Editor’s note: This article was the cover story of the March/April 2022 issue of LDS Living magazine.

The sun was not yet up on January 17, 1989, when 24-year-old Nnamdi Okonkwo arrived at the American embassy in Lagos, Nigeria. A flight to New York City would be departing at 7:00 p.m., and this was his last chance to be on it.

His journey to the gates of the embassy hadn’t been easy. Only a few days earlier, his request for a visa to America had been flatly denied due to expired paperwork at a different office. Government workers had even stamped the back of his passport to indicate that he would have to wait six months to reapply. But Nnamdi didn’t have six months. The nonrefundable plane ticket he’d bought in an act of faith was scheduled to leave in a matter of days. This seemingly journey-ending setback should have devastated him, but Nnamdi wasn’t ready to give up quite yet. Instead, he crammed his 6-foot-9 frame into an overnight bus and rode 500 miles to the American embassy in Lagos, arriving on January 16, hoping officials there would grant him a visa—only to find the office closed for the day.

He approached the embassy gates again the next morning, keenly aware that his flight would leave in a matter of hours. As he waited in line, at the forefront of Nnamdi’s mind was a story in Genesis 19 where God temporarily blinds the eyes of wicked men to protect a man named Lot. His prayer now was for God to offer similar aid within the embassy.

“I would ask Him to blind the eyes of anyone that would examine my documents at the embassy so that they would not see the expired dates, nor the stamp of rejection on my passport,” Nnamdi would later tell Brigham Young University–Hawaii students during a devotional. “Armed with the same faith as Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, I went back to the embassy with the expired documents. It was reckless and foolhardy, but I didn’t care!”

The plan never should have worked, but it did.

Nnamdi walked out of the embassy with a United States visa, a document that would prove to be his ticket to more than just American soil. He was now one step closer to discovering two very important things: the restored gospel of Jesus Christ and the calling God would give him to bear testimony through art.

Little could he have imagined as his plane touched down in New York that a permanent installation of his art would one day grace a street corner in that very city, emanating calm to hundreds of passersby each day. Or that a gallery in Washington, DC, would proudly display his art, or that a larger-than-life piece would gladden hearts halfway around the world in Changsha, China.

Only God knew then the contributions this young man from Enugu, Nigeria, would make in expanding the perspectives of Latter-day Saints and so many more through art.

Yes, God’s intervention in Nnamdi Okonkwo’s flight to the US was only the beginning.

On to Hawaii

Nnamdi’s plane ticket may have been to New York, but that wasn’t his final destination. He was heading to the island of Oahu, home of BYU–Hawaii: a school Nnamdi hadn’t heard of before being recruited there but which would serve as an answer to prayer in more ways than he thought.

During his last six years in Nigeria, Nnamdi worked toward one goal: learning to play basketball and getting recruited by an American university. He felt he was running out of options in his home country. At his mother’s insistence, he had pursued his lifelong love of art and graduated with a degree in painting from a college in Nigeria. But he longed for opportunities that he believed were possible only in the US and saw a basketball scholarship as his way to get there.

During those hard years of working for a scholarship, Nnamdi had pleaded with God for help. Faith had always come naturally to him, largely due to his mother, a deeply religious woman who made God a part of her family’s daily lives. At first, Nnamdi’s prayers had been petitions for the financial success he wanted for his family. His father had died when Nnamdi was only 12 years old, and as the eldest son, he had responsibilities to provide for the family. He wanted a scholarship for the sake of his beloved mother and brothers as much as he wanted it for himself.

But as he prayed one night in a moment of great frustration, Nnamdi had an impression that perhaps a spiritual future awaited him in the US as well.

“Please, God,” he later recorded was his prayer, “send me to a college where I will not only get to play basketball and live the American dream but please send me to a place where I will also have the opportunity to learn more about You and draw closer to You so that I can serve You better.”

That new prayer imbued him with a confidence that carried him until God answered with a call from BYU–Hawaii.

It wasn’t long after Nnamdi’s arrival on the island that his friends and then the missionaries started teaching him the gospel. And yet, despite his prayer for an opportunity to draw closer to God, Nnamdi had some hesitations and didn’t want to join the Church at first.

“I felt terrible because in my mind I would be disowning my religion that has been wonderful to me, everything that my mother taught me,” Nnamdi says. “But the hardest thing for me to get over was the fact that Joseph Smith was a prophet. Even though I had a testimony that the Book of Mormon was the word of God, I just never imagined that there’s going to be a prophet named Joseph Smith. … And, of all places, in America? It just felt too made-up, too contrived.”

Nnamdi wrestled with his conflicted feelings for several months, all the while praying to know if the Church was true. Receiving confirmation from the Spirit that it was, he decided to put his hesitations aside and was baptized six months after arriving in Hawaii.

“Everything doesn’t have to make sense yet for you to let go of the knowledge you … already have,” Nnamdi says, reflecting on that decision. “God speaks to our hearts. [And] even if your father, your mother, [or] everyone is against it, you have to hold on to what you hear in your heart.”

Nnamdi has now been a member of the Church for over 30 years. Throughout that time, he’s seen how the courage to stay true to his heart isn’t just needed in matters of faith; it has also proved essential in matters of art.

Purpose in Clay

Prior to arriving at BYU–Hawaii, Nnamdi had earned a degree in painting. But despite his talent for the medium, he was hesitant to pursue it further, never feeling like “that was what I was born to do.” Now that he was in Hawaii he wanted to explore new mediums, so he signed up for a sculpting class. Just one day in, he was ready to lay his brushes aside.

“It was pretty dramatic. … I put my hand in clay that very first day and it just felt so natural, so good: like I’d finally found what I was sent here to do,” he says.

So the BYU–Hawaii athlete quickly declared his major in sculpture. One of his fellow students was LeRoy Transfield, a young man from New Zealand who had also come to BYU–Hawaii from humble beginnings. LeRoy remembers Nnamdi being rather quiet as he adjusted to the culture shock of moving to Hawaii, but that changed as time passed and the two became great friends.

That friendship continues to play an important role in the men’s lives today. Out of everyone in their class, LeRoy says he and Nnamdi are the only ones who have stayed committed to being studio artists. LeRoy describes being an artist as an “emotional roller coaster,” and the two college friends have leaned on each other for support during the highs and lows of the ride.

LeRoy has appreciated Nnamdi’s natural disposition for optimism—a trait he noticed about his friend after a mishap in Nnamdi’s college basketball days: He remembers Nnamdi tripping while going up for the final shot of a game and landing flat on his back as the buzzer went off.

“If that were me, I would’ve been walking around sheepishly on campus the next day,” LeRoy says with a laugh. But when LeRoy saw Nnamdi in the hallway, his friend was full of so much optimism, one would have thought he’d played a fantastic game.

“Nnamdi was always good at that ‘fake it till you make it’ type of thing,” LeRoy says. “Even back then he always had this positive attitude about him and his art, even if no one else did.”

As an accomplished artist himself, with sculptures featured at memorial parks across Utah, Martin’s Cove, the Polynesian Cultural Center, and the Newport Beach California Temple, LeRoy has an eye to appreciate the details of Nnamdi’s work.

“From a sculptor’s point of view, I like the way he uses mass to present his ideas. … I really admire him for wanting to get more big pieces out there. And he’s very particular about his patina, which I think really adds to the piece,” LeRoy says, referring to the way Nnamdi applies chemicals to a sculpture to create the desired aged finish.

Beyond technique, LeRoy admires how Nnamdi has stayed true to himself with each piece. “When I look at them, I can see Nnamdi. I can see his African heritage. … [He’s] not trying to pretend to be something he’s not,” he says. “He is very distinct, and that’s what makes him unique and collectible.”

After graduation, Nnamdi left Hawaii and went to Brigham Young University in Provo for a master’s program in sculpture. It was there that he began to more clearly understand God’s will for his art: a medium for relaying messages of peace, love, family, joy, and belonging—a way to help remind people of all that is beautiful about God and humanity.

But that wasn’t all that awaited Nnamdi in Provo. There, he would also meet the woman who would become his unfailing support and who would fervently declare, “Over my dead body!” when the pressures of life tempted him to give up.

Finding Deidra

While living in Hawaii, Nnamdi was devastated when a girlfriend he wanted to marry ended the relationship. But in hindsight, he can see how that tough breakup, and other failed relationships, were necessary because he was meant to be with Deidra.

“When I look at all my broken hearts at BYU–Hawaii, I didn’t know that it was the good Lord trying to preserve me so that I can do what I’ve always wanted to be. It takes a most special person to be the wife of an artist,” he says. “I could never ever say what I’ve achieved in art without acknowledging that she was the one who really made it possible.”

Deidra didn’t come from an artistic background herself. Throughout her childhood in Idaho, she was always more drawn to technical things; she was pursuing a master’s degree in accounting at BYU when she met Nnamdi.

“We’re totally opposite. I use one side of the brain, and he definitely uses the other side,” Deidra says. “[But] I think that’s what attracted us to each other: we could see our weaknesses and liked that the other person had those strengths.”

Deidra remembers Nnamdi being popular in Provo. His dynamic personality drew people to him, including many interested women. But Deidra found a way to spend some extra time with him.

“I noticed that he was going to the rest home every day. He felt like his mother, who was in Nigeria, needed someone to care for her because he wasn’t there. So if he was caring for someone else, then Heavenly Father would take care of his mother,” she says. “I knew the rest home was far away and he didn’t have a car, so I offered to give him a ride. I fell in love with him there; the way he interacted with the older people, finding out about them and spending time with them—he just loves people.”

It didn’t take long for Deidra to know that Nnamdi was the man God wanted her to marry. Nor did it take long for her to see the divine nature of his work as an artist.

“I never doubted. It was just so true. I can’t even explain it in any other way,” she says. “I knew so strongly that he was the person I was supposed to marry, and I believed so much in him and his calling as an artist.”

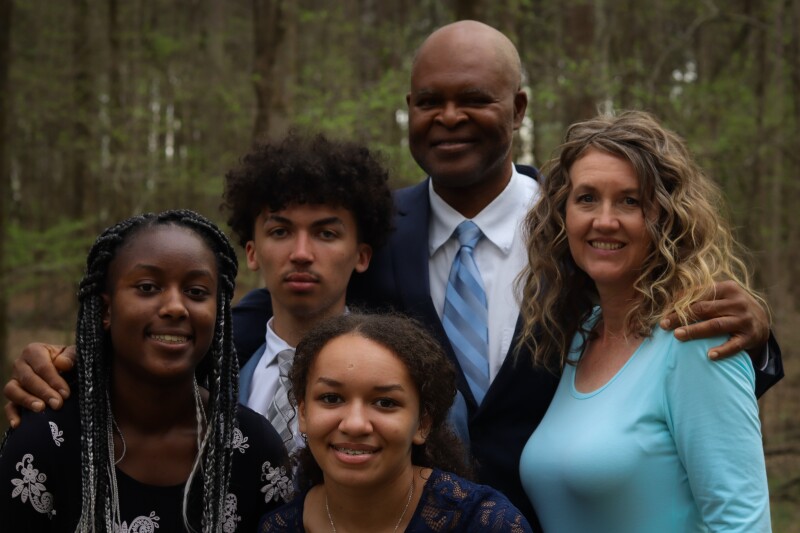

Faith over Sales

Deidra’s commitment to her husband’s calling proved essential during the difficult years of working up a clientele. The couple decided to move from Utah to Fayetteville, Georgia, in 2007. Deidra had left full-time employment to be at home with their three children, so Nnamdi became the sole breadwinner for the family.

Nearly every week, he was away from home as he drove to art shows around the country to market his work. Money was extremely tight. The family had suffered a significant financial loss in the sale of their Utah home, and then when the infamous market crash of 2008 hit, many of the galleries Nnamdi worked with went out of business.

“It was the perfect storm,” Deidra says, remembering those years as the hardest of their lives. “We wanted him to be successful, but it felt like it was a spiraling destruction.”

Under this pressure of providing for his family, Nnamdi told Deidra in desperation that he may need to look for a “real job.”

“Over my dead body!” was Deidra’s firm reply. “You were born to do this, and if it comes to that, I’ll be the one to get a job first.”

During those years of stress, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland’s conference talk “The First Great Commandment” became a turning point from fear to faith for Deidra and Nnamdi. In the message, Elder Holland pointed out how the original Apostles had shifted their focus back to fishing after the Savior died. When the resurrected Christ appeared to them, however, He reminded the Apostles that He could get all the fish He wanted—what He needed were true disciples. In Deidra and Nnamdi’s case, they felt their “fish” were art sales. They realized that in order to find joy in the present and success in the future, they were going to need to focus more on Christ and less on sales.

“Our fears and stresses were swept away in the pure knowledge that Christ would take the burden of providing for our temporal needs if we would rely solely on Him. It was life-changing!” Deidra says.

Nnamdi renewed his dedication to discipleship over “fishing,” but he did not give up on art. He continued to travel, earning enough to keep the family afloat.

“One of the reasons that I was able to stay in the game, even when it wasn’t clear to me that I had any talent, was because I felt like God was going to be with me, so there’s absolutely nothing that I couldn’t do,” Nnamdi says. “I think you get to a point where you then realize that it’s never going to come from your hard work: if it comes, it’s a gift from God.”

The gift did come. Through years of daily effort and faith, Nnamdi’s art is now featured in galleries and museums and as street installations across the country. His sculptures have won dozens of awards, including “best in show” at art festivals from New York to Texas to Illinois. Recently he won “best of sculpture” at the 2021 Red Dot Miami, a show held as part of Miami Art Week, which some consider to be America’s foremost modern art fair that attracts top galleries, artists, and collectors from around the world.

At just the right moments, Nnamdi connected with art enthusiasts who could pay well for large-scale commissions. He has since built up a dependable business with clients such as various city governments, the Church History Museum, Deseret Book, and a growing list of private collectors.

“Christ has our back. We’ve seen so much proof of that over these past 14 years that there’s no worry anymore,” Deidra says. “Nnamdi can completely, 100 percent, be an artist, and there’s no fear in that.”

The Language of Art

As Church History Museum curator, Laura Howe was drawn to Nnamdi’s art in part because of how it could touch Latter-day Saints around the world. To explain the spiritual importance of his art, she uses a comparison to languages: The Church values everyone being able to hear the gospel in their native language—so much so, in fact, that huge systems within the Church’s infrastructure, from missionary language training to extensive translation services, have been set up to make that happen.

Art is also a language, she says, and it communicates best when a viewer feels they can understand it. “Art is crucial in providing a space where people can work out who they are before God,” Howe says.

She explains that much of today’s Latter-day Saint art was homegrown: Historically, Saints gathered from around the world to Utah, and then over the years the Church “grew up” in a Western context that embraced a Western art style. Nnamdi, however, wasn’t raised speaking the language of Western art, so his work offers something new and needed as churches and members spread across the globe. For example, his sculptures of women feature full-figured, curvy forms—depictions that some cultures are unaccustomed to seeing. But as members consider different art forms, perspectives can expand.

“It becomes a question of: What language are we used to speaking, and are we willing to learn a different language? Can we see beauty in someone bearing their testimony in a different language?” Howe asks, adding, “Because if we can, that’s where the richness comes from.”

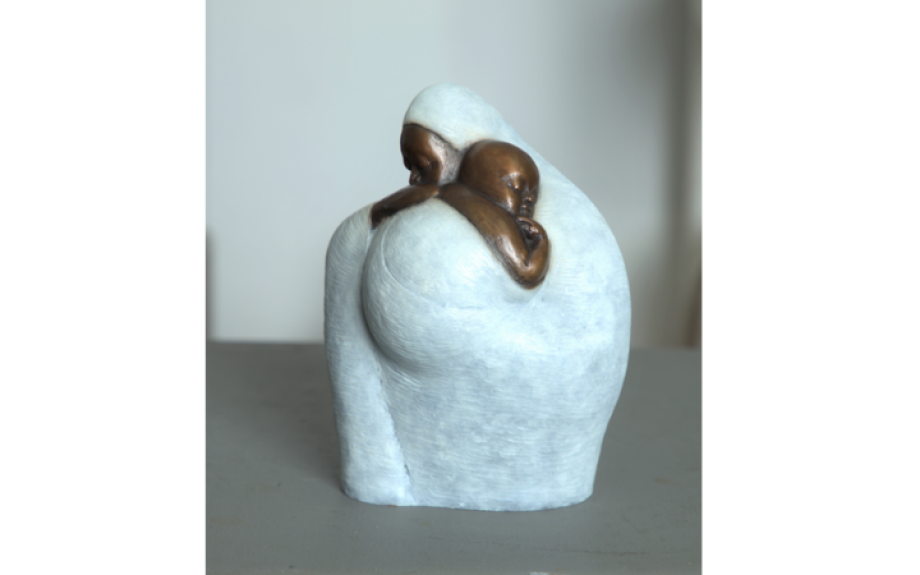

To add to the richness of the Church History Museum’s collection, it has acquired two pieces of Nnamdi’s work: The Family is a 36-inch bronze statue through which Nnamdi wanted to express the idea of unconditional love, drawing on the feelings he had bringing his first son home from the hospital. The second piece, Joy, is an 18½-inch statue of three women dancing together.

“It reflects Nnamdi’s joy and happiness in the gospel and wanting to share that,” Howe says. “Making sure that … all Latter-day Saints can see themselves as part of the collection has been important to the Church History Museum since the beginning, and Nnamdi’s work does that so beautifully.”

Expressing the Soul

Nnamdi sculpted mainly male figures while in Hawaii, drawing his inspiration from classical artists like Auguste Rodin and Michelangelo. But during graduate school, he shifted his focus to a style that felt truer to him and what God wanted him to do.

“There’s something subtle and beautiful that my heart is drawn to, [and] it’s not the outward power of a man; it is the inner strength of a person. The beauty of the soul is really what I’m interested in, and I wanted to express that in art,” Nnamdi said. “I realized that the female figure exemplifies more than the male figure that strength within—the beauty of the spirit within.”

Ever true to his heart, Nnamdi’s art has a religious focus, with themes such as God’s love, unity, and tranquility. His statues range in size from a few inches in height to larger-than-life works such as his 10-foot-tall, 15-foot-wide piece Jubilation, which is on display outdoors in Changsha, China. Nnamdi wanted the piece to express “that unrestrained joy is possible.” Another outdoor installation, the 8-foot-wide Friends, expresses “love and harmony” and sits on the corner of 120th Street and Fifth Avenue in New York City.

Nnamdi’s goal as a creator has always been to help people understand an aspect of God’s perfection and His love.

“When I arrive at something that I really love in the studio—man, you should see me dancing around by myself,” he says.

Nnamdi has learned to trust God and believe wholeheartedly in each person’s potential to meaningfully contribute to the world. And that’s a truth that continues to guide his art and his life.

“The magic that will happen in my art is when it isn’t coming from me; it’s coming from God. It is true that He requires me to work, to show up. But when that magic happens, it is going to be His hand doing it—not mine.”