Books, articles, and numerous Internet websites work to undermine faith in Joseph Smith’s first vision, but historically there have been just three main arguments against it. The minister to whom Joseph reported the event responded that there were no such things these days. More than a century later and in a literary style that masked her weakness in following the historical method, Fawn Brodie wrote that Joseph invented the vision years after he said it happened. A generation later, Wesley Walters charged Joseph with inventing revivalism when, Walters claimed, a lack of historical evidence proved that there was none and therefore there was no subsequent vision as a result. By now it has become a foregone conclusion for some that there are no such things as visions, that Joseph failed to mention his experience for years, and that he then gave conflicting accounts that failed to match historical facts. 1 But these three claims assume much more than they prove.

Each of the three arguments begins with the conclusion that the vision simply could not have happened as Joseph described it. Philosophers describe that kind of premise as a priori, a Latin term that describes knowledge that is, essentially, assumed. In other words, a priori knowledge does not rely on experience for verification. It is based on definitions, widely shared beliefs, and reason. Knowledge derived from experience is a posteriori. Joseph testified that he experienced a divine revelation and therefore knew. The epistemology in Joseph’s first vision accounts is a posteriori. The epistemology of Joseph’s vision critics is a priori. They know that what Joseph said happened could not have happened because all reasonable people know that such things do not happen.

“No Such Thing As Visions”

“Some few days after I had this vision,” Joseph reported, “I happened to be in the company with one of the Methodist preachers” who had contributed to the religious fervor. “I took occasion to give him an account of the vision,” Joseph continued, “I was greatly surprised at his behavior; he treated my communication not only lightly but with great contempt, saying it was all of the devil, that there were no such things as visions or revelations in these days; that all such things had ceased with the apostles, and that there never would be any more of them.”2

The preacher’s premises were all a priori, namely—

- Joseph’s story was of the devil.

- There were no such things as revelations in what Charles Dickens called the age of railways.

- Visions or revelations ceased with the apostles of Christ’s time.

- There would never be any more revelation.

No doubt this good fellow was sincere in each of these beliefs and striving as best he knew to prevent Joseph from becoming prey to fanaticism. But he did not know from experience the validity of any of the four premises he set forth as positive facts. All he knew a posteriori is that he himself had not had a vision or a revelation. On what basis, then, could this minister evaluate Joseph’s claims and make such sweeping statements?

An answer to that question lies in understanding the pressures on a Methodist minister in Joseph’s area in 1820. Joseph did not name the minister to whom he reported the vision. It’s not clear whether it was George Lane, whom Joseph’s brother William and Oliver Cowdery credited with awakening Joseph spiritually. Joseph could have heard or visited with Reverend Lane one or more times during his ministry in Joseph’s district in 1819 and the early 1820s, as he frequently visited the area from his home in Pennsylvania.3 There were local Methodist ministers, any one of whom Joseph could have told of his experience. All of them were conscious that Methodism was tending away from the kind of spiritual experiences Joseph described and toward a more respectable, reasonable religion. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, had worried that Methodists would multiply exponentially in number only to become “a dead sect, having the form of religion without the power.”4 And Methodism indeed grew abundantly because it took the claims of people like Joseph so seriously. Its preachers encouraged personal conversions that included intimate experiences with God, including visions and revelations. But then, as John Wesley had worried, Methodism became less welcoming to such manifestations.5 Just as Joseph was coming of age, many leaders of Methodism were becoming embarrassed by what respectable people regarded as its excesses. Methodism had risen to meet the needs of the many people who could not find a church that took their spiritual experiences seriously. But with its phenomenal growth came a shift from the margin to the mainstream.

Joseph was likely naïve about that shift, which is easier to see historically than it was at the time. Probably all Joseph knew is that he had caught a spark of Methodism and wanted to feel the same spiritual power as the persons he saw and heard at the meetings. He finally experienced that power in the woods, as so many Methodist converts, encouraged by their preachers, appeared to have done before him. So it was shocking to him when the minister reacted against what Joseph assumed would be welcome news.

As for the minister, he may have heard messages in Joseph’s story in ways that led him to respond negatively, especially if Joseph told the part about learning that religious professors spoke well of God but denied his power. No Methodist minister wanted to hear that the fear of his denomination’s founder had been realized. Yet by 1820 many Methodists were concerned about what had for nearly two hundred years been termed enthusiasm, “derived from Greek en theos, meaning to be filled with or inspired by a deity.”6 To be accused of enthusiasm in Joseph Smith’s world was not a compliment. It meant that one was perceived as mentally unstable and irrational. Methodists had tried to walk a fine line between valuing authentic spiritual experience, yet stopping well short of enthusiasm. It seems likely that young Joseph was not attuned to the sophisticated difference that had been worked out by Methodist theologians. He reported to the minister what he thought would be a highly valued experience that seemed to resemble the experiences of other sincere Christians. But his experience was received as an embarrassing example of enthusiasm and thus condemned.

1. Dan Vogel, Joseph Smith: The Making of a Prophet (Salt Lake City: Signature, 2004), xv.

2. See Joseph’s 1838 account in chapter 4.

3. The Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate (December 1834): 42; William Smith, William Smith on Mormonism (Lamoni, Iowa, 1883), 6; Deseret Evening News (Salt Lake City, Utah), 20 January 1894, 11; Larry C. Porter, “Reverend George Lane—Good ‘Gifts,’ Much ‘Grace,’ Marked ‘Usefulness,’” BYU Studies 9, no. 3 (Spring 1969): 321–40.

4. John Wesley, “Thoughts upon Methodism,” in The Methodist Societies: History, Nature, and Design, ed. Rupert E. Davies, in The Bicentennial Edition of the Works of John Wesley, ed. W. Reginald Ward and Richard P. Heitzenrater (Nashville, Tenn.: Abingdon, 1989), 9:527.

5. Christopher C. Jones, “The Power and Form of Godliness: Methodist Conversion Narratives and Joseph Smith’s First Vision,” Journal of Mormon History 37, no.2 (Spring 2011): 88–114; Jon Butler, Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990), 241. See John H. Wigger, Taking Heaven by Storm: Methodism and the Rise of Popular Christianity in America (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998), chapter entitled “Methodism Transformed.”

6. Ann Taves, Fits, Trances, & Visions: Experiencing Religion and Explaining Experience from Wesley to James (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999), 17.

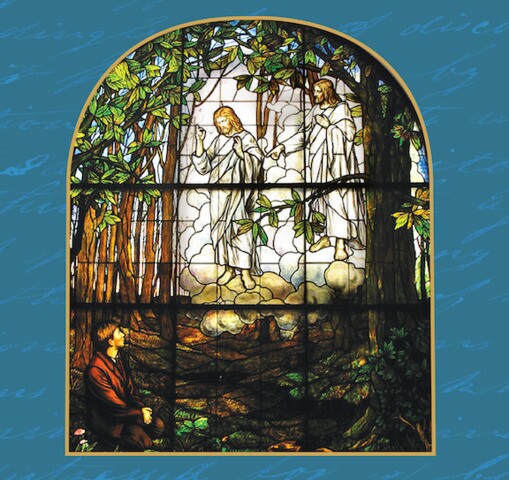

From the moment Joseph Smith first spoke of it, many have considered, examined, and questioned his account of God and Christ appearing to him in a grove of trees in upstate New York. As the only tangible evidence of the miraculous event, Joseph's recorded statements on the first vision are important today for both believers and critics: the truth of these records attests to Joseph's prophetic calling, the reality of the Restoration, and the assurance that God continues to speak to us today. Joseph Smith's First Vision is available now at Deseret Book and DeseretBook.com.