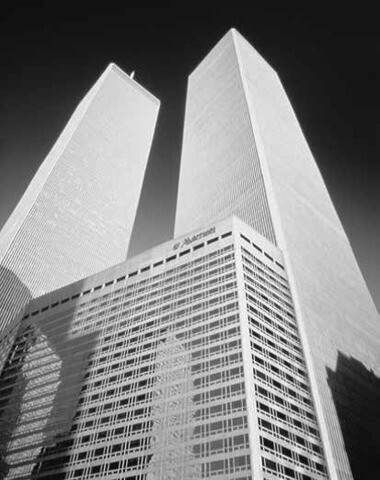

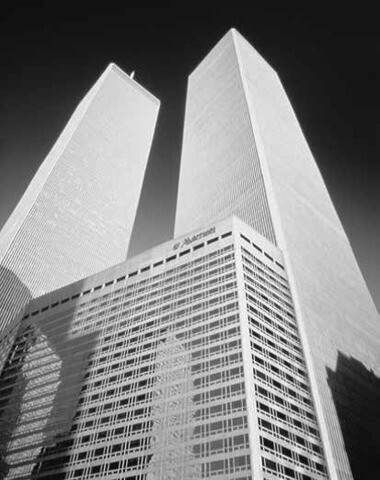

In 1991, Marriott opened the 37-story, 504-room Financial Center Marriott two blocks from the World Trade Center. It was the only competition for the nearby Vista International hotel, which was nestled between the massive 110-story Twin Towers of the World Trade Center.

Two years later, in February 1993, Islamic terrorists, attempting to bring down the Twin Towers, planted a bomb in the parking garage of Vista International. The explosion killed six people, injured 1,000 others, and caused major damage to the hotel. The power of the blast was felt at the nearby Financial Center Marriott.

Managers and associates of the Marriott rushed to help their Vista competitors, assigning space for a Vista command post and a place to hold press briefings. The Financial Center Marriott also provided complimentary housing for four days to 120 Port Authority officials and continuously delivered food to approximately 700 first responders and cleanup crews. The World Trade Center subsequently ran an ad in the New York Times proclaiming: “A million thanks, Marriott, for opening your doors to us.”

At that point, the Port Authority owned the Vista. After the bombing, it was renovated and reopened in 1994. Host Marriott bought it for $141.5 million in 1995 and renamed it the New York Marriott World Trade Center. Business mogul and Latter-day Saint Bill Marriott was thrilled with the acquisition and had no qualms about another terrorist attack. Since that location had been bombed before, security in the hotel was extensive.

No one ever imagined that a threat would come from above.

Terror Strikes

Bill drove to his Bethesda, Maryland, office early on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. It was a brilliant, blue-sky morning on the East Coast. He was feeling rested after two weeks at Lake Winnipesaukee and was booked on a noon flight for New York City, where he would attend a World Trade & Tourism Council executive committee meeting. A few minutes before 9 a.m., someone interrupted a meeting in his office to tell him that a plane had just struck one of the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers.

“I ran to the boardroom and turned on the big TV,” he recalled.

“The first images that came up showed billowing smoke and a gaping, fiery hole in one of the towers. My mind went straight to our guests and associates. Did the hotel team know what was going on? Were they already evacuating? Had anybody been hurt? The hotel’s associates were well trained for emergencies, but this emergency was like nothing we’d ever seen before.

“We tried frantically to get through to the hotel staff by telephone from the boardroom, to no avail. As the minutes went by, more people came into the boardroom where, like millions of other viewers, we were transfixed by those surreal images. Then we saw the second plane hit the other tower. Total silence in the room. We were all devastated. We kept trying to get through to our people. We had no idea how bad things were for them, but knew it must be pretty terrible. More than a few of us in that boardroom could not hold back the tears.”

Hijacked by terrorists and flying at 494 miles per hour, the American Airlines Flight 11 passenger jet had crashed into the north tower at 8:46 a.m. with a fiery explosion, sending debris crashing down to the streets. Part of the plane’s landing gear crashed through the roof of the 22-story Marriott below, landing in an office next to the pool and shaking the whole building.

The Evacuation

In the lobby, three Marriott associates gathered with walkie-talkies, as they had often practiced, to coordinate an evacuation—Rich Fetter, resident manager; Joe Keller, executive housekeeper; and Nancy Castillo, head of human resources for both the WTC Marriott and Financial Center Marriott. Several alarms were already sounding in the hotel, and the guest elevators automatically shut down. Unable to use the computers, Fetter found the last guest-list printout and gave it to Castillo for reference. He then dispatched associates to conduct a room-by-room check to make sure the guests were evacuating.

No one in the hotel could tell what had happened to the north tower because the gaping hole and fireball were not visible from any Marriott vantage point. But most of the guests knew enough to get out, using the stairs. However, Leigh Gilmore, a 42-year-old woman from Chicago with multiple sclerosis who was dependent on her motorized wheelchair, could do nothing but huddle with her mother in her fifth-floor room. Then a second plane, United Airlines Flight 175, struck the south tower at 9:03 a.m. Minutes later, two Marriott maintenance men found the Gilmores and rushed them onto a freight elevator to get them to safety.

By this time, the Marriott had also become an evacuation portal for those fleeing the Twin Towers through the door that connected the hotel to the north tower. Companies of firemen and Marriott staff directed more than 1,000 frightened people through the lobby to an exit onto Liberty Street. Debris and bodies were still dropping from above, so a policeman stood at the exit door to hold up the line sporadically when falling objects were spotted. Because of that corridor of safety, the Marriott hotel saved many lives.

A year later, the New York Times heralded this effort: “It was only a hotel, a 22-story dwarf tucked under colossal buildings, but in its final 102 minutes, the Marriott Hotel at 3 World Trade Center served as the mouth of a tunnel, a runway in and out of the burning towers for perhaps a thousand people or more [because] a cadre of unsung Marriott workers, from managers to porters, stayed behind to make sure their guests got out.”

One of those selfless heroes was audiovisual manager Abdu Malahi, who was last seen checking rooms for guests on the hotel’s upper floors; he died in the courageous effort.

In his 19th-floor room at the WTC Marriott, guest Frank Razzano thought he was safe. The Washington, D.C., lawyer assumed firemen would put out the high-level conflagration, and he thought he had plenty of time to leave the hotel. He showered, shaved, and packed his belongings and legal papers. He was about to call for a bellman to pick up his luggage when the south tower, after burning for 56 minutes, collapsed at 9:59 a.m., registering 2.1 on the Richter scale.

The 10-second collapse occurred inside a veil of smoke, so it appeared that the building simply imploded, falling straight down, but that was not the case. The top 30 or 40 floors broke off, pivoted, and fell eastward onto a neighboring office building. Other sections were propelled northwest toward Battery Park, while a few sections landed on the WTC Marriott, cleaving it in half. As this curtain of concrete and debris fell past his window, Razzano hugged the wall next to the door, certain that these were the last few moments of his life. Have I led a good life? Would my parents be proud of me? he wondered.

Moments before, in the lobby, Marriott associates were talking with each other and the firemen, pleased that the evacuation seemed to be nearly complete. Joe Keller had managed to reach his wife, Rose, and reassure her that he was just fine, but she urged him to leave. She recalled: “He told me that he was evacuating the people, and I selfishly said, ‘You get out.’ He said, ‘I’ll leave here when I can.’”

At the moment the tower fell onto the hotel, Keller was at the bellhop station talking to Rich Fetter, who was less than 15 feet away. The immediate pressure from the impact lifted everyone into the air and carried them through the lobby. Fetter was caught by a fireman, who pulled him to a column and hugged him close. “I flew from the middle of the lobby to the corner,” said Amy Ting. “I couldn’t see. All I could hear were things crashing—it was like death had just passed you by.”

When the remaining firemen’s flashlights flicked on, there was no sign of Keller or the other firemen behind a wall of debris. Reinforced beams installed in the hotel following the 1993 World Trade Center bombing had shielded a portion of the lobby from the crushing weight of the collapse. On-scene firefighter Patrick Carey said: “It was like the building was severed with scissors. If you were on one side of the line, you were okay. If you were on the other, you were lost.”

Keller was on the wrong side. But he was still alive.

Fetter managed to reach him on their walkie-talkies.

“I’m in an air pocket. I’m on a ledge. There’s a big hole, and I can see down to the lower levels of the hotel. Shouldn’t be able to do that. There’s two firemen in here with me and they seem to be hurt bad. I can’t get to them.” The firemen on the “safe” side of the lobby ordered the remaining trio of Marriott associates to evacuate immediately, and they began digging through the debris to rescue those on the other side.

Meanwhile, the same reinforced I-beams had saved not only Razzano but also, in the southern stairwell, 13 firemen led by Jeff Johnson of Engine Company 74. A single, narrow slice of the Marriott had survived. Razzano and the firemen found each other, and together they made an agonizingly slow 30-minute descent down the stairs over and around blocking debris. They were at the second floor when the north tower collapsed at 10:28 a.m. after burning for 102 minutes.

The rest of the Marriott hotel was crushed, as was everyone left inside, including Joe Keller.

Miraculously, the men in the southern stairwell, which was now crushed to about the third floor, were still alive. Recalled Razzano, “I heard what I can only describe as a freight train coming at me out of the sky, and then debris started to fall down on top of us.” Fireman Johnson remembered thinking, “Please don’t let me go like this. I’m too close.” All 14 subsequently made it out—the only people known to get out after the collapse of both towers.

Honoring the Fallen

Bill Marriott set up a crisis center at headquarters that was staffed around the clock in the first days after the attack. Flaming debris from one of the towers started a raging fire in the building next to the Marriott Financial Center hotel, so firemen used the hotel for more than a day as a staging area to fight the fire. Windows were broken, and there was water damage throughout the hotel, requiring its closure.

The loss of life was, of course, far more impactful. When an accounting was later taken, it appeared that at least 41 firefighters who had been trying to clear the WTC Marriott died when it was obliterated. Eleven of the 940 registered guests at the Marriott were unaccounted for and may have been among the numbers who died in the adjoining towers.

Within hours of the collapse, Bill called the families of Joe Keller and Abdu Malahi.

“I was deeply saddened by the loss of our men who, like their many colleagues that day, exhibited such bravery and dedication in the face of horrific tragedy,” he later wrote.

At the time, he told Fortune magazine: “This is the most difficult thing I’ve experienced in 45 years of business.”

On September 20, Bill was in New York to speak to his shell-shocked employees: “So many of you performed unbelievable acts of bravery in getting people to safety after the collapse of the towers—literally guiding people across steel girders that were all that was left of the lobby floor. Some of you remained at the hotel searching for coworkers and guests until firefighters forced you to leave when it was too dangerous to remain. I’ll never forget all you’ve done here. You’re all heroes in my eyes.”

Bill announced that all workers from the affected hotels would be covered by the company’s health insurance for a year. All of them would remain on the payroll until at least October 5. After that—because of the generosity of 1,500 Marriott associates donating more than $2 million of their vacation pay—all of them would be paid for a few months more. From his own family foundation, Bill wrote a $1 million grant to pay for survivor family expenses not covered by various federal and state emergency and relief organizations.

Five days after Christmas, a worker at Ground Zero found in the rubble the Marriott flag that had flown over the WTC Marriott. It was a bit burned, tattered, and torn. When it was delivered to Bill at headquarters, he said he would donate it to the projected 9/11 museum. In the meantime, he directed that it be displayed in a glass case in the lobby at headquarters so every visitor would see it when coming through the main door. Intended to honor the heroism of all Marriott associates, the plaque beside it read:

Our Spirit to Serve From sacrifice . . . honor From adversity . . . resolve From grief . . . remembrance

Images from Bill Marriott: Success Is Never Final

Bill Marriott, son of J. Williard Marriott who opened a root-beer stand that grew into the Hot Shoppes Restaurant chain and evolved into the Marriott hotel company, grew up in the family business. In his more than fifty years at the company’s helm, Bill Marriott was the driving force behind growing Marriott into the world’s largest global hotel chain.

Bill Marriott: Success Is Never Final gives readers an intimate portrait of the life of this business titan and his definition of success. Bill shares details about his private struggles with his father's chronic harsh criticism; his innovations in the hotel industry; and the boundless passion and energy he demonstrated for his work, family, and faith. Bill also shares spiritual experiences that allowed him to recognize God's guidance in his personal life.

This fascinating biography tells the story from Bill Marriott's first job in his family's restaurants to his monumental decisions in building a hotel empire. It is the remarkable story of a man who had the vision to create a multi-billion-dollar business, who understands the power of giving through substantial philanthropic work, and who lives the creed that hard work will pay off but success is never final.