Before indoor plumbing, a man's strategy for slipping out of the house to meet up with his buddies for a night of mobbing and mayhem was to feign sickness and spend the night in the outhouse.

Once outside, the men pulled on hidden clothing and gathered at the brickyard on the outskirts of town.

That was the case on the night of March 24, 1832, when a mob of 60 men first attempted to castrate and poison the Prophet Joseph Smith before applying hot pine tar and covering him in feathers, said Susan Easton Black, an emeritus professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University.

"At Symonds Ryder's funeral (in 1870), his son Hartwell Ryder spoke of his father and said all these glowing things. Then he said, 'On the books of the Mormon Church out in Utah, it says that Symonds Ryder led the tarring and feathering of Joseph Smith,'" Black told her large audience packed into a room at the Wilkinson Student Center. "Hartwell, his son, then said, 'I well remember that night. My father was extremely ill and spent the night in the outhouse.'"

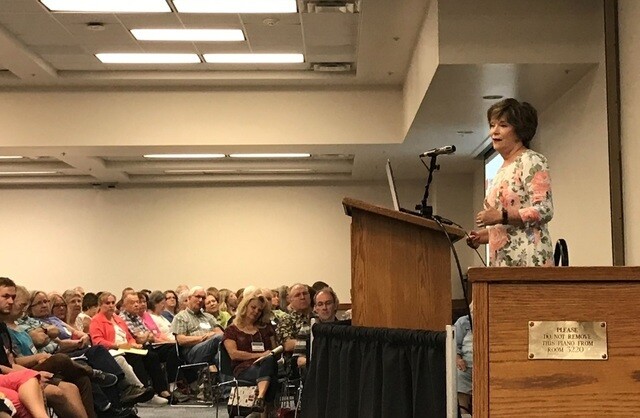

Black delivered her remarks, "A New Depth of Anger and Rage: The Tarring and Feathering of Joseph Smith," Monday as part of BYU Education Week.

Susan Easton Black, an emeritus professor of Church history and doctrine, explained the tarring and feathering of Joseph Smith in a class Monday as part of BYU Education Week. (Trent Toone/Deseret News)

"I was asked to give some details on the life of Joseph Smith as it related to his experience of being tarred and feathered," Black said. "So my hope today is to teach you some new things. . . . I thought the room was pretty gloomy for a pretty gloomy topic, so we hope to brighten it up."

Joining and Leaving the Faith

Before discussing the violent event, Black explained some key events that led up to the tarring and feathering.

After arriving in Kirtland, Ohio, in the spring of 1831, Joseph Smith's wife, Emma, lost twins in childbirth. At the same time, another Latter-day Saint woman, the wife of John Murdock, died while giving birth to twins. John Murdock allowed the Smiths to raise his babies, Black said.

In May 1831, Joseph Smith was working on a translation of the Bible but progress was slow due to a large volume of visitors. During one visit, Joseph Smith used the priesthood to heal Elsa Johnson's arm, which resulted in the baptisms of Elsa Johnson, John Johnson, and a Methodist minister named Ezra Booth.

As a new member of the faith, Booth began preaching the gospel in Hiram, Ohio. In speaking to a Campbellite congregation, Booth was introduced to Symonds Ryder, who lived across the street from John Johnson.

Ryder excitedly went to Kirtland, met Joseph Smith, and was baptized. He asked the Prophet what the Lord wanted him to do. Go on a mission was the answer. Ryder requested a missionary certificate from the Prophet and Joseph mistakenly wrote "i's" instead of "y's," which didn't go over well with Ryder.

Ryder tore up the certificate and told Joseph if couldn't spell his name right he wasn't a prophet, Black said.

"I'm hard-pressed to say anything against the Prophet Joseph, but he really could have used a spell-check in this case," Black said, prompting laughter. "And the crazy thing is Symonds Ryder's name is still misspelled in the Doctrine and Covenants today. I'm sure the man just never gets over it."

A Plan to Stop the Saints

Time passed and John Johnson invited Joseph and Emma Smith to stay at his palatial home in Hiram, 30 miles from Kirtland, so he could focus more on the Bible translation. Sidney Rigdon joined them to help with the translation.

When Latter-day Saints learned that Joseph Smith had moved 30 miles away, some followed and asked John Johnson if they could build a log cabin or lean-to on his surrounding 350 acres of property, Black said.

"Now the result is, here is Symonds Ryder directly across the street," Black said. "It's kind of like living in Beverly Hills of their time period and as Symonds Ryder looks across the street, what does he see but shantytown."

Instead of bringing a welcome-to-the-neighborhood basket of goodies to the Smiths, Ryder began attacking Joseph and Sidney Rigdon via a local newspaper, Black said.

At the same time, rumors began to circulate that Hiram, Ohio, would be the new gathering place of the Saints, that the Johnson home would serve as Church headquarters, and that there were plans to build a temple in Hiram, Black said.

"So the question is how do you stop it? There were no laws at that time," Black said. "One way to stop it is to allow mobs to rule."

An Attempt to Murder the Prophet

Escaping from their outhouses, Black said a mob of 60 men assembled at the brickyard on March 24, 1832. They passed around a bucket of black paint and sang a song before heading for the John Johnson home, Black said.

Once there, 12 men burst through the door and moved in on Joseph. One man pulled Joseph's hair so hard that he pulled out part of his scalp. As another man grabbed his right leg, Joseph sent him sprawling out the door with a kick to the face. Even so, Joseph was manhandled and carried from the house.

Along the way to meet up with the larger group, Joseph saw Rigdon on the ground with a pool of blood around his head. He hit his head on ice as he was pulled from a shanty hut.

"You will spare my life, won't you?" Joseph Smith asked.

"Their comment is 'Call on your God for help for we will show you none,'" Black said.

Intending to kill him, Joseph was stripped of his clothing and taken to a Dr. Dennison, who was selected to castrate him, but his hand began to shake.

"In other words, could the doctor really do it? Apparently not," Black said.

Plan B was a vial of nitric acid. The doctor attempted to push it into his mouth but Joseph clenched his teeth, and in the struggle, Joseph's front tooth and the next one were chipped.

Now what? They reached for the tar bucket, which may have belonged to Ryder, Black said.

"Notice every time Joseph is incredibly hurt or struggles, who's leading the fight? It's always someone who at some point announced that he was a prophet but now turns his heel against the prophet," Black said.

Tarring has roots in 12th-century England where criminals were hanged, burned at the stake, or tarred. Tarring came to America with the pilgrims in 1620, Black said.

Typically, pine tar was heated and poured with a paddle down a person's throat where it formed a ball to suffocate the victim. If you wanted to mock the man and what he stood for, you pulled open a pillow case and feathered him, Black said.

"Very few people in the United States have been tarred and feathered," she said. "One was a prophet in 1832."

At that point, Joseph had no fight. He was tarred and feathered and appeared dead. Someone said the words, "The Mormons are coming," and the mob dispersed, Black said.

Joseph regained consciousness and removed the ball of tar from his mouth. He eventually made it back to the Johnson house where Emma saw him and fainted because she thought he was covered in blood, Black said.

Staying True to What We Believe

The Prophet's friends spent the night peeling off the tar off his body with cornhusker knives. The next day Joseph preached a sermon and baptized three people, Black said.

Rigdon recovered but likely had serious emotional and mental issues, Black said.

Sadly, 11-month-old baby boy Joseph Murdock died from exposure to the cold during the night, Black said.

"What can we learn from all this?" Black asked. "I think that what we learn is that those who enter baptismal waters, like Symonds Ryder, turned his heel against the prophet. If there's any message I want you to take is to stay true. . . . My husband and I, as we talk about the Church, we hear many people say, 'well I have questions now' and they are leaving. We find so many answers, we're staying. I trust and hope that will be the same with you."

Lead image by C.C.A. Christensen (1831-1912), which depicts the tarring and feathering of Joseph Smith. (Art by CCA Christensen, Provided by BYU Museum of Art)