Documents, Volume 11 of The Joseph Smith Papers covers a dynamic period in Joseph Smith’s life. At the outset of the volume, in September 1842, Joseph Smith was a hunted man and had to spend months in hiding avoiding arrest and extradition to Missouri. By February 1843, at the close of the volume, Joseph had experienced one of his greatest legal victories and was optimistically planning for additional growth and settlement in Nauvoo and the surrounding area. Throughout it all he remained energetically engaged in teaching the Saints and supporting the Church. Here are five surprising things we learn about Joseph Smith and Nauvoo in this volume of The Joseph Smith Papers.

1. Joseph Smith received help from a surprising group of individuals.

In May 1842, an unknown assailant shot former Missouri governor Lilburn W. Boggs. Though lacking any evidence, Missouri and Illinois officials sought to extradite Joseph Smith and Orrin Porter Rockwell to stand trial for supposedly planning and carrying out the assassination attempt. Because of these charges, Joseph spent much of the summer, fall, and winter of 1842 in hiding. During this time, many Latter-day Saints helped to hide or keep Joseph safe, but he also received help from a number of surprising individuals.

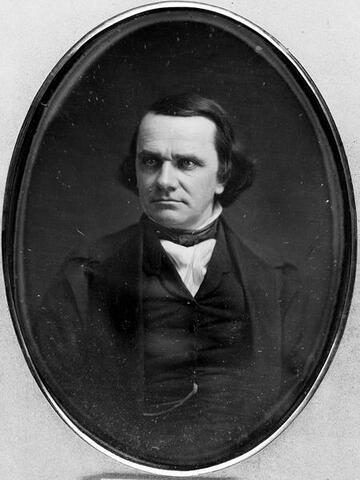

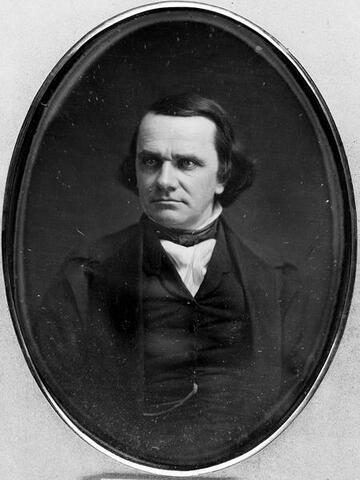

John F. BoyntonOn September 3, 1842, law officers surprised Joseph at his home while he was eating with his family. However, former apostle John F. Boynton delayed the officers at the front door while Joseph ran out the back to safety. Though he had left the Church in 1837, Boynton moved to Nauvoo in 1840 and remained a close friend of the Prophet. Another time, in the Illinois state capital, Joseph received legal counsel and guidance from politicians Stephen A. Douglas, then a state supreme court justice, and recently elected Illinois governor Thomas Ford. Although Ford later had a much more complicated relationship with Joseph and the Saints, in 1842, he was one of Joseph’s closet political allies.[1]

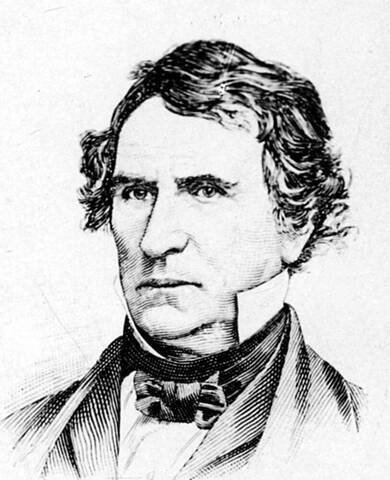

2. Joseph Smith was freed by a federal court.

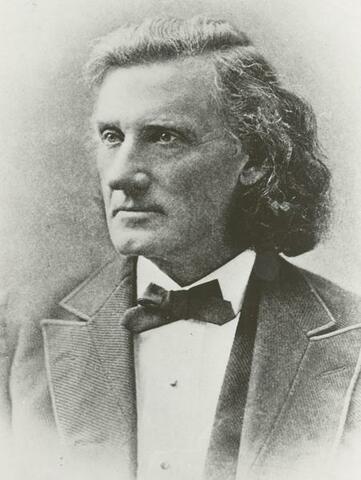

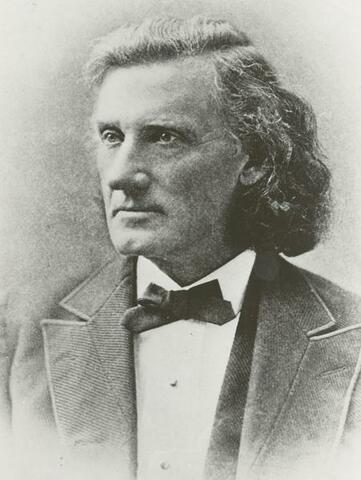

Stephen DouglasActing on the advice of Ford, Douglas, and his own attorney, Joseph allowed himself to be arrested on December 26, 1842, and traveled with a group of close friends to Springfield, Illinois, for a prearranged habeas corpus hearing before federal judge Nathaniel Pope in the United States Circuit Court for the District of Illinois. Habeas corpus is a legal measure that allowed courts to review the legitimacy of an arrest or imprisonment without addressing the guilt or innocence of the prisoner.

Joseph’s arrival in the state capital caused considerable excitement, and many residents and politicians wanted a chance to meet the Prophet. His hearing was held on January 4, 1843, in the federal courtroom across the street from the state capitol building.[2] Many people crowded the courtroom, and several women—including the recently married Mary Todd Lincoln—were allowed to enter the room and witness the proceedings from Judge Pope’s bench. Joseph’s attorney, Justin Butterfield, made the most of this unique setting in his opening remarks, which became legendary among Illinois attorneys: “I rise under the most extraordinary circumstances in this age and country, religious as it is! I appear before the Pope, supported on either hand by Angels, to defend the Prophet of the Lord!”[3]

Justin Butterfield, courtesy Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library & Museum, Springfield, IL. On January 5, Pope ruled that the documentation supporting Missouri’s extradition request was deficient and not enough to justify Joseph Smith’s extradition, freeing the Prophet from the threat of arrest. Although Pope’s ruling did not address the question of Joseph’s guilt or innocence, it was one of the most significant legal victories of Joseph’s life. When Joseph returned to Nauvoo, he was greeted with parties and well-wishers. Some of his friends, such as Willard Richards, Wilson Law, and Eliza R. Snow, even wrote songs celebrating the ruling and the roles Ford, Butterfield, and Pope had played in Joseph’s victory.[4]

3. Joseph Smith had Doctrine and Covenants section 76 rewritten as a poem.

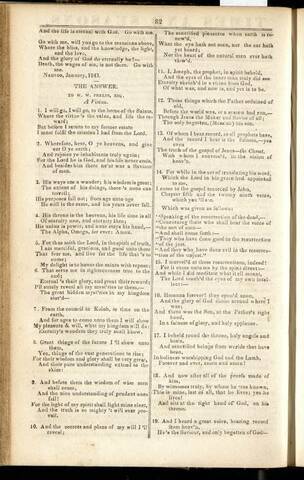

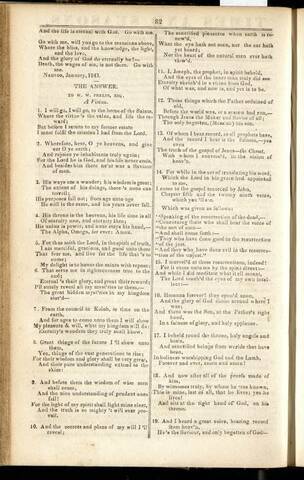

One version of Doctrine and Covenants 76 written in poem form, to W. W. PhelpsDuring Joseph Smith’s January 1843 legal hearing in Springfield, his attorney remarked that the only difference between Joseph and biblical prophets was that the “old prop[h]ets prophicid in Poet[r]y & the modern in Prose.”[5] In an apparent attempt to eliminate this distinction, sometime in February 1843, Joseph had his 1832 vision, now recorded as section 76 of the Doctrine and Covenants, adapted into a poem. In general, the poem closely followed the text of the vision in the Doctrine and Covenants, but it did contain additional language about revelations Joseph had received since 1832, such as baptism for the dead and teachings from the Book of Abraham. We do not know how closely Joseph was involved with writing the poem, however, and he may have just assigned one of his scribes, such as William W. Phelps, to write it.[6]

4. Tithing was not always money in the 1840s.

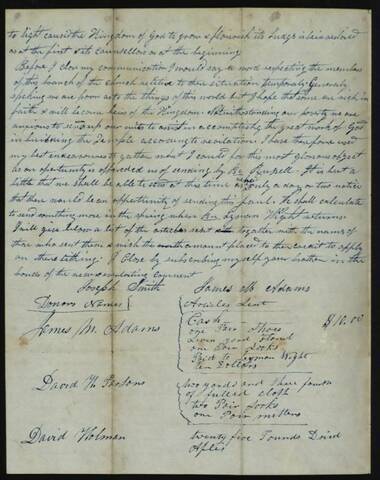

All throughout Documents, Volume 11, the Saints continued laboring and sacrificing to build the Nauvoo Temple. The temple was to be funded by tithing, and by 1842, the Church had developed a system that is very different from what Latter-day Saints practice today. Most of the Saints in Nauvoo were very poor and had nothing to contribute to building the temple but their time. Accordingly, very early on, the Church adopted a system of labor tithing, where men in Nauvoo worked one day in every ten on the temple. Every year the men in the city would account for their labor with the temple recorder, and if they had worked 31 days (one-tenth the number of days in the year minus Sundays) they would receive a certificate from Joseph Smith’s clerks giving them access to the temple baptismal font to perform baptisms for the dead and other ordinances—an early form of a temple recommend.[7]

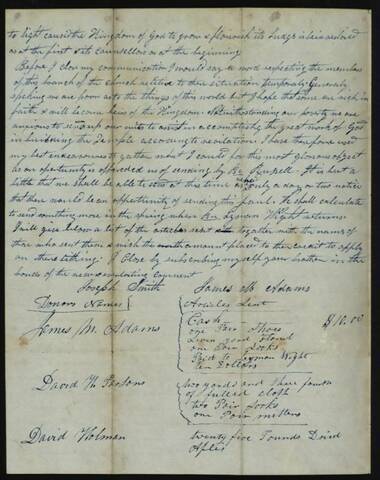

Page of a letter from John A. Adams describing his and other Ohio Church members' donations Other Saints who lived farther away from Nauvoo were expected to donate generously to build the temple, but gathering supplies and bringing that tithing to Nauvoo brought serious challenges. In November 1842, a Church member from Nauvoo passed through Andover, Ohio, while on personal business. The branch there hurried to gather up what tithing they could on short notice to send back with him for the temple. While the branch managed to gather $30 of currency, most of the tithing collected consisted of goods the Saints in Andover could spare, such as six pairs of socks, three pairs of shoes, two pairs of mittens, over a dozen yards of fabric, yarn, leather, a quilt, two handkerchiefs, and 25 pounds of dried apples.[8] Throughout the fall and winter of 1842, Joseph was actively working to ensure that the tithing was appropriately used and distributed.[9]

5. Joseph Smith tried to establish other Latter-day Saint cities outside of Nauvoo.

In February 1843, Joseph Smith and other Church leaders were excited about their prospects in Illinois. Believing that the threat of extradition and persecution from Missouri had ceased, Church leaders sought to build up Nauvoo and find other gathering places for the Saints. Around this same time, a dishonest land speculator named John Cowan convinced Joseph to travel about 30 miles north to visit a small settlement on the Mississippi River named Shokokon. There, Cowan and other locals flattered Joseph and expressed an interest in the Church and convinced him that the struggling town would make a perfect location for a Latter-day Saint settlement. On February 20, 1843, Joseph purchased 39 town lots and sent several families there to settle under the direction of Amasa Lyman. Unfortunately, while the settlement had appeared promising in the winter, with the arrival of spring and summer it became clear that Shokokon was, in the words of Brigham Young, “a perfect swamp” and the settlement was soon abandoned.[10]

All photos courtesy of The Joseph Smith Papers unless otherwise indicated.

Learn more in The Joseph Smith Papers, Documents, Vol. 11: September 1842–February 1843, available at Deseret Book stores and on deseretbook.com.

Notes:

[1] Letter from Thomas Ford, 17 Dec. 1842, JSP, D11:278–282; Letter from Justin Butterfield, 17 Dec. 1842, JSP, D11:282–285.

[2] Petition to the United States Circuit Court for the District of Illinois, 31 Dec. 1842, JSP, D11:310–312.

[3] “Rich!” Ottawa Free Trader, 13 Jan. 1843. Decades later, attorney Isaac Arnold published a more fleshed out account of Butterfield’s remarks, claiming that Butterfield, dressed in his finest coat and vest, “rose with dignity” and opened his remarks by saying, “May it please the Court, I appear before you to day under circumstances most novel and peculiar. I am to address the ‘Pope’ (bowing to the Judge) surrounded by angels, (bowing still lower to the ladies), in the presence of the holy Apostles, in behalf of the Prophet of the Lord.” Arnold, Reminiscences of the Illinois Bar Forty Years Ago, 6.

[4] Jubilee Songs, between 11 and 18 Jan. 1843, JSP, D11:335–344.

[5] Joseph Smith, Journal, 4 Jan. 1843, in JSP, J2:224.

[6] Poem to William W. Phelps, between circa 1 and circa 15 Feb. 1843, JSP, D11:421–435.

[7] Authorization for Shadrack Roundy, 24 Nov. 1842, JSP, D11: 229–231.

[8] Letter from James M. Adams, 16 Nov. 1842, JSP, D11: 224–229.

[9] Notice, 11 Oct. 1842, JSP, D11:148–150; Letter to “Hands in the Stone Shop,” 21 Dec. 1842, JSP, D11:295–298.

[10] Minutes, 10 Feb. 1843, JSP, D11:411–413; Deed from Robert and Mary McQueen, 20 Feb. 1843, JSP, D11:447–452; Power of Attorney to Amasa Lyman, 28 Feb. 1843, JSP, 479–483.