In honor of the 175th anniversary of the martyrdom of the Prophet Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum, LDS Living is sharing a series of articles about early Church history. The following article originally ran on LDS Living in June 2016.

As early as 1843, the Prophet Joseph Smith was aware of plots to have him silenced, whether by placing him back in jail or killing him.

In September 1843, Joseph Smith was shown a copy of a letter from Samuel Owens of Independence, Missouri, and wrote in his journal, “To show the wickedness and rascality of John C. Bennett and the corrupt conspiracy formed against me in Missouri and Illinois, I insert the following under date of the letter. (June 10, 1843)” (Joseph Smith, History of the Church Vol. 5 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 1978), 422). According to the letter, Owens, who was determined to have the prophet arrested on false charges and returned to Missouri, had been in contact with people such as John Bennett, Governor Reynolds, Governor Ford, Harmon Wilson of Carthage, Illinois, and Joseph Reynolds of Missouri. But these weren’t the only men involved. After further research, it has been verified, the “corrupt conspiracy” discovered by Joseph Smith included many other enemies of the Church, who conspired together to plan the martyrdom and force the exodus of the Saints. Enemies of the Church became desperate, wanting their illegal acts kept secret even while they plotted to kidnap Joseph. But after several unsuccessful kidnapping attempts, they determined to murder the prophet instead.

However, the reasons for killing the Prophet go far beyond a hatred of the Church and its beliefs. Here are just a few of those intriguing insights behind the plot to murder Joseph Smith.

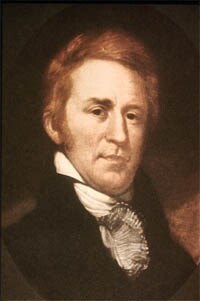

1.William Clark, formerly of the Lewis and Clark expedition, and the Chouteau family were afraid that if Latter-day Saints moved to Missouri, it would upset some dishonest business deals Clark and the Chouteaus relied on.

Portrait of William Clark

Shortly after the Church was officially organized, Oliver Cowdery wrote to U.S. Superintendent of Indian Affairs William Clark on February 14, 1831, seeking permission to teach the Native Americans in Kansas Territory, near Jackson County, Missouri. Clark didn’t respond to Cowdery’s request, and the missionaries were forced to leave.

As a result of the 1830 Indian Relocation Act, many Indian tribes were forced to remove to Kansas and Oklahoma Territories. During that time, Clark, Senator Thomas Benton (former Chairman of the Senate Committee of Indian Affairs), and Pierre Chouteau and certain members of his family were associated together in what their local newspaper identified as the “Little Junto” (or “St. Louis Junto”).

Often, Chouteau family members, as federal Indian Agents, would negotiate treaty terms with tribal leaders and secure large annual government annuities to pay for the Native Americans’ relocation, with approval from Clark and Benton. The Native Americans would in turn purchase goods at inflated prices at the various Chouteau family trading posts using these government funds, funneling large amounts of money into the pockets of the Chouteaus, Clark, and Benton.

As Latter-day Saint communities continued to expand in Missouri, members of the St. Louis Junto continued to fear the Saints would return to Jackson County and challenge their trade monopoly. On May 12, 1836, Francois Chouteau of Jackson County wrote to his uncle Pierre Menard, “Apparently we are going to wage war here very soon with the Mormons. They have a force of 2000 men in Clay County who are organizing and making the arrangements necessary to attack us in Jackson County… It appears that they are disposed to retake possession of their land by force… we are determined to fight to the end rather than consent that the Mormons remain here” (Dorothy Brandt Marra, Cher Oncle, Cher Papa (Kansas City: University of Missouri, Western Historical Manuscript Collection, 2001) 154). Even after the Saints settled in Nauvoo, St. Louis Junto members still feared the Latter-day Saints might return as Joseph Smith was eagerly pursuing the various Redress Petitions in Congress for reparations and the right to return to their lands in Missouri.

2. Local Independence merchants felt threatened by the gathering Saints.

The first sale of lots in the new town of Independence, Missouri, occurred in July 1827. Of the initial public sale of 75 lots, a group of merchants formed a coalition and purchased more than one-third of them. Lilburn Boggs and Samuel Owens were early leaders of the “Independence Merchants,” many of whom were involved in the Santa Fe and Indian trade.

A few years later, however, Sydney Gilbert was called to operate the bishop’s storehouse in Independence. Because the storehouse operated under the newly-introduced law of consecration, many of the goods sold in Gilbert’s store were provided at no cost by faithful members. But when the store began trading with Santa Fe merchants and local farmers, the other Independence merchants couldn’t compete. Evidence of the merchants’ resentment of the store surfaced when the Saints were forced out of Jackson County in 1834, and most of the destruction from the mobs was aimed at the Gilbert store and the William Phelps printing office.

The harassment didn’t end there, however. Samuel Owens continued persecuting the Saints for more than 10 years and was connected with other conspirator groups through family relationships. For example, Owens' wife was a cousin to Senator Richard Young, who later served as the judge when Joseph's murderers were acquitted. Like the “Little Junto” group, Samuel Owens and the other Independence merchants also were concerned that Joseph Smith might prevail with the Redress Petitions to Congress in 1843-1844 and return to challenge their trade dominance in the Jackson County region.

3.Warsaw, Illinois, officials worried that their city would be bypassed by a new waterway while the Latter-day Saints in Nauvoo, Montrose, and Keokuk would have ready access to it.

Lt. Robert E. Lee (later of Civil War fame), working for the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers, was assigned to clear the Des Moines Rapids on the Mississippi River between Commerce (Nauvoo) and Warsaw. In 1837, after many surveys, Lee discovered what he called the “Spanish Chute” underneath the surface of the Rapids, which he felt could be cleared to provide year-round steamboat access. Unfortunately for the Warsaw land speculators and residents, this natural waterway went from Nashville to Keokuk. Nauvoo, Montrose, and Keokuk would benefit from Lee’s efforts, but Warsaw would likely be left out. Furthermore, Lee later sold a steamboat to Joseph Smith and other Church members shortly after the Latter-day Saints arrived in Nauvoo, making Warsaw land speculators even more angry and covetous of the resources the Latter-day Saints had.

4.The arrival of the Saints in Nauvoo interrupted plans for a railroad project.

Before the Saints arrived in 1839, the Illinois State Legislature approved the creation of the Des Moines Rapids Railroad to be built from Commerce (Nauvoo) to Warsaw, Illinois.

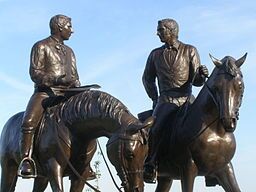

Statue of Joseph and Hyrum's ride to Carthage, found in front of the Nauvoo Illinois Temple

The Des Moines Rapids Railroad was planned to run directly through Nauvoo to the Nauvoo steamboat landing sites. Cranes would unload cargo directly from the docked steamboats at Nauvoo to the railroad cars and then run to Warsaw to be reloaded back to steamboats during annual low water periods. Under this plan, Warsaw could remain a key commercial trade center with Nauvoo, but the newly arriving Latter-day Saints were settling right in the way of the planned railroad route.

Enemies of the Church privately suggested a solution by having the Latter-day Saints improve the area and then forcing them to leave so the land could be reclaimed and the railroad completed.

5. Involved in the plot to murder Joseph Smith were nine commissioners directly associated with the planned railroads for Hancock County.

These included Mark Aldrich of Warsaw, a former state legislator and a commissioner of the Warsaw Peoria Wabash Railroad and Des Moines Rapids Railroad a partner with other commissioners including former Governor Joe Duncan in the Warsaw Land Company. Aldrich was a major in the militia and charged as one of the five defendants in Joseph’s and Hyrum’s murder.

6.The New York Land Company wanted the 20,000 acres of Latter-day Saint-owned lands in Iowa.

Map of the Half Breed Tract in Iowa

In 1841, Francis Scott Key (author of the United States national anthem) visited Nauvoo and the Iowa Territory as an attorney for the New York Land Company (Sina Dubovoy, The Lost World Of Francis Scott Key (Bloomington, IN: WestBow Press, 2014)). While in Iowa, Key proposed a plan to aid the Iowa courts in partitioning the entire 119,000 acres of the Iowa Half Breed Tract lands. The New York Land Company used Key’s plan to secure more than 41 percent of the 119,000 acres and discretely and dishonestly reclaimed the 20,000+ acres purchased by Vinson Knight and Joseph Smith from Isaac Galland in 1839.

The Plat Map of Nashville, Iowa, preserved in the Church History Museum, shows these New York Land Company lots in Nashville in 1841 and court documents confirm all the other lands in Nashville and in the rest of the Half Breed Tract were transferred to the other petitioners, disenfranchising all 20,000 acres held by the Latter-day Saints. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld this partition agreement, which occurred in October 1841 (Clagett v. Kilbourne U.S. Supreme Court, No. 238 (Reprint) settled in 1861).

New York Land Company leaders and other claimants were anxious to take away these lands and force the Saints out of Iowa so they could pursue their own developments. David Kilbourne, a known enemy to the Church, was the local agent for the New York Land Company. Kilbourne assisted various apostate members of the Church who were involved in the Nauvoo Expositor anti-Church newspaper.

Image of the first copy of the Nauvoo Expositor

Research suggests that representatives of these various groups, including the St. Louis Junto, the Independence merchants, the New York Land Company, and the Illinois railroad commissioners were linked to the final plans to murder the prophet. Each of these groups had greedy economic reasons they wanted the Latter-day Saints to leave, and the only way they thought they could succeed was by killing the Prophet Joseph.

Images from Wikimedia Commons

For more great insights like these, check out Mark Goodmansen’s book Conspiracy at Carthage: The Plot to Murder Joseph Smith, available at Deseret Book stores or deseretbook.com. For more information, check out markgoodmansen.com.