for sharing these things with us and for all the work that you've put into to this book. My last question for you is, what does it mean to you to be all in the gospel of Jesus Christ?

Russell Osguthorpe 39:52

I like this question also. And I like that you ask it to every one of your participants. When I think about it, I think about oneness. You know, the Restoration has taught us that separate beings, like God the Father and God the Son and the Holy Ghost, they are separate beings–can be one. Now obviously we know that they do not meld into one being, but they are separate beings, and as the Savior when He prayed in Gethsemane, the intercessory prayer in John 17, when He said, that, "I can be in thee, I in thee, and thou in me, that we may be made perfect. That all may be made perfect in one."

So, for me being all in means, I want to do all I can to be one with the Savior, one with my family, one with others. Because at first the Savior was praying for His apostles that, "They might be one as we are Father, I in them and thou in me that all may be one." But then He prays for that, "All those that thou has given me," in other words–all of us, that we can come to this oneness.

When that happens, and we have real unity, not just in ourselves, but with each other and in societies, of course, we're just so far away from that right now. We have a lot of divisive kinds of things going on. But the Gospel says to us, the Lord says to us, "We want you to be one. We want you to be united in love." And so to be all in, that's what it means to me.

Morgan Jones 41:43

Thank you so much. Brother Osguthorpe it's been such a joy to be with you. Thank you for your time.

Russell Osguthorpe 41:49

You bet. Thank you, Morgan.

Morgan Jones 41:53

We are so grateful to brother Russell T. Osguthorpe for joining us on today's episode. You can find Brother Osguthorpe's book, Filled with His Love on Deseretbook.com now. Big thanks to Derek Campbell of Mix at Six studios for his help with this episode and thank you so much for listening. Happy Valentine's Day.